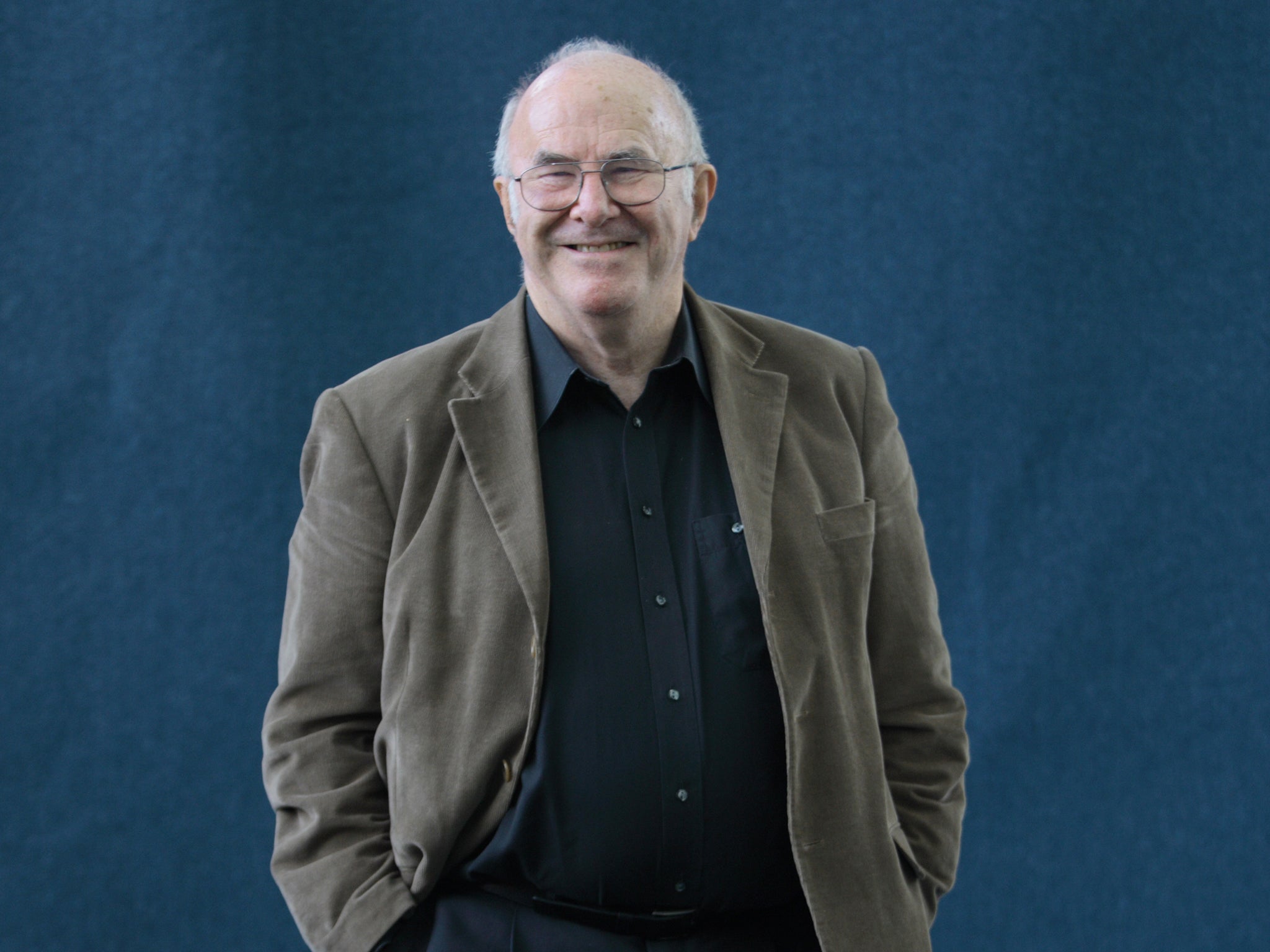

Clive James interview: 'Think of all the millions of people who got killed young – pity them! I've been a lucky man. My subject is luck, not death'

The ailing critic, satirist and long-time poet talks about a last rite

For a moment I think I’ve got the wrong day. I’m standing outside what I hope is Clive James’s neat Cambridge house but there’s no response from bell or knock – that is, until a bandaged head emerges from an upper window and calls cheerily down. He was just having 40 winks, it turns out, understandable for someone who, as he explains, has just had a major operation and gets his “whole immune system replaced every few weeks at Addenbrookes”.

He leads me into the spacious, book-lined kitchen at the back of the house, filled with the remnants of his library. He has recently given lots of his books away, which seems a sadly significant step for such a devoted reader. I’m here to talk about Sentenced to Life, his new collection of poems.

During the Eighties and Nineties, Clive James was one of the most famous people in Britain, a legendary TV critic who became a presenter, and who was also a noted satirist and memoirist. But his first love, all along, was poetry.

“To me the poems are the key thing. I knew a long time ago they would be the last thing I did, and they were almost the first thing I did,” he says, sitting at the long wooden table with a cup of tea.

“At Sydney university in the late 1950s I met my first poets and knew straight away that was what I wanted to do. But it sort of gets lost in the noise, especially if you do other things, and if those other things have anything to do with showbusiness.” He was last regularly on TV 15 years ago, but still gets people coming up and saying “I love your shows”.

Sentenced to Life is a valedictory volume, concerned with the end of life, and with the slow robbery of terminal illness. “Poetry is a good art form in which to sum up,” he agrees. “If you live to an advanced age as I have, you’ve got a lot of experience to look back on and the work improves all by itself. You’re working in a limited space. I like packing a lot in. It’s a value-for-money feeling!”

The poems began to arrive (his favoured expression) after he first fell ill in January 2010. He showed them to his half-dozen trusted first readers. “I was feeling very ill so I needed moral support.” His fingers are working their way to the bandage. “Sorry, I’m scratching – I must stop! I’ve had all kinds of wounds left over from operations and when they heal, they itch! It’s a good sign,” he says, flattening the gauze over his scalp.

After writing poems for 50 years, his technique is deft and assured, but “it’s physically harder [to write now] because it takes a lot of energy”. “More / and more I sit down to write less and less,” as a poem puts it. “I’m not saying you have to be a decathlete to write poetry but you have to be able to concentrate without getting exhausted. I find when the poem comes it demands, still, that I drop everything else. It always did. But that’s a bit easier because there’s comparatively little else to drop.”

He might have “retreated back within my fortress walls here in Cambridge”, but talking to James isn’t at all a melancholy experience. He looks worn at first but the mellifluous Aussie tones are only slightly muffled and with the first delighted beam of amusement he’s instantly the wit and raconteur of old. Every so often, when he has expressed something especially pithily, he leans forward and mutters into the machine, “Put that in”.

When I quip, about a certain baffling modern phenomenon, “What will remain of us is selfies,” he yelps. “Put that in! Larkin would have loved to hear you say that. He had a terrific sense of humour.” Given the subject matter, there isn’t a lot of humour in this book... “There are precisely three laughs in it,” he concurs gravely. He didn’t even see it as a collection; it took Picador’s Don Paterson to point out: “You’ve got a book here.” A constant refrain in our conversation is luck. Paterson as editor: wonderful luck. Coming to England when he did: “a terrific stroke of luck”. And he was “lucky in my timing” to review TV when everybody watched the same thing at the same time and it formed part of the national conversation.

His poems are mostly formal, scanning and rhyming. While he admires the freedom of many new poets, he wonders whether the balance has now gone too far the other way. “It would be a terrible pity if none of the poets could write formal verse any more. But that’s the way it might go. It’s very hard, technically, but I don’t see why poets shouldn’t learn to put a sonnet together before they set themselves free.”

Technical mastery is the key to avoiding sentimentality or self-pity when writing on grim personal topics. “Sentimentality is really an excess of feeling about nothing and the way I avoid it now is quite elementary. I’ve got plenty of things to have feelings about. My poems are true stories in that sense. But tone of voice is everything. That’s the great thing about poetry – everything is everything! Rhythm, imagery… but especially tone of voice.”

I got a lump in my throat, I tell him, at the final line of “Elementary Sonnet” which anticipates a time “when soon my poor bed will be smooth and straight”. “Well, ‘poor bed’ includes the idea ‘poor me’, of course!” he grins. “But there’s no point saying ‘I’m going to drop dead, pity me’. For one thing, that’s not a subject. Think of all the millions of people who got killed young – pity them! I’ve been a lucky man. My subject is luck, not death.”

He thinks for a moment, then leans into the machine. “Not bad! Put that down.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments