Sex and rage and bags of talent: It's time to rediscover Eve Babitz, the muse that roared

She's long been pigeonholed as a 1960s groupie, beauty, It girl. But her soon-to-be reissued novel 'Sex and Rage' reveals what a painfully contemporary, and very funny, writer she is

If you’re a woman who wants to make a contribution to art, music or literature, being a muse has long been your best bet. It helps to be beautiful, but it’s more important to be in the right place at the right time and have well-connected friends.

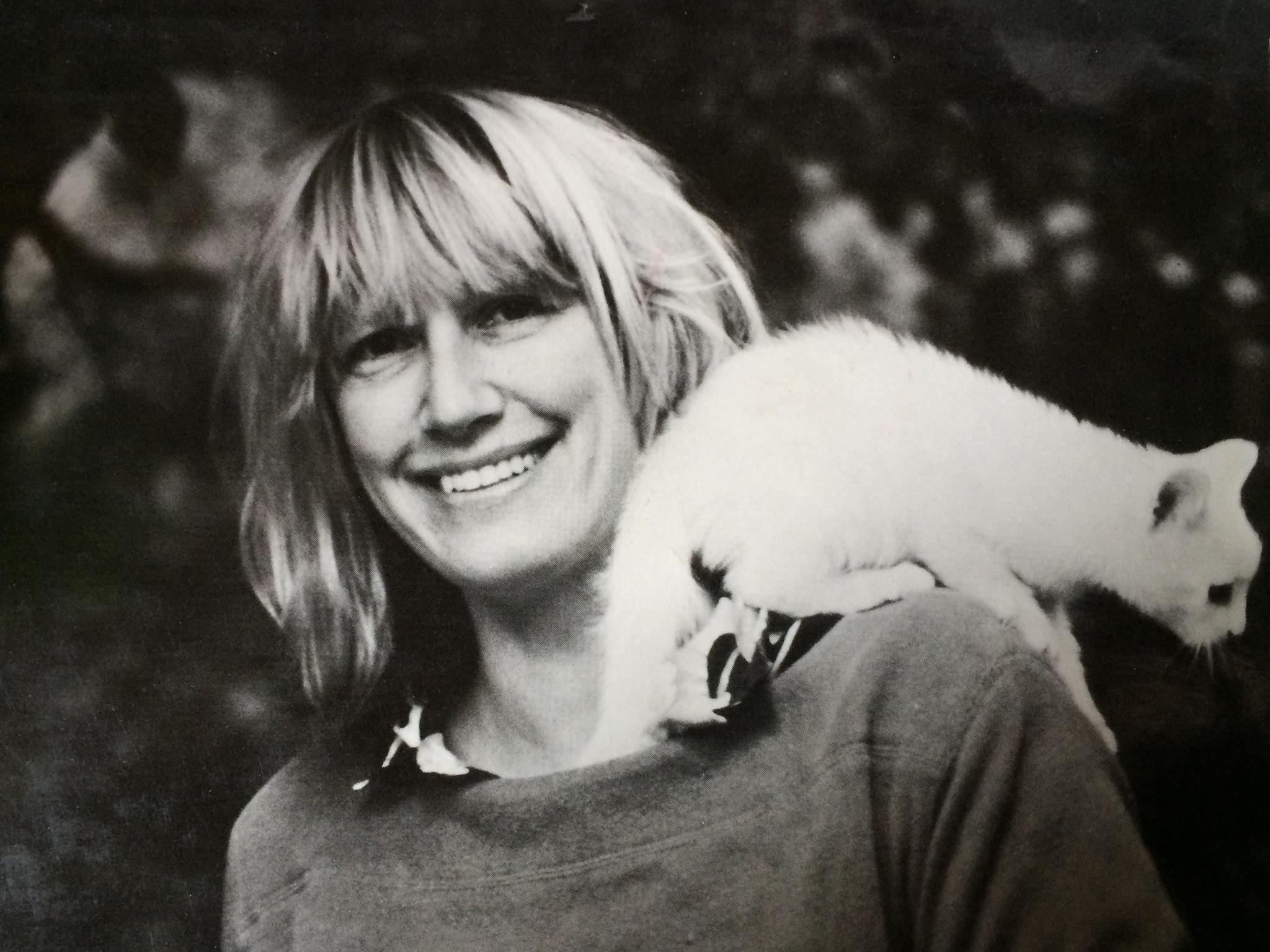

Eve Babitz is overqualified. In the US, she’s the thinking nostalgist’s Edie Sedgwick, remembered for her affairs with Jim Morrison of The Doors and the comedian Steve Martin. In the UK, some of us know her by sight, from a Julian Wasser photo in which she plays chess, nude, with Marcel Duchamp.

But for too long, she’s been seen purely as a muse, her name linked to that body, that photo. In fact, the 75-year-old’s considerable talent as a writer is much more fascinating than her considerable beauty.

Babitz’s reasons for posing the photo that came to define her are relatable – she wanted to get to her boyfriend, Walter Hopps, and punish him for not inviting her to a party he was hosting to celebrate a Duchamp retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum. “I thought I I deserved respect,” Babitz told Paul Karlstrom, from The Archives Of American Art.

And in 1963, when the photograph was taken, young women could earn respect – or at least a useful kind of public notoriety – by taking their clothes off. Being an artist, photographer and writer in your own right was a much less effective route to recognition and success. And so Babitz was pigeonholed by her own beauty.

Yet Babitz wrote several brilliant novels, essays and fictionalised memoirs about her life. I’ve been a fan of her writing ever since I discovered her essay collection, Eve’s Hollywood, which was published in 2016. I have recommended her books to many friends with the words “If Nora Ephron were to write songs for Lana Del Rey, this would be the result.”

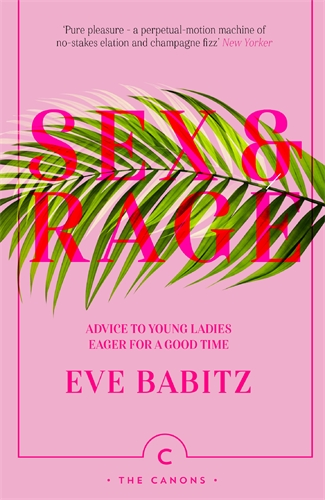

Ephron has long been considered to be the queen of the personal essay, and she’s enjoying a renaissance among Millennial readers with the bestselling reissue of her fictionalised memoir Heartburn. Babitz is owed the same respect, and the same consideration. Now, as her novel Sex and Rage is reissued, she may be about to get it.

Both Babitz and Ephron are women became their own muses. As women who had been seen, watched and judged by powerful men, both knew that the best way to reclaim power is to tell your own story and take control.

Sex and Rage, first published in 1979, is Babitz’s story in every sense. She is the narrator, and the heroine.

The story follows Jacaranda who – like Babitz – is the granddaughter of runaway Catholics and Russian emigrees. She lives in Santa Monica, “at the edge of the ocean”. She surfs. She goes to parties. She falls in love. She drinks, excessively. Then she starts to write, successfully. It makes her friends furious. She sells a book and goes to New York alone, newly sober, and terrified, searching for success as a new means of survival.

Jacaranda’s life parallels with Babitz’s biography, but when your truth is that compelling, why would you bother to make up a new story? Most importantly, Babitz’s talent is in the telling. She surfs between prose and poetry, describing tenderness and cruelty with equally weighted vividness, and lacerates with her wit.

Even though the book is almost 40 years old, the title has is more resonant than ever. Whether we’re watching what’s going on in the White House, or watching Love Island, we’re all consumed by ideas of sex and rage. Jacaranda’s greatest dilemmas feel painfully contemporary.

She’s emotionally abused and gaslit by the man, Max, who purports to be her greatest friend. She’s sought out for her beauty, but instantly discarded when that beauty begins to flicker and fade. She is discouraged from expressing herself creatively (“The women, one by one, took her into the bedrooms of parties and said ‘Don’t write, darling. It’s not nice.’”)

Babitz makes Jacaranda’s dilemma darkly comic: “She was twenty-eight. It was time for her to O.D., not get published.” But through Jacaranda, I think Babitz expresses a very real sadness, and burning frustration.

In every era, women are encouraged to be decorative, discouraged from becoming three-dimensional – and then criticised for their lack of interior life. In part, this book is Babitz’s revenge for this rage-making state of affairs.

(She is also brilliantly waspish about the mediocrity of men: “She’d hated his chin from the first moment she’d laid eyes on him when they were in high school, when he was going around being morose and ‘interesting’ because he was an artist, and so sensitive. All his art – he made iron sculpture – jutted out just like his chin.”)

Jacaranda’s journey to redemption begins, not with a man, but with another woman’s rescue. When the “legendary groupie” Sunrise Honey is assaulted by her boyfriend, Jacaranda arranges for the pair of them to flee to La Jolla.

By observing her new friend, she starts to understand the limitations of how she is seen herself: “Once Sunrise started talking, she spoke so normally one forgot she was just an ornament.” Babitz succinctly explores the link between feminine beauty and internalised misogyny, and gives us a flash of insight into the ways that her own beauty might have isolated her from the kindness and support of her peers: “It was almost impossible to feel human compassion, plain humanity, towards Sunrise, Jacaranda suspected later on, especially if you were a human female.”

The women manage to work through their issues and problems with a thrillingly efficient cocaine binge – but one which ultimately causes Jacaranda to sober up, head to New York. There, she must face her fears: her terror of running into manipulative Max, her horror of meeting her publisher and suffocating under her own imposter syndrome, and her dread of visiting the East Coast itself (she doesn’t believe she can survive so far away from the Pacific Ocean).

Babitz flies in the face of Aristotle, and his theory that “probable impossibilities are to be preferred to improbable possibilities”. Her novels are preposterous, but true.

Every event that seems too strange or glamorous to be believed is usually drawn from her own life – plus, she is not capable of writing a dull sentence.

She so keenly sees herself – and yet other people have continually got her wrong. She did not live simply as a beautiful muse, the perpetually drunk girl at the party. She’s a comic, a poet, and a rare writer who is capable of finding the universal in the unique. She voices feelings and ideas that directly contradict the idea of her that exists in the public imagination, an idea that has made her so easy to dismiss.

It’s time for a new generation to discover her voice, and to learn that it is the most singular, distinctive thing about her. In 2018, we need to look to the muse that roared.

‘Sex And Rage’ is published by Canongate on 5 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks