For your Christmas list: The best fiction and non-fiction books of 2025

Captivating novels, surprising memoirs and tales of deception are to the fore as the year draws to a close and our chief book critic Martin Chilton picks his best 2025 reads

Narrowing down the best books of 2025 to a list of 15 inevitably means leaving out fine works, including Shadow Ticket, the first novel by Thomas Pynchon in 12 years, and We Do Not Part by Nobel Prize in Literature winner Han Kang.

The year marked what would have been Jane Austen’s 250th birthday, and following the example of her Pride and Prejudice character Caroline Bingley, who said, “I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading”, I have selected books that were, in the main, simply a joy to read.

The final pick includes a captivating novel by Sarah Hall, David Szalay’s Booker Prize-winner, sparkling debut fiction by Charlotte Runcie and Florence Knapp, powerful literary memoirs of Muriel Spark and Gertrude Stein and surprising, engaging memoirs from women as diverse as Kathy Burke and Arundhati Roy.

15. Wild Cities: Discovering New Ways of Living in the Modern Urban Jungle by Chris Fitch (William Collins)

It has been another excellent year for nature and environmental non-fiction books – including Harriet Rix’s The Genius of Trees, a profoundly inventive exploration of the science of trees – and the one I single out is Chris Fitch’s study of what pioneering cities around the world are doing to fight a seemingly losing battle against vanishing nature. Wild Cities: Discovering New Ways of Living in the Modern Urban Jungle does not sugarcoat the problems but explains in illuminating detail, through investigation and personal anecdotes, the undeniable benefits of nature. A truly uplifting read.

14. Exterminate/Regenerate: The Story of Doctor Who by John Higgs (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Doctor Who has been on our television screens since November 1963. Although I am not an ardent fan of the programme, I was very taken with John Higgs’s “biography of the infamous Time Lord”. As well as being a study of the famous science fiction character, Exterminate/Regenerate: The Story of Doctor Who also offers telling insights into British society and the failings of the BBC. There are shocking accounts of bad-tempered, homophobic, heavy-drinking, sexist actors and corporate bigwigs in the mix of a book that is also crammed with fascinating nuggets about the Doctor Who villains.

13. Mother Mary Comes To Me by Arundhati Roy (Hamish Hamilton)

Arundhati Roy, author of the masterpiece novel The God of Small Things, was born in northeast India in 1961. She had a disturbing, unusual childhood. The story of her abrasive and abusive mother – along with her drunken, absent father – is at the core of a memoir that also includes her film and book work and her time as a “writer-activist”. Mother Mary Comes To Me is a funny, candid and perceptive memoir.

12. Good Anger: How Rethinking Rage Can Change Our Lives by Sam Parker (Bloomsbury)

In a year in which stress, sadness and toxic anger seem to be endemic around the globe, Sam Parker’s Good Anger: How Rethinking Rage Can Change Our Lives is a timely and powerfully engaging account of the author’s own battle to understand the benefits of “good anger”. Drawing on insights from psychology, philosophy and emotional science, Parker, a senior editor at British GQ, explores why “leaning into anger” can be a way to find mental peace and a healthy perspective. A perceptive, thoughtful book.

11. A Mind of My Own by Kathy Burke (Simon and Schuster)

I enjoyed several “celebrity” memoirs this year – including those by Margaret Atwood, Bill Gates, Cat Stevens and Patti Smith – but the quirkiest and most endearing was by the actor and director Kathy Burke. The Londoner, famous for her television characters Waynetta Slob and the teenage oik Perry, writes startling and moving tales in an evocative, witty way. Burke is also refreshingly blunt about the unpleasant people she has encountered in the course of the fame game.

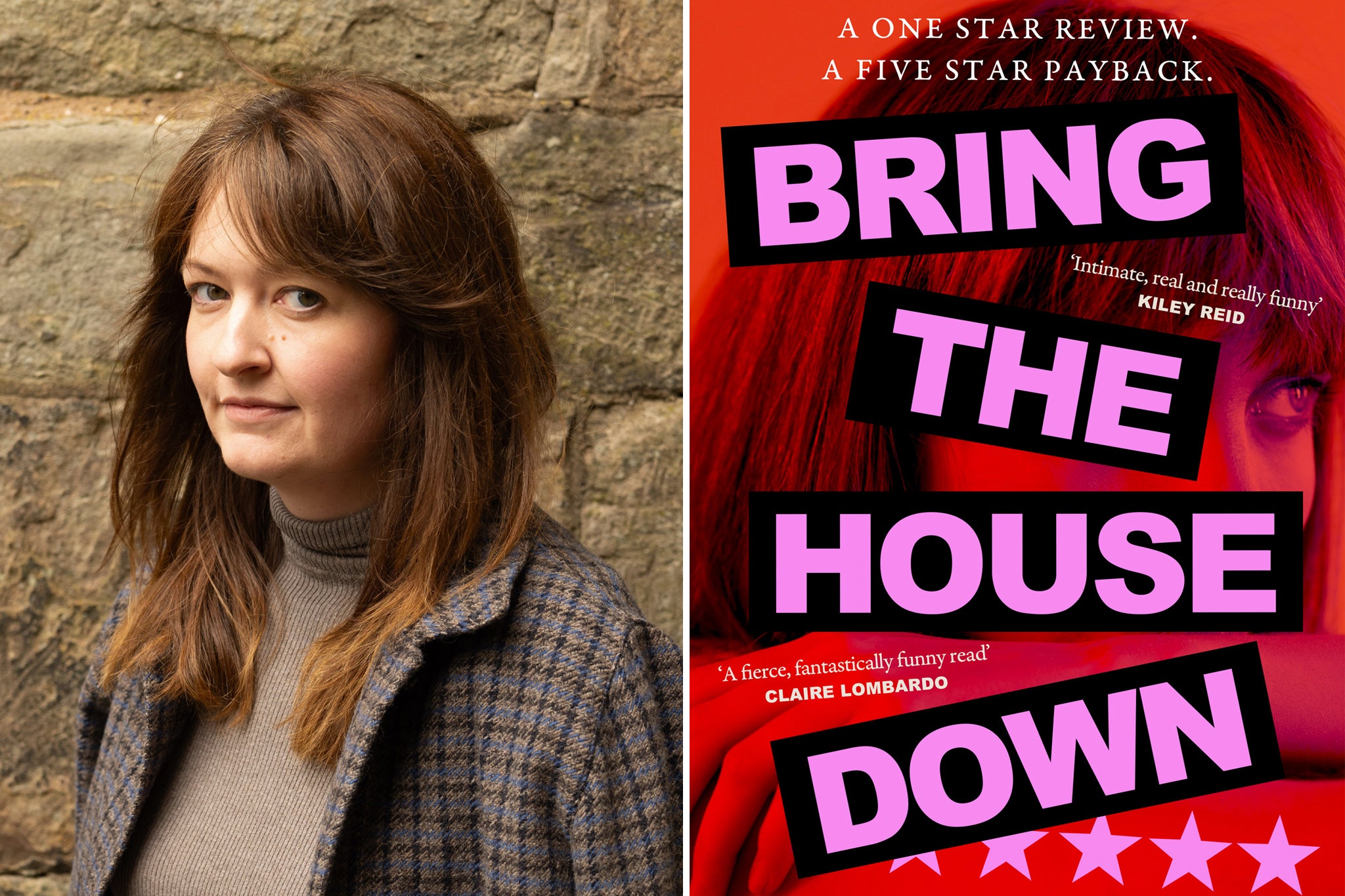

10. Bringing The House Down by Charlotte Runcie (The Borough Press)

Taking place at the Edinburgh Festival, this novel offers a sharp, canny and amusing portrait of arts journalism as it compassionately skewers a successful, slightly vicious newspaper critic who becomes embroiled in a scandal. Runcie’s stunning debut in fiction is full of powerful central characters (including the young female comedian mistreated by the critic) set amid a consuming drama of modern meltdown. A haunting story of betrayal.

9. Electric Spark: The Enigma of Muriel Spark by Frances Wilson (Bloomsbury Circus)

Frances Wilson’s excellent Electric Spark: The Enigma of Muriel Spark focuses on the early years of the author of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Spark, born in Edinburgh in 1918, had an eventful life – full of bitter splits, bad relationships, espionage, poverty and mental health problems – and the biographer skilfully weaves together numerous intriguing strands to flesh out this portrait of a truly enigmatic writer.

8. Audition by Katie Kitamura (Fern Press)

The Booker-shortlisted Audition begins with an accomplished actor preparing for an upcoming premiere and meeting a mysterious, attractive young man in a Manhattan restaurant. In Part one we are shown one path for the actor and her husband, Tomas. Part two offers a very different life arc for her, a competing narrative that is deeply unsettling for the reader. We are all caught in a game of performance and role-playing, Katie Kitamura seems to suggest. Part of the appeal is a protagonist who is the embodiment of the unreliable narrator. Audition, which sparkles with honed sentences, offers a forceful and bleak view of our performative age.

7. Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife by Francesca Wade (Faber)

Gertrude Stein, the Godmother of literary modernism, is a true curiosity. Some people rave about her work; others castigate her writing. She certainly seemed to want abject adulation from everyone around. While Francesca Wade may dub Stein a “megalomaniac”, the biographer offers a balanced, fascinating account of her qualities, alongside the flaws. Wade also benefits from being the first researcher to examine the rich archive of Stein material collected by the late researcher Leon Katz. Wade provides a treasure trove of incidental details in this superb, well-researched book.

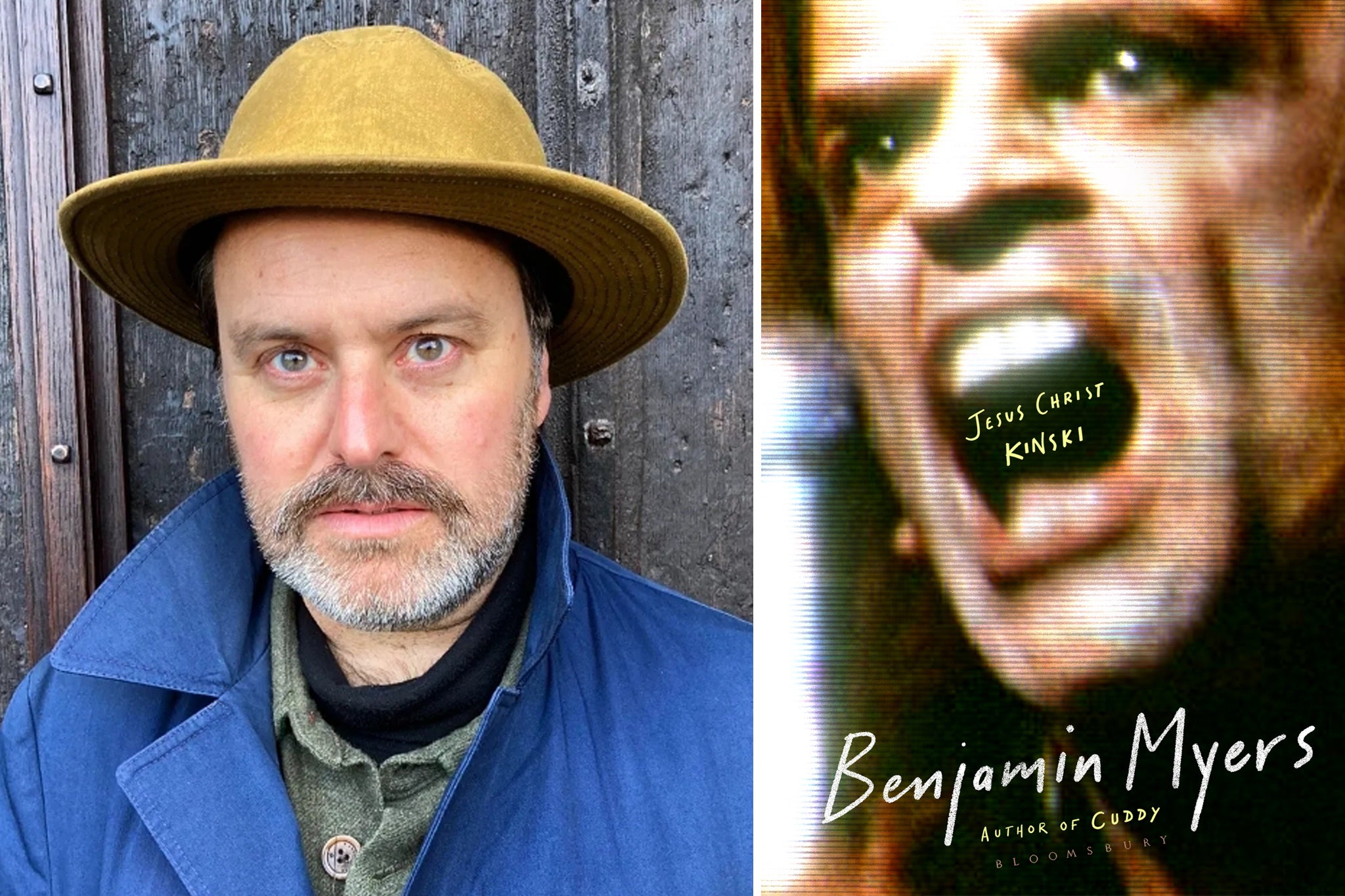

6. Jesus Christ Kinski: A Novel about a Film about a Performance about Jesus by Benjamin Myers (Bloomsbury Circus)

I had high regard for the thought-provoking Twist by Colum McCann and the entertaining The Rest of Our Lives by Ben Markovits, but they were edged out in the final pick here by Benjamin Myers’s tale of a housebound writer who becomes obsessed with the late German actor Klaus Kinski. This spellbinding novel centres around a one-man show Kinski delivered in Berlin in November 1971 about Jesus (“mankind’s most exciting story”), a performance that ended in uproar. The bold, inventive structure of Jesus Christ Kinski gives Myers the room to reflect on stagecraft, censorship, mental health, loneliness, cancel culture – and what we do with great art made by horrible people.

5. Flesh by David Szalay (Jonathan Cape)

David Szalay’s Flesh, a novel that explores contemporary masculinity through the eventful life of Hungarian protagonist István, was the “unanimous” choice as winner of the 2025 Booker Prize. Szalay’s novel, which encompasses teenage sex, infidelity, murder, death and war alongside everyday struggle, is written in prose that is pared to the bone. His sparse style allows the story’s darkness and understated complexity to gradually take a grip on your imagination. It is the way Szalay brings such an introverted protagonist to life that makes the book so hypnotic.

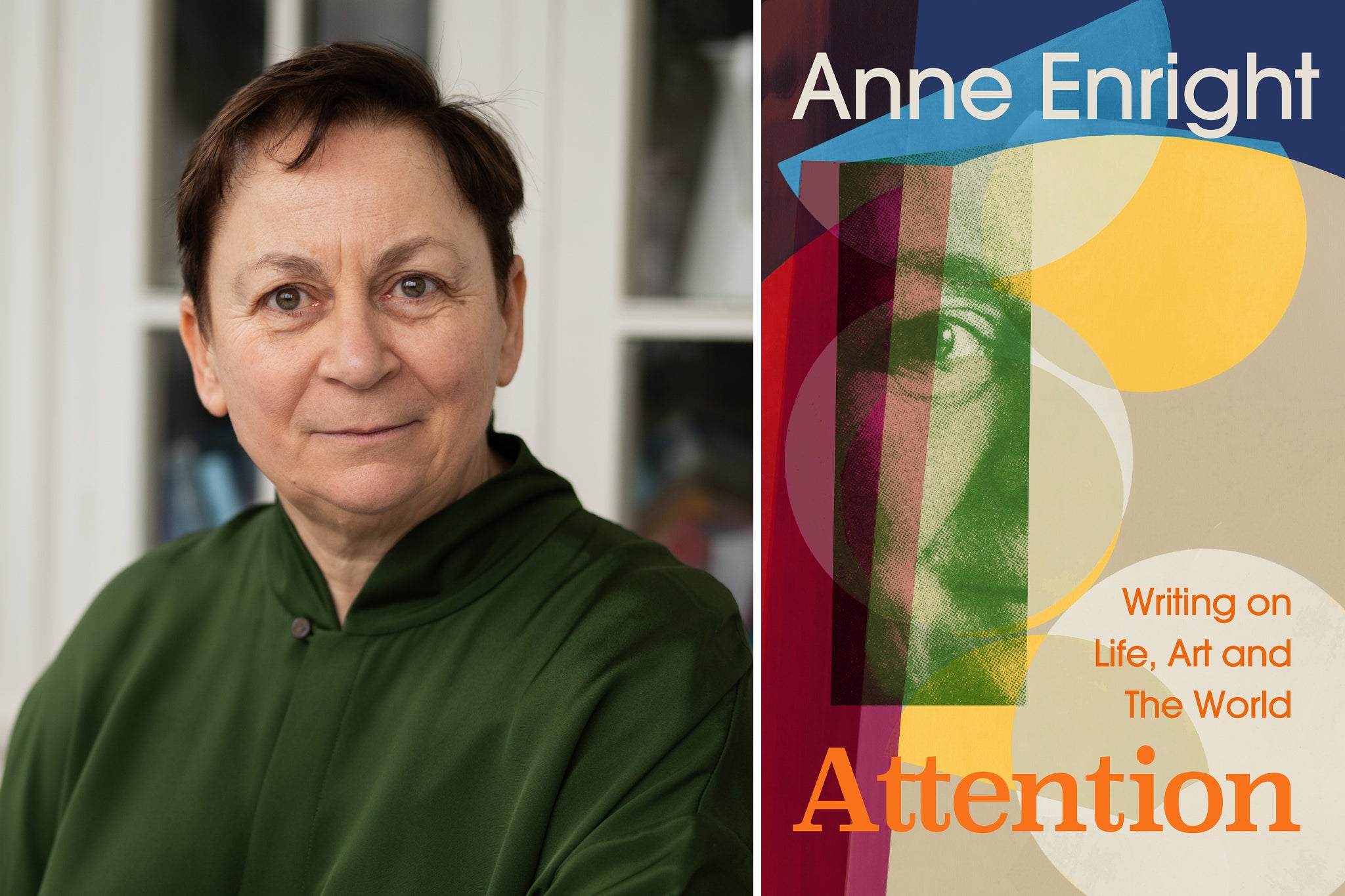

4. Attention: Writing on Life, Art and the World by Anne Enright (Vintage)

It was hard to select my favourite essays of 2025 – there were strong offerings from Zadie Smith (Dead and Alive), Andrew O’Hagan (On Friendship) and Philippa Snow (It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame) – although the standout publication was Attention: Writing on Life, Art and the World, which brings together Anne Enright’s wide-ranging cultural criticism, literary and autobiographical prose for the first time. I am a big fan of Enright’s fiction: Attention confirms the intelligence, compassion and humour of the mind behind the novels.

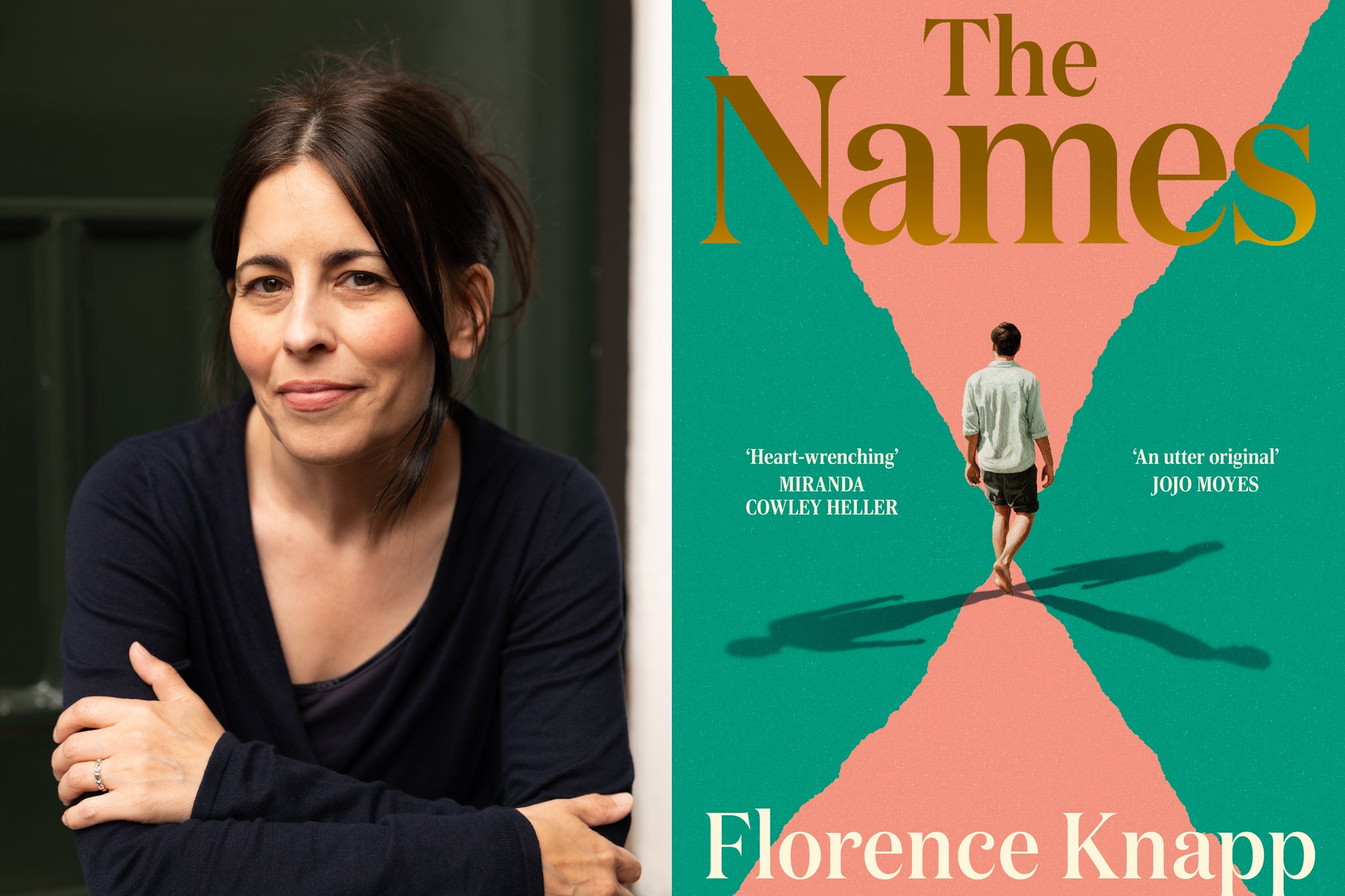

3. The Names by Florence Knapp (Phoenix)

The Names, in simple terms, is the story of three different versions of the same life, with a trio of wildly differing fates fanning out from one simple decision: Cara’s choice of name for her newborn son. Spanning 35 years, Florence Knapp’s scintillating debut novel builds on a clever premise and unfolds subsequent events with a sly unpredictability. The three different life stories are told with imagination and cohesion, and the author also explores wider themes such as teenage misogyny, sexual identity and the power of true friendship. Names is a difficult read at times, but Knapp’s tender touches rescue the reader from some of the pain.

2. No Obvious Distress by Amanda Quaid (JM Originals)

Very unusually, No Obvious Distress is a memoir in verse. Poet and playwright Amanda Quaid is the daughter of actor Randy Quaid and niece of Dennis Quaid – although the only family reference in the book is an oblique one that arrives during a funny, biting account of a visit to a male proctologist. The book deals with her experiences during treatment for a rare and aggressive malignant tumour and utilises a range of prose and poetry styles to construct a memoir that is highly original and simply wonderful.

1. Helm by Sarah Hall (Faber)

Sarah Hall is one of the few writers who is bold and talented enough to pull off a novel in which the main character is the wind itself. In the case of Helm, Britain’s only named wind, it is the blustery northeasterly gust that blows down the western slope of Cross Fell, the highest peak in the Pennine Hills. Hall possesses a shimmering ability to conjure her native landscape in immersive storytelling, and the Cumbrian countryside is a constant delight in a novel that examines the relationship between people and the natural world in a highly imaginative and humorous way. Helm, which was 20 years in the making, will sweep you off your feet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks