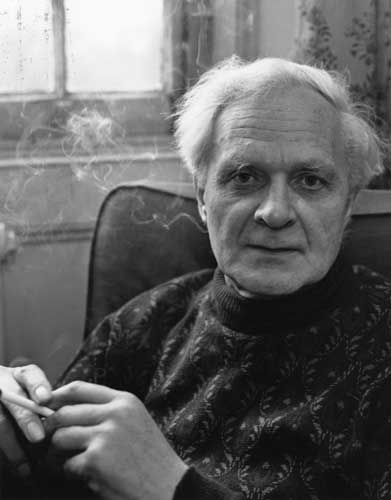

Angel of the Left: Paul Binding recalls his friendship with Stephen Spender

It's 100 years since the birth of Stephen Spender, the eminent writer, socialist, and companion of Auden and Isherwood. Paul Binding recalls a treasured friendship with the Grand Old Man of poetry, who remained humble to the end

The poet Stephen Spender was born on 28 February 1909, making this his centenary year, although commemorating it feels strange, for he was youthful and responsive to life to the last. I was lucky enough to get to know him in his old age and it seems a fitting moment to reflect on his work and legacy. As one who spent his early childhood in war-devastated Germany, I was drawn to Spender's work, especially his Forties poems and European Witness (1946), his travelogue of his return to the country which had once given him so much. But I also admired his works of cultural criticism, The Creative Element (1953) and The Struggle of the Modern (1963). I thought he confronted situations others had evaded or preferred to treat in isolation, presenting them with haunting verbal music (the poems) or analytic precision (the prose).

"History has tongues / Has angels has guns" he proclaimed in "Exiles from their Land, History their Domicile", a poem in his 1939 collection The Still Centre. The young poet had witnessed the victory of Nazism in Germany and Austria and been a campaigner on behalf of the Republic during the Spanish Civil War. Written while guns were proving frighteningly triumphant in the Western world, its lines celebrate "freedom's friends", those who were working away to produce literature, scientific discoveries, political programmes, and who were frequently the butt of mockery for their eccentricity or unworldliness. History will, the poem states, vindicate them, for ultimately goodness triumphs.

An almost compulsive reviser of his poems, even ones already published and well-received, Spender rewrote this one several times. The version in his Collected Poems of 1955 is particularly impressive in its conclusion. The poet begs recall from "this exile" (the contemporary political world), "And let my words appear / A heaven-printed world."

During the Second World War, Spender produced an interesting short book, Life and the Poet. In a still trenchant passage he declared: "One of the most pregnant sayings of all time is that the Sabbath is made for Man and not Man for the Sabbath ... The poet and the great scientist are fully aware that in itself the Sabbath – even the newest Sabbath – is but a shell. What is important is Man. The creative mind must never entirely subscribe to any kind of Sabbath – Pharisaic, Jewish, Christian, Roman, Communist or British Imperialist."

To an important degree Spender's whole life's work was an attempt to oppose sabbaths wherever they were imposed – from his early apostrophes to the democratic spirit ("Oh young men Oh young comrades / it is too late now to stay in your houses / your fathers built where they built you to breed / money on money") to his tireless later work for Index on Censorship, founded in 1972, to assist writers exiled in their own lands; "freedom's friends", stifled or silenced in totalitarian regimes.

Those exiles toiling in penury remained a part of Spender's imagination throughout his writing career, however far he may outwardly have seemed to have journeyed from them. In 1965, Spender, who was a regular academic visitor to America, was made the Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the United States Library of Congress, the first non-American to be honoured. From 1970-77 he was Professor of English at University College London; in 1983 he was knighted. But both in poetry and prose he never ceased to honour the individual's private vision and the paramount duty of society to ensure, for every single member, its preservation.

The Second World War was, as his moving and ingeniously constructed autobiography, World Within World attests, a watershed for him. Spender was reared in London but was a quarter-German, a quarter-German Jewish on his mother's side, and after Oxford he chose to immerse himself in German life and culture. In this he enjoyed the companionship of two other seekers, his older contemporaries and mentors, WH Auden and Christopher Isherwood; his relationship with them has tended to obscure his own achievement. In Hamburg in 1929, on his first excursion to Germany, Spender bought himself a little pocket-book containing Rilke's Duineser Elegien (Duino Elegies). Ten years later, collaborating with the Oxford scholar JB Leishman, he produced the seminal and still unsurpassed English rendering of this mighty poem sequence.

Spender came on his father's side from a family of eminent liberal journalists, so it was inevitable that he took a serious, active interest in contemporary politics. Depression England, Germany and Austria "after the failure of banks", and riven Spain, elicited some of his most sensitive, acute and best-known poems, such as "Two Armies" and "Ultima Ratio Regum". The bewildering confusions of the exterior world were matched by confusions in the poet's emotional and sexual life, which found expression in some of this period's most heartfelt poems: "For T A R H", dedicated to a male lover, and "The Little Coat" about his first wife, Inez ("The little coat embroidered with birds / Is irretrievably ruined/... I leaned my head against her breast / And all the birds seemed to sing/ While I listened to that one heavy bird/ Thudding at the centre of our happiness."

He was back in England for the war, a period in which he co-founded and co-edited the distinguished magazine Horizon, married the pianist Natasha Litvin, fathered a son and joined the fire service. Not just his life but his art underwent a palpable change, and became – for all the originality and excellence of the pre-war work – profounder. A rediscovery of his own London roots took place, encouraging identification with generations past and present of his native city. "Epilogue to a Human Drama" and "Rejoice in the Abyss" pay literary homage to the bombed capital because of their complete fusion of the poet's individuality with his apprehension of the society all around him. "London burned with unsentimental dignity / Of resigned kingship" he says in the first, where he depicts Londoners re-enacting Shakespearean drama. In the latter, commemorating a walk after an air-raid, he has the sensation that "The streets were filled with London prophets, / Saints of Covent Garden, Parliament Hill Fields, / Hampstead Heath, Lambeth and Saint John's Wood Churchyard ..."

It was in the war, too, that his realisation of the saving nature of the arts, fortified by his prodigious reading and empathic relationship to painting and music, made him dedicate himself to their furtherance. These endeavours had to be linked to the question asked by all thinking persons once hostilities ended and the extent of European suffering was revealed: "However did such terrible things come about?"

A letter I wrote to him began a friendship of nearly 20 years. In this centenary year, I find myself mentally returning to my very first visit, in November 1977, to the duck-egg blue villa in St John's Wood where he and Natasha made their home and where they were, countless times, to receive me. I'd come to ask him about two poems which fascinated me: "The Angel", with its echoes of Rilke, and "The War God". I found myself in the presence of a handsome man, so tall that Auden had ascribed his height to his wish to reach Heaven, and notably gentle and courteous in speech.

I had not then realised the painful – and quite unwarranted – diffidence that Spender felt towards his own productions. He was forthcoming about the genesis of "The Angel". He had felt that, every so often, another person says and does things unique to and wholly appropriate for the individual moment, thus becoming one's "angel". About the poem itself he was far warier. "It could end on each stanza, couldn't it?" he observed sadly. I thought he was wrong, but was too diffident myself to defend it. Then we came to "The War God" (in its first version). "Why cannot the one good / Benevolent feasible / Final dove descend?" the poem asks.

It was late afternoon, and Spender was sitting away from any lamp. "Can you remind me please of the poem's last lines?" he asked me. So I read aloud the half-tragic, half-affirmative answer to the poem's initial question: "For the world is the world / And not the slain / Nor the slayer, forgive, / Nor do wild shores / Of passionate histories / Close on endless love; / Though hidden under seas / Of chafing despair, / Love's need does not cease."

"That is rather good, isn't it?" he said, the only time in two decades I ever heard him express anything like satisfaction with what he had written.

Spender's interest in politics never abated, and always he eschewed the morally simplified stance. But he was unequivocal about what he thought the truly humane course in any issue should be. A late article stressed the importance to British children of immigrant origin of reading matter reflecting their own lives. To the end, he was a spokesperson for a "heaven-printed world".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments