The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Elena Ferrante busted: Why women writers like to use a pen name

The writer behind the bestselling Neapolitan crime novels has avoided having her work put into the boxes reserved for women writers – romance and chick lit

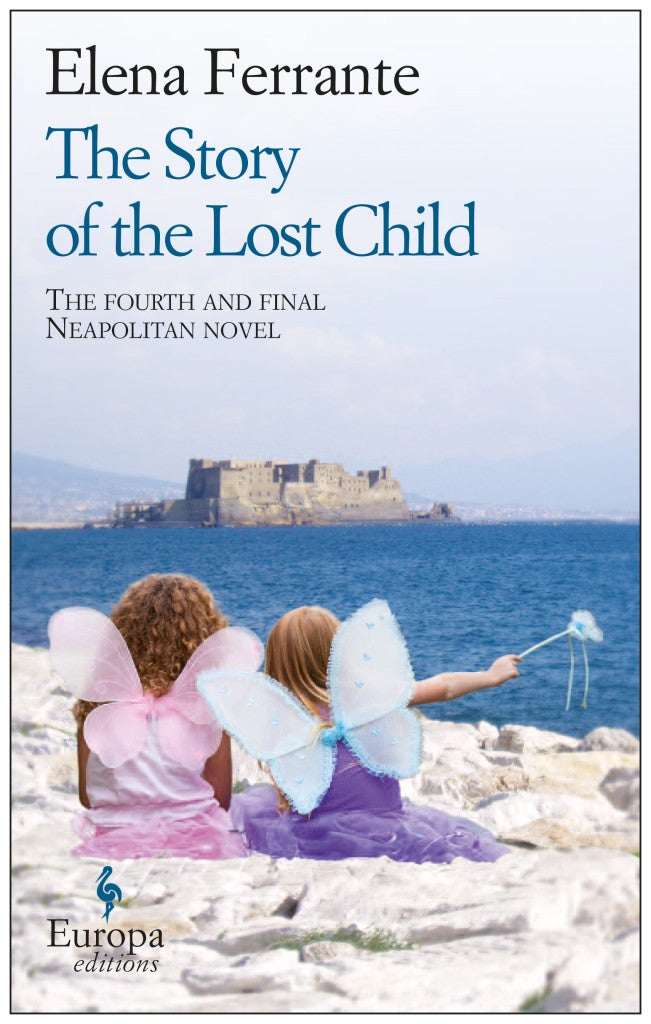

In the New York Review of Books, investigative journalist Claudio Gatti claimed to have uncovered author Elena Ferrante’s true identity. Ferrante, the writer behind bestselling Neapolitan crime novels, has until now been famously anonymous, giving interviews via email, her true identity known only to her publisher.

In many respects, Ferrante’s story mirrors that of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë. The Brontë sisters published their novels Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall under the masculine pseudonyms Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Like Ferrante, they published under pen names to ensure their privacy and to eschew celebrity. In an interview earlier this year, Ferrante stated that she chose to write under a pseudonym so she could “concentrate exclusively and with complete freedom on writing and its strategies”.

The Brontës wrote as men because their novels examined subject matter which was “unfeminine” for their early Victorian readers: sexual passion, slang, alcoholism, domestic abuse and violence. Nevertheless, commentators were quick to accuse the “Brothers Bell” of being women writers, or equally using their writings to affirm that they must be male. Mr Rochester’s slang and sexual exploits were said to prove Jane Eyre’s male authorship, while the detailed evocation of Jane’s psychology and emotions gave away the woman’s hand in the novel.

In the beginning, even the sisters’ publishers did not know the true identity of their suddenly notorious authors. When an American publisher stated that Anne’s novel, Agnes Grey, and Emily’s Wuthering Heights had both been written by the author of Jane Eyre, Charlotte and Anne made a whirlwind journey to London to prove their separate identities. Charlotte famously declared: “We are three sisters.” While Charlotte partially embraced her fame, Emily was upset by her tactics, desiring only to be known as “Ellis Bell”, a male author. As the work of women writers, the novels were deemed “coarse” and “brutal”, the writers themselves “nearly unsexed”.

The novelist Elizabeth Gaskell took part in the parlour game of guessing who the Bells really were. When she discovered the truth, she wrote a triumphant letter to a friend: “Currer Bell (aha! what will you give me for a secret?) She’s a she.” In writing The Life of Charlotte Brontë, following Charlotte’s early death in 1855, Gaskell strategically positioned Charlotte as a pious and self-sacrificing daughter, as well as a talented novelist.

Gaskell’s biography also began a trend that haunts the Brontës to this day. She located the “originals” of the characters and locales in the Brontës’ novels in the people and geography of their native Yorkshire. The Brontës’ novels have been read through their lives ever since. These readings deny the Brontës’ genius, imagination, and literary skill.

Many commentators have denounced Gatti’s investigations, citing Ferrante’s desire for anonymity and privacy. In an age of unparalleled access to authors – through social media and at literary festivals – perhaps it seemed inevitable that Ferrante’s identity would eventually be found out, unthinkable that an author could hide away in obscurity forever.

The Brontë sisters had more control over who knew their secret than Ferrante has done. The critic George Henry Lewes, later to become the partner of novelist George Eliot, praised Jane Eyre in print and corresponded with “Currer Bell”. But Lewes earned Charlotte’s scorn when he criticised her second novel, Shirley, as the product of a woman’s pen, after learning she was a clergyman’s daughter. Charlotte responded with a blistering one-line note: “I can be on guard against my enemies, but God deliver me from my friends!”

Ferrante’s story raises important questions about how we read and value women’s writing and authorship. Ferrante has stated that in part she wants to protect the Neapolitan community she writes about in her novels, just as Charlotte wanted to write about Yorkshire clergymen she knew without fear of discovery. The latter failed. Haworth locals gleefully identified some of the characters drawn from life in Shirley. If known, with a past to be examined, Ferrante’s novels could be subjected to the flattening biographical readings the Brontës’ works have long been subjected to.

Up until now, as an unknown literary quantity, Ferrante has also avoided having her work put into the boxes unfairly reserved for women writers – romance and chick lit. Her in-depth examinations of women’s lives and friendships have been taken seriously. The cultural critic Lili Loofbourow has argued that Ferrante’s “pseudonymity was a gift to her readers. She inoculated us against the urge to reduce her work to her femaleness, family, biography.”

The Brontës’ novels were disturbing and innovative on first publication, but now are sometimes seen merely as semi-autobiographical romances, partly as a result of their Hollywood film adaptations. However, since Sandra M Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic was published in 1979, the sisters’ novels have been revisited as feminist critiques and as works of literary genius – though it took more than 100 years after initial publication of the Brontës’ fiction.

How Elena Ferrante’s works will be received now that their author is, perhaps, known, is yet to be seen. The Brontës’ story could serve as a warning never to lose sight of the work itself.

This article was originally published on The Conversation (theconversation.com). Erin Nyborg is a researcher and tutor at University of Oxford

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks