I love graphic novels. I read lots of them. I'm collaborating with an artist to write one. I make sure we stock as many as we can in Review, the independent bookshop in Peckham, south London, where I work. But the ones I love most aren't "novels" at all. Of course, I've enjoyed the fictional worlds of Alan Moore, Daniel Clowes and Charles Burns; and Chris Ware is one of the most brilliant storytellers working in any medium, but for me, it is graphic non-fiction with which I've had the most intense relationship.

There is something that I think is uniquely interesting about the genre – it offers a space to explore "real" life in a way nothing else quite does. As anyone who has read Art Spiegelman's seminal classic Maus, or Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis, or any of Joe Sacco's work will know, something miraculous occurs when those boxes with pictures and words encounter the weightiest of subjects.

The first graphic memoir I ever read was called Dragonslippers: This is what an Abusive Relationship Looks Like by Rosalind B Penfold. Here, the way Penfold frames her images, and uses the grammar of the comic strip, does more to bring home the message that abuse can, and does, exist within relationships that appear "normal" from the outside than anything I'd ever read before, or since.

Penfold's simple line drawings that evoke the work of the late American cartoonist, Charles M Schulz, of Peanuts fame, are able to communicate the disjunction between innocence and abuse with startling power.

Perhaps there is something about the connection to the comic form that we associate with childishness, with artlessness and with certain sorts of safety, which means that it has become the perfect form for exploring personal and historic pain. I challenge anyone to read Ethel and Ernest, the story of Raymond Briggs' parents – from their first meeting to their deaths – and not be moved, not just by the subject matter but by its intersection with form. You can feel the care, the love, the reverence, with which he tells their stories. It's not for nothing that emerging writers are told to show and not tell.

There is something about the frame of the graphic novel that feels less obviously rhetorical than writing alone – it is as if we are free from the author's head, and are an extra set of eyes on the past. It's no coincidence that so many of the greatest recent graphic memoirs have involved authors going back into their childhood and telling the story of their families. Fun Home and Are you my Mother? by Alison Bechdel, Epileptic by David B. and Blankets by Craig Thompson all take us back into that semi-mythologised space of the author's childhood and find something that transcends the biographical and anecdotal.

One of my favourite graphic memoirs, Stitches, by David Small, tells the story of the author from the age of six to adulthood, and that of his parents. His mother, who was born with her heart on the wrong side of her chest, and his grandmother, who goes insane, locks her husband in their house and sets fire to it while she dances around the yard naked. But this is back story – the real story revolves around the fact that after hundreds of x-rays, given by Small's father, a surgeon, to try to treat his son's sinus problems, Small develops a lump in his neck. His mother – a closet lesbian, dealing with her disappointment in how her life has panned out with a silent fury – is reluctant to have the lump looked at because of the cost. The lump grows, and Small's parents go on a shopping spree, buying a new car, furs, hosting lavish parties.

When Small eventually has surgery some years later, the lump turns out to be cancer. On waking up from the operation that finally removes it, he can no longer speak. The fact that it was cancer is kept from him, until he finds an unfinished letter written by his mother, telling someone else "of course, the boy does not know it was cancer." That he is able to survive this, forgive his parents and find a voice to tell his story is truly wonderful.

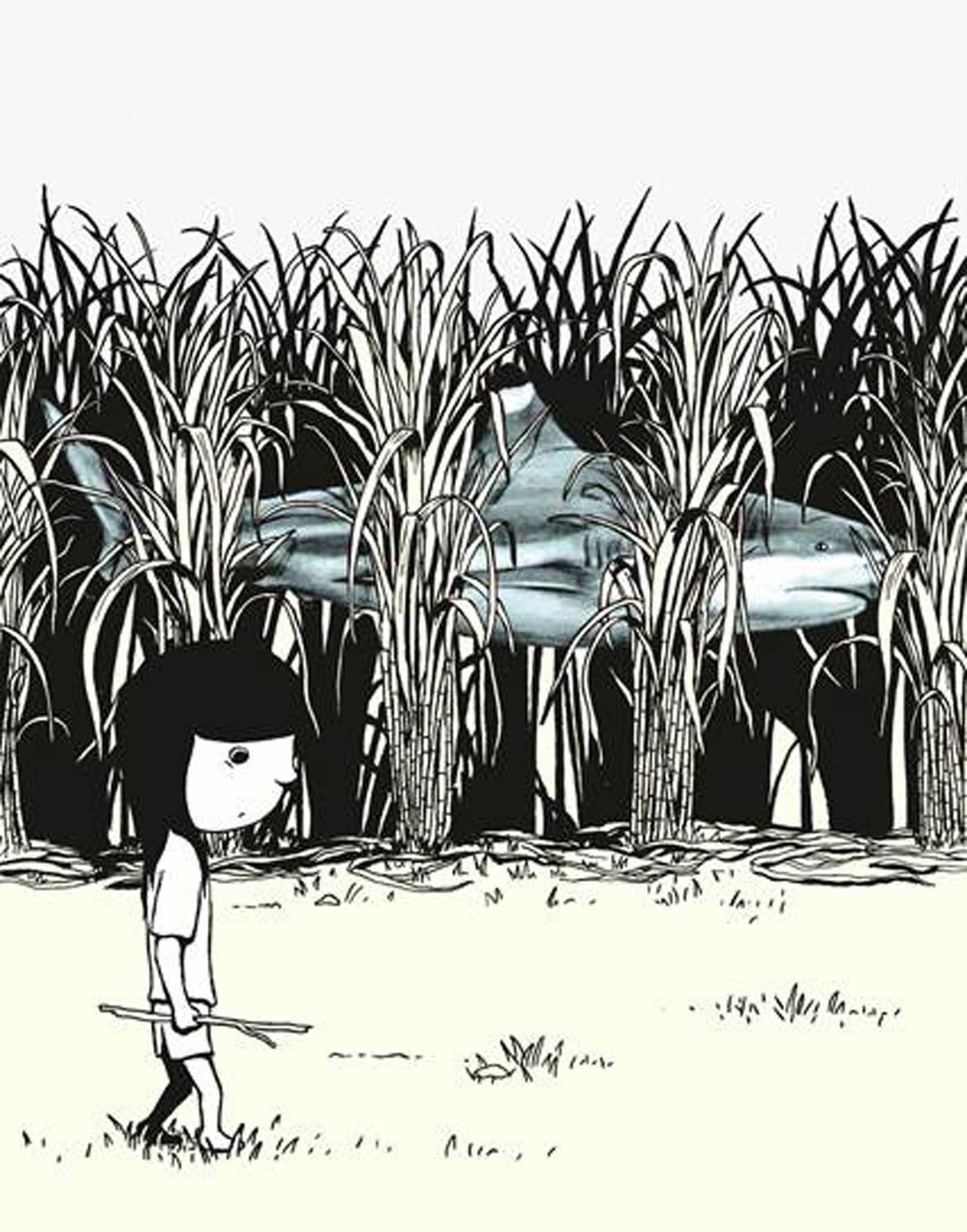

I collaborated with Joseph Sumner to produce a graphic memoir, because I wanted to look at some parts of my life with that same distance. They are moments, none as dramatic as the ones in Small's life, that I don't understand in any way other than visual. Rodney Fox, I Love You is about childhood between Australia and south London, shark phobia, my family, and specifically my father who I witnessed but didn't understand, and also his death which is something I shy away from in writing. Being able to give these stories over to someone else to interpret felt like another layer. When Joseph returned the images to me, after we'd talked in quite an abstract way about what they should be like, I could see patterns that I wasn't aware of before, but that seemed to fit in to place when drawn.

What graphic novels do for me is work in conversation with a reader's expectations and use them to find new ways of telling stories. I would put Chris Ware's Building Stories up against anything published in the past five years for sheer imaginative ambition and scope – it makes much else of what novelists are doing seem childish in comparison.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments