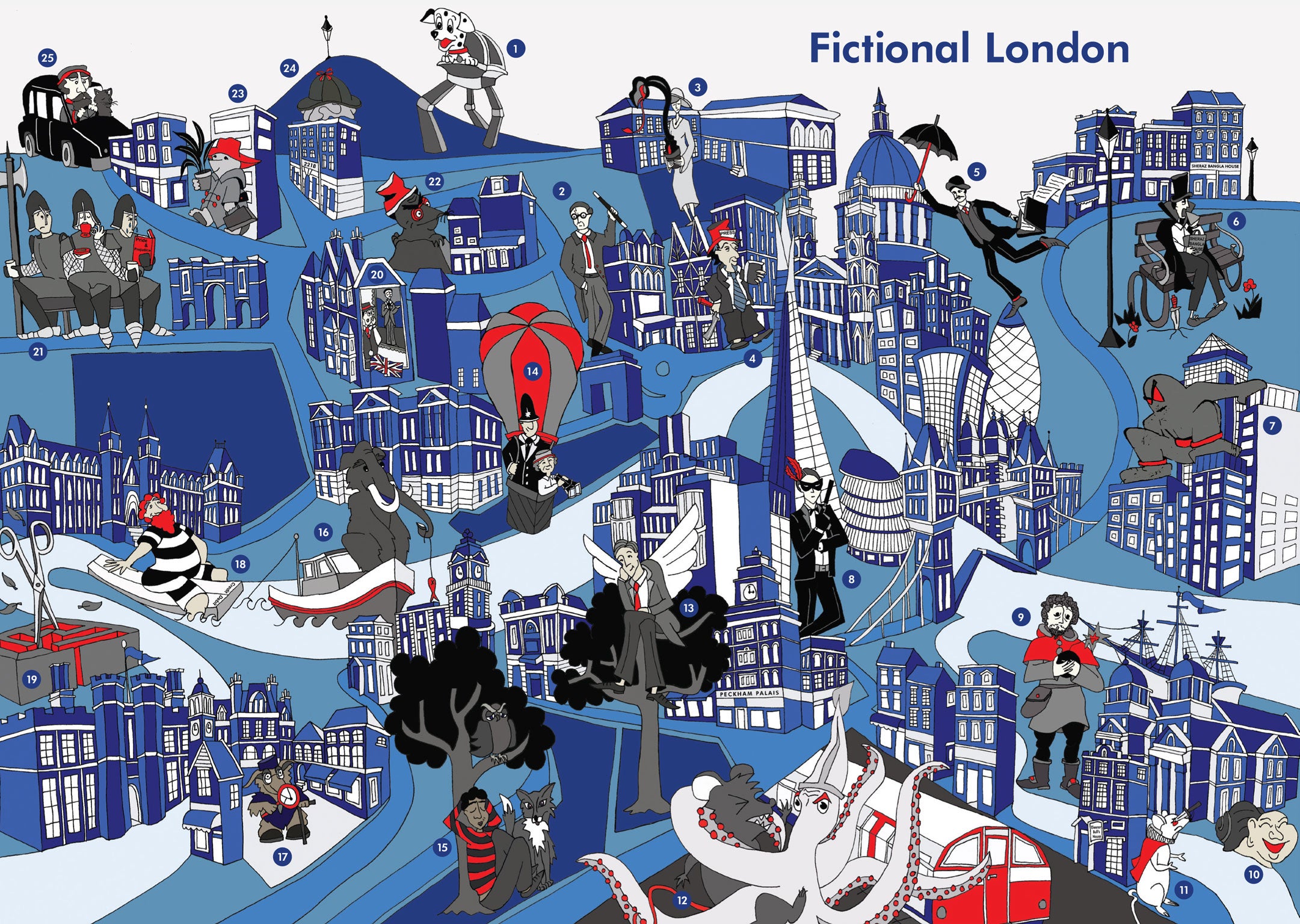

A literary London mash-up map

What happens when Sweeney Todd gets friendly with Lord Copper?

Mrs Dalloway decided to buy a couple of the Triffid guns and went out into the garden of Russell Square.” [3] ‘Mrs Dalloway’, Virginia Woolf (1925) and ‘The Day of the Triffids’, John Wyndham (1951). Mapping fictional London could be an overwhelming task. London inspires literature in staggering volumes, more than anywhere else in the world. Walking through central London, your imagination might easily bump into Clarissa Dalloway, Bridget Jones and Mary Poppins, not to mention Sherlock Holmes, the Artful Dodger or Adrian Mole. For centuries writers have been steering their creations through London, which is now almost as crowded with iconic characters and stories as it is with real people.

“No, no, no,” said Venus fretfully. “I was down at the water-side, looking for a woolly mammoth on the banks of the Thames.” [16] ‘Our Mutual Friend’, Charles Dickens (1864-5) and ‘Tanglewreck’, Jeanette Winterson (2006). We produce Curiocity, a map-magazine that looks at London in unusual ways. With each themed, lettered issue we’re creating an alternative A to Z of the capital, and “Fictional London” seemed to be the obvious angle for Issue F. There have been many previous attempts to map London’s literature, from comprehensive street-by-street indexes to graphic artworks and wiki websites. Finding a new way to approach it could be tricky. The art of mapping is deciding what to omit, chipping away and smoothing corners until you’re left with something that navigates a complex terrain. Working with the map artist Lucie Conoley, we’ve cut through swathes of literature and selected what we feel is a representative range of fiction set in the capital.

“They found hanging upon the wall a splendid portrait of their master and could see that, if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.” [20] ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’, Oscar Wilde (1890) and ‘The Code of the Woosters’, P G Wodehouse (1938). We began by reflecting on the ways in which we encounter London as readers, and quickly noticed that the abiding, and sometimes only, impression we had of many areas in London was that which we had experienced first through books. Who, for instance, can think about one mainline railway station without visualising a hairy little fellow with marmalade sandwiches, or another without conjuring up images of school scarves and broomsticks? Stories shape our experience of the city, and do much to create the mental pictures we carry around with us. As Will Self said about exploring Paris, the experience was inextricably “framed by the fictive”. Fiction is the second life of a city and has a profound effect on the way it is experienced by visitors and its inhabitants.

“What did surprise the Dearlys was the way Pongo and Missis paused, rigid, to hear if the Martian had thrust its tentacles through the opening.” [1] ‘The Hundred and One Dalmatians’, Dodie Smith (1956) and ‘The War of the Worlds’, H G Wells (1897). These mental maps of real places that literature creates are not an original discovery, but the intriguing thing about navigating somewhere as thickly populated with stories as London is that we become adept at holding multiple, separate versions of the city in our mind. We wouldn’t usually let the dog’s-eye-view of London in The Hundred and One Dalmatians, for instance, interact with the post-apocalyptic, weed-infested wasteland of The War of the Worlds, and yet the Twilight Bark and the Martians’ final stand both take place at the top of Primrose Hill. Our mind’s eye splits the screen, but just imagine what would happen if those worlds were combined. Our map collapses the layers of the palimpsest and brings different texts into conversation with one another. We’ve introduced Bertie Wooster to Dorian Gray, for example, and Sweeney Todd to Scoop’s Lord Copper.

“I’m not a criminal,” said Paddington, hotly. “I’m colourless, spectacled, and intensely disagreeable.” [23] ‘A Bear Called Paddington’, Michael Bond (1958) and ‘Keep the Aspidistra Flying’, George Orwell (1936). For each pairing, we’ve stitched together a new Frankenstein quotation using a short line from each book. The results have led to the revelation of Adrian Mole’s evil streak, the introduction of a mammoth to 19th-century London, and the release of Bungo the Womble’s inner beast. Some London fictions aim to record the city accurately, while others transform it. Combining different styles led to some bizarre concoctions, which read a little like a post-modern scrying technique. Perhaps if these new quotations are divined correctly they will reveal deep insights into the reality of the city …

“Dougal posed like an angel-devil, with his hump shoulder and bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars.” [13] ‘The Ballad of Peckham Rye’, Muriel Spark (1960) and ‘The Life of William Blake’, Alexander Gilchrist (1863). Certainly these mash-ups invite a fresh way of looking at London literature and the city itself, and that is the purpose of Curiocity: to reimagine the city in thought-provoking ways. Our previous issues have included a zoo map of London animals, a star chart of the city at night and an urban anatomy drawn as a dissected body. It feels appropriate to be celebrating London’s printed heritage with this issue, because the magazine itself is a celebration of what can seem an increasingly anachronistic medium. When we decided to go into print in 2011, we knew we wanted to create something tactile that would offer an experience you simply couldn’t have on a screen. With maps and articles weaving unpredictably across its folds, Curiocity requires real physical engagement. In fact sometimes you even need to fold it in a certain way to read an article.

“The handsomest of all the Wombles was a bit of a thug on the side, always running up against the law.” [17] ‘The Wombles’, Elisabeth Beresford (1968) and ‘The Light of Day’, Graham Swift (2003). The process of conceiving and designing this map has shown us how powerful London’s fiction can be. In the most extreme cases, fiction has even created feedback loops, with Sherlock Holmes’s rooms appearing on Baker Street, a luggage trolley becoming stuck fast on its way to Platform 9¾ and Peter Pan playing his pipes in Kensington Gardens. These overt realisations of fiction serve as a reminder that the line between reality and fiction is always blurred. As Patrick Keiller the film maker said, “more than with any other capital, you can make your own London.” We all narrate our own stories, which filter our experience and render one person’s impression of London totally different to another’s. In this map we have fictionalised London fictions, and come up with something that hopefully captures the spirit of the eight million fictional Londons alive in the city today.

Issue F of ‘Curiocity’ will be published on 8 February. You can get your copy in bookshops across London or pre-order on the website: www.curiocity.org.uk. Lucie Conoley can be contacted through her website: www.lucieconoley.com.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks