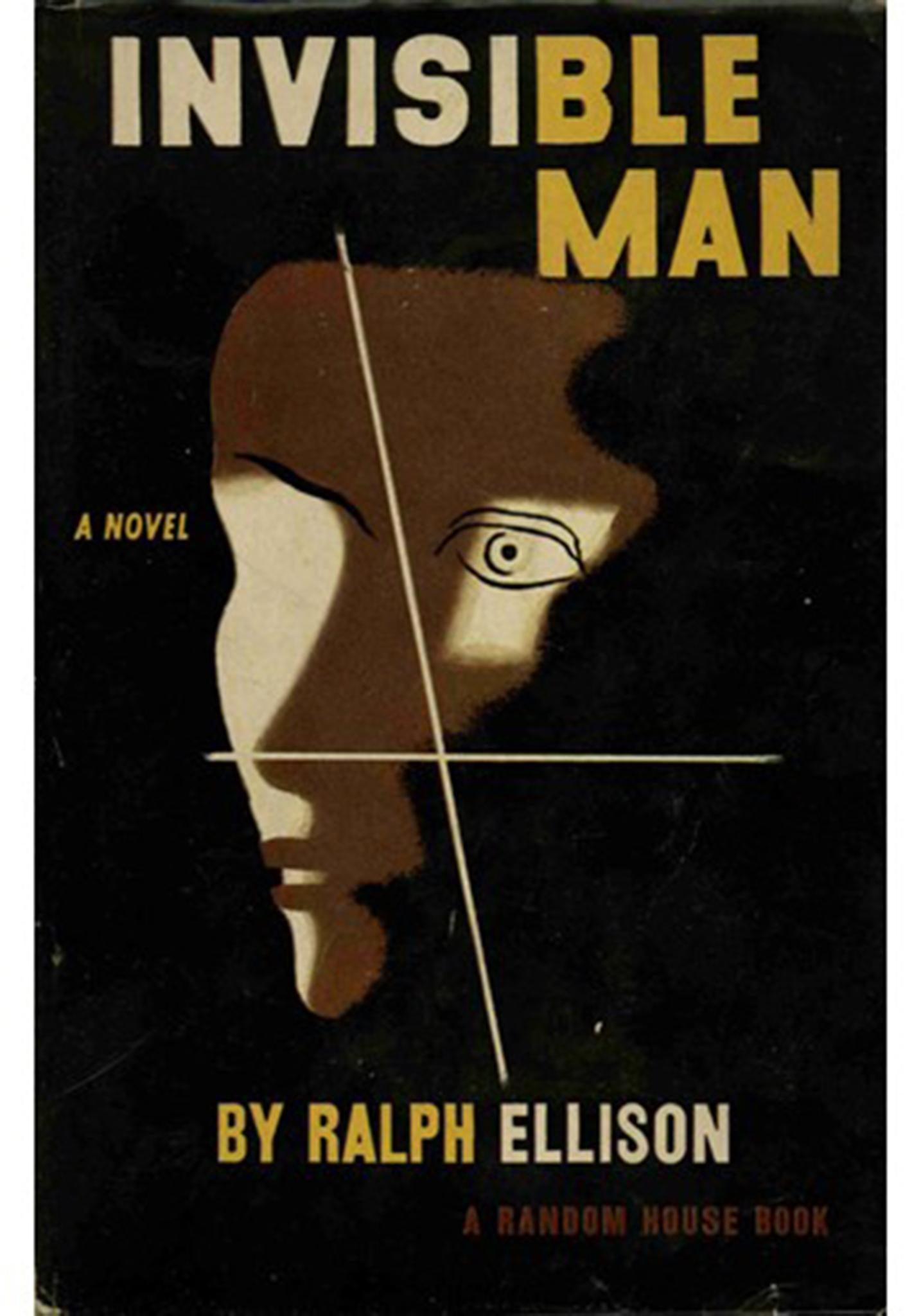

Book of a Lifetime by Paul Gambaccini - Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

'No author working today should try to write The Great American Novel. It has already been written. It is Invisible Man'

No author working today should try to write The Great American Novel. It has already been written. It is Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. Or, if one wishes to factor in public affection and popular success, it is To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee. The point is, no book can claim to be The Great American Novel if it does not address the most important of all American subjects, race relations.

I was a Martin Luther King kid. I was 13 years old in 1962 when one of my fellow students in Civics class brought in a copy of the 16-page comic book Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. I can’t remember which, but the pupil was either Carol Klein or the improbably-named Candy Land. (Yes, readers, she really was a sweet girl.)

I was surprised by my ignorance. How could a year-long bus boycott have happened in my own country without my knowing about it? True, I could be forgiven for not being on top of world affairs when I was eight years old, but that merely meant that I had a lot of catching up to do. I started reading the important books in what was then called Negro literature. Foremost among these was invisible man, published in 1952 and winner of the National Book Award for Fiction the following year.

Invisible Man shares with a tale of two cities the distinction of having indisputably great first and last lines. “I am an invisible man,” the first sentence states simply. It is then qualified: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.”

It is a literary way of saying “They all look the same to me”. White people do not discern the narrator simply because he is black, in the same way that many young people do not register the presence of old men and women they pass in the street. Being different leads to being ignored.

The specific subject matter is of Ellison’s time. He concerns himself with topics from jazz to contemporary politics. But appreciating this novel does not require expertise on either of these subjects, any more than readers of Moby Dick need to be familiar with the specifics of whaling. We learn of racism across America, from the segregated South to the streets of Harlem, all experienced by a narrator whose adventures are as wide-ranging as those of Candide or Odysseus.

The ending is both everyday and fantastic. The narrator comes to rest in the shut-off basement of a New York apartment building rented to whites only, lit by 1,369 bulbs illuminated by electricity siphoned off from Monopolated Light and Power. He relates his story and listens to his beloved Louis Armstrong. Finally, having told his tale, he is ready to live again above ground, no less invisible but aware of his social responsibility. It is a symbolic ending to a book rich in symbolism.

Oh, yes. I mentioned the last line. There has not been a month in my life when I have not thought of it. The message from downstairs reminds us that circumstances may be individual but humanity is universal: “Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?”

‘Love, Paul Gambaccini:My Year Under the Yewtree’, is published by Biteback

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks