Boyd Tonkin: Good books, but a bad business

The week in books

Last week I wondered how HarperCollins might keep its thoroughly deserved good name as a book publisher clear of the contagion spreading from its parent group, Murdoch's News Corp. That remains a fair question, I think. But then, on Friday, came news not of potential harm by some remote association but admitted serious malpractice on the part of a major UK publisher. The firm in question is Macmillan, the fifth largest publisher in Britain, founded by two Scots brothers in 1843 but owned since 1999 by the Holtzbrinck group of Stuttgart, Germany.

After a High Court action by the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), Macmillan has agreed to settle a civil-recovery case with a payment of £11.3m. This, by a margin of more than £4m, is the largest such settlement ever negotiated by the SFO. The penalty comes "in recognition of sums [Macmillan] received which were generated through unlawful conduct related to its Education Division in East and West Africa." Some reports have branded the payment a "fine". It certainly represents a punishment for (in the words of SFO director Richard Alderman) "corporate wrong-doing". The order was made under part 5 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

The World Bank began this investigation after a failed attempt to pay a bribe to win a Bank-funded contract for educational materials in southern Sudan. Following legal guidelines, Macmillan then launched a broader enquiry by independent lawyers that allowed the SFO to assess the "bribery and corruption risk". It took in the firm's activities in Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia, and examined all public tenders there between 2002 and 2009.

Throughout, the publisher co-operated fully and proactively with the Bank and the SFO. It revised its anti-bribery procedures and voluntarily withdrew from future tenders in the region. The SFO took this by-the-book conduct into account in making the settlement, and adds - slightly poignantly – that "the actual products supplied were of a good quality". Macmillan CEO Annette Thomas, while "deeply regretting" the case, states that the company "will not tolerate any form of potentially unlawful behaviour, as our approach to the SFO has demonstrated".

Now, anyone who believes that only one major British company has ever slid into the swamp of inducements and "commissions" in Africa, Asia, the Middle East - or some parts of Europe - has been dwelling not in any of those areas but somewhere much closer to Cloud Cuckoo Land. And let's not forget that bribery also routinely oiled wheels in, for instance, Greece. Wherever officials are poorly paid, their careers fragile and the custom ingrained, overt or covert bribery may thrive. Infinitely worse things have happened in Rwanda, or South Sudan. That doesn't absolve Macmillan, but it does raise the question of how British publishers will fare overseas in the future.

Since colonial times, a few large companies have profited from historical links across the once-pink slabs of the map to sustain a key position in the education market. Some observers with experience in this field have suggested, in the wake of the Macmillan-SFO deal, that tougher anti-bribery compliance measures in the UK may inhibit future business. The new Bribery Act does demand an extra level of vigilance – but note that this case was pursued according to earlier legislation.

It sounds like a barrel-scraping argument: other people do it, so why shouldn't we? In practice, if a provider of first-rate textbooks quits a corruption-prone market and leaves the field open for inferior rivals, the black-and-white of the ethics seminar may blur. And publishers have been showing signs of extra sensitivity of late. Last month, Pearson – parent of Penguin – sold its majority stake in Longman Nigeria. Among the reasons, it cited local "business practices".

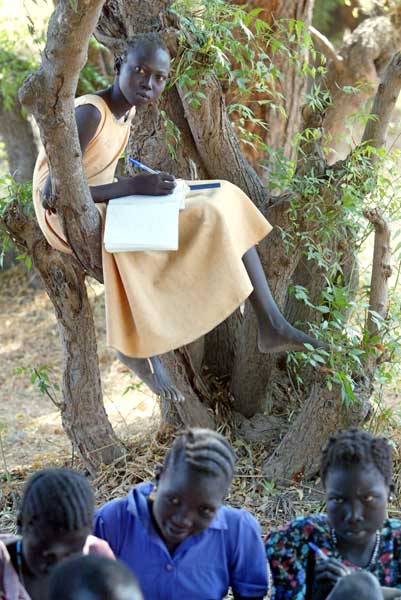

If you believe that the revenues enjoyed by older British publishers from Africa, or elsewhere, amount to post-imperial booty, you might welcome a withdrawal. The view from the African classroom may be more nuanced. However they came to work there, these firms have the power to do enormous good. Of course they should never offer anything like a bribe, anywhere on earth. But the risk-free option of departure from all tricky terrain may teach us a hard lesson in the law of unintended consequences.

Further notes on a scandal

Publishers have already signed up two books from major players in the phone-hacking affair. Tom Watson MP (pictured), the modest hero of the House of Commons investigation, will be co-writing one in tandem with my Independent colleague Martin Hickman; Penguin Press has scheduled their work for later this year. In 2012, Nick Davies of The Guardian – whose original revelations first appeared in 2009 – will publish his own study, Hack Attack, with Chatto & Windus. With such a huge story, several books deserve to thrive. To prove the bona fides of Murdoch's better brands, I would love to see a frank account by a Times or Sunday Times writer – to be published by HarperCollins.

Drawing the fine lines of libel

On 19 December 2008, The Independent selected 20 of the best books of the year. Among them was Seven Days in the Art World by Sarah Thornton, described as "a hard-thinking but high-spirited memorial to that strange... period when contemporary art offered a glittery rendezvous for talent, ambition, hype". Some of those words (which I wrote) appear uncredited on Thornton's own website. Thornton – a critic who writes for The Economist – has just won a case for libel and malicious falsehood against a very different sort of review: Lynn Barber's, in the Telegraph. The case related to statements about the author's professional integrity, not an adverse judgement on the book. It still represents an alarming incursion of libel legislation into reviews pages. Seven Days... was published here by Granta Books. Its proprietor, Sigrid Rausing, champions free speech. Do she and her firm believe that freedom ends where "malice" begins, and that a British libel judge is best equipped to draw that line? This debate has only just begun.

b.tonkin@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks