Cunning as a fox: The animal kingdom’s most hunted hero has its roots in myth and legend

'Through the sticky pitch of my slimmer, I could hear them barking and sense their confusion as they peered inside the cage once more to find it empty'

The fox is surrounded. A baying mob of vengeful beasts has sworn to see justice done. The red-furred fiend has conned, cheated and tricked his way through the Court of Noble, the realm of the lion king. Now he will pay. The animals grasp him cruelly by his ears, and lash his paws with rope. Bound and bloodied, the fox is led to the scaffold.

The fate of the wicked red fox is chronicled in The History of Reynard the Fox, an epic verse first recorded in Latin in the 12th century. The story characterises many of what we’ve come to think of as fox-like traits of deception, selfishness and guile.

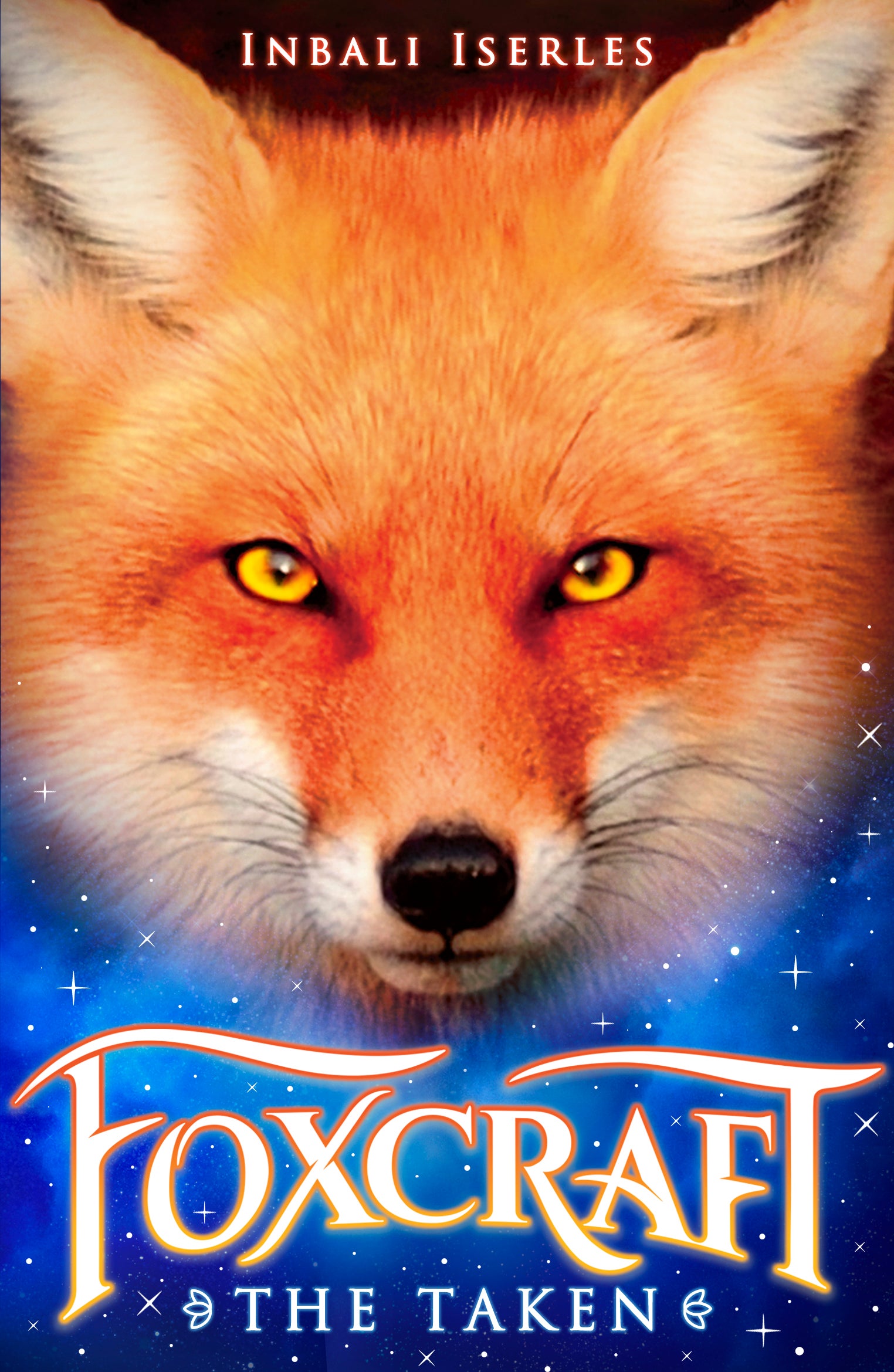

The roguish Reynard is leagues apart from the sensitive animals that share our cities. Enigmatic, fleet of foot, where was the other fox to be found, the dextrous, bright-eyed hero? It was my determination to tell the fox’s story – to write an alternative narrative for Reynard’s successors – that inspired my children’s fantasy series, Foxcraft. The books follow fox cub Isla’s quest to find her family. Alone in the city, Isla must learn to survive in an unforgiving human world. In doing so, she must master the dangerous arts of her kind – the secrets of foxcraft.

While literature is rich in animal archetypes, from noble Aslan to an endless pack of faithful dogs (Tintin’s Snowy, Dorothy’s Toto, Old Yeller and Lassie, to name but a few), the fox’s addition to the canon is dubious. More commonly villain than hero, nemesis to Br’er Rabbit and Jemima Puddle-Duck, even Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr Fox (Puffin, £5.99) sees him succeed by trickery.

These representations all owe a debt to Reynard. The satirical tale of the anthropomorphised court gained favour across Medieval Europe. Adaptations saw versions in French, German and Flemish. Reynard crossed the Channel in 1250, inspiring the wicked fox in Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale” in 1390. His infamy was augmented by William Caxton. A familiar figure in church carvings across Europe, Reynard became a byword for bestial mischief.

What was seen is unseen; what was sensed becomes senseless.

The fox’s portrayal in children’s books has roots in myth and folklore. Aesop famously caricatured them as tricksters. In one cautionary fable, a fox flatters a crow so she drops her supper. In another, a fox proves that one bad turn deserves another by offering a stork dinner in a bowl too shallow for his beak. In perhaps the most memorable depiction, a fox disguises his injured pride (and empty stomach) at failing to reach some tasty grapes by concluding that they must be sour. Be it cunning, hubris or insincerity, foxes do not emerge well from these tales.

The kitsune, the fox of Japanese legend, enjoys a more important yet still morally ambivalent role. In ancient Japan, foxes were deemed to be mystical beings. The kitsune’s most beguiling characteristic is the ability to shapeshift, a skill echoed through fables across China and Korea. This supernatural creature walked among men, disguised as a beautiful woman or itinerant salesman. In Foxcraft, shapeshifting is one of the higher arts. Its exercise is closely guarded by the secretive Elder Foxes.

What is common to the fox of Eastern and Western legend is the animal’s uncertain nature. Fox as trickster, con-artist and wanderer; fox as impermanent, transmutable beast. An unknowable thing without family, loyalty or land. Treading an uneasy space between the familiar and the strange – between her cousins, the domestic dog and the savage, distant wolf – the fox is an enigma.

Humans have persecuted foxes since the two first came into contact, killing them in the name of pest-control or hunting them for fur or sport. In Foxcraft, outwitting human cruelty is the inspiration for fox magic. “It was always hardest for Fox, with so many enemies,” explains Siffrin, messenger to the Elders. “It is foxcraft that saved us.”

Centuries of villainous literary foxes have encouraged a lingering prejudice, making it easier to dismiss them as vermin. Foxes are canids, members of the dog family, but unlike wolves and dogs they never hunt in packs. This has resulted in the misconception that foxes are solitary. In fact, they pair bond, often for life. They commonly live in family units, where cub-rearing duties are shared.

Foxes may claim large territorial ranges, depending on population and availability of food. This has lead some to conclude, erroneously, that they are lonesome wanderers, like Aesop’s trickster or the kitsune of Japanese myth. It is truer to observe that fox behaviour has been shaped by human activity. This is how Isla describes the city in The Taken: “I stole along the bank of the deathway, making my way to the higher climbs. The Great Snarl was a grimy maze of fences and dead ends, of meshing and wire as sharp as talons. The furless liked their walls. Walls to keep them in. Walls to keep others out. The Great Snarl was full of them.”

Perhaps the most misunderstood fox behaviour is so-called “surplus killing”. “Nothing about foxes engenders more hostility than their habit of slaughtering fowl in chicken runs and leaving uneaten corpses,” write Stephen Harris and Phil Baker in Urban Foxes (Whittet Books, £10.99). Contrary to popular belief, this has nothing to do with pleasure or bloodlust. In the wild, the fox will cache uneaten prey, feeding on it for days.

The fox is notoriously hard to tame. With her screeching cries, her distrust of strangers and her questionable table manners, she has proven far less pliable than the dog. “Humans instinctively disapprove of canines too wilful and independent to enslave,” explains Trevor Williams of the environmental charity The Fox Project. “Call it ‘control freakery’.” This sentiment is echoed by Martin Wallen in Fox (Reaktion, £12.95): “As un-domesticable animals, as dubious pets, foxes will always be outside human culture – they remain outlaws, embodiments of what humans, with our need to form regulated groups, cannot abide or understand.”

So, back to Reynard, the perpetual crook. While some versions of his misadventures conclude with his execution, in many accounts he dupes the king and escapes. This feels true to nature, for if the red fox is anything, it’s a survivor. Scattered from Europe to the Americas, Africa and Australasia, and as far north as the Arctic Circle, its gift is its adaptability. Despite centuries of torment, the fox has thrived.

Survival is a message that Foxcraft’s Isla is quick to learn. Alone in the city, refusing to give in to despair, she recalls the words of her grandmother: “We choose to survive, as that is our legacy. We choose to live, and we never give up.”

'Foxcraft: The Taken' by Inbali Iserles is out now in paperback (published by Scholastic).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks