The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

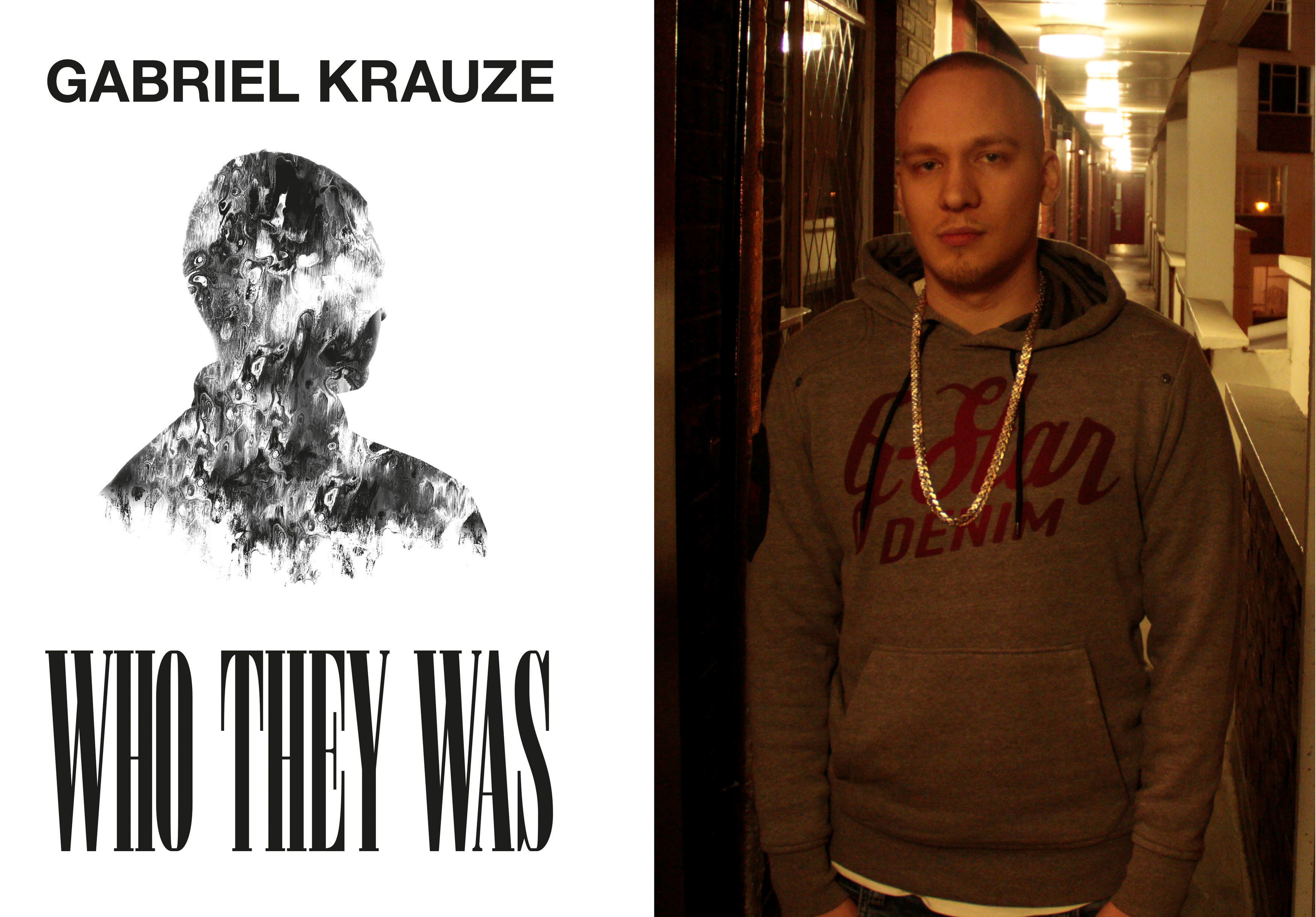

Gabriel Krauze: ‘Literature is mad serious to me’

Krauze is an anomaly in publishing – a novelist whose life and work is steeped in a side of London that many writers don’t even know about, writes Alex Marshall

Leaning over the balcony of a council estate, Gabriel Krauze watches as the police gather in front of a flat below, preparing to smash the door in.

The officers are actors filming a television show, but the scene isn’t so different from ones Krauze, 35, witnessed growing up on this estate.

“When I was living here, the amount of raids I’d see, or just the amount of incidents where the police would come and tape off bits of the estate...” he says. “Like, just there,” Krauze adds, pointing towards one block, “a girl got killed a couple years back.” The TV crew is in fact a good sign, he says, suggesting the area is “calming down a bit”.

Krauze, who has the name of his debut book tattooed on his hand, is an anomaly in publishing – a novelist whose life and work is steeped in a side of London that many writers don’t know about or acknowledge.

His novel Who They Was – published by Fourth Estate and long-listed for the Booker Prize – is a barely fictionalised, first-person account of his late teens and early 20s. At the time, he was living in Blake Court, a tower named after William Blake, which is part of South Kilburn estate in northwest London. (In Zadie Smith’s 2012 novel, NW, a fictional estate is set in the same area, with tower blocks named after philosophers.)

Who They Was is heavy on London slang – people get shanked, not stabbed, and everyone’s “bare loud and aggi”. It starts with a character named Snoopz trying to steal a woman’s diamond ring (“I always thought if you break someone’s finger you’ll actually feel the bones break, hear it even, but I don’t feel anything at all, it’s like folding paper”), then documents Snoopz’s life, including stabbing a drug addict in the head and breaking his favourite knife in the process, stories of honour and revengeand ultimately going to prison.

I was in a youth club, and someone right next to me just got poked up, blood all over the floor, boom, boom, boom

There are breaks from the violence, as Krauze’s character completes an English degree on the other side of London, hangs out with friends and escapes back to his parents’ house, but reviewers have pointed out that there is little optimism.

“That is, I suppose, the only honest way to tell the story,” Jake Kerridge wrote in The Daily Telegraph.

“I had to have a shower after I read it,” Lemn Sissay, a poet and Booker Prize judge, says in a telephone interview. “I never heard this world spoken in this way before,” he adds. “It’s not trying to give excuses, it’s not trying to contextualise the underclass. It’s saying, ‘This is what it is.’”

Douglas Stuart, who won last year’s Booker for Shuggie Bain, his debut novel about working-class life, says in a phone interview: “When you read these worlds in books, it’s normally by a middle-class writer who creates a one-dimensional villain, but Gabriel’s created a world so rich in detail, and motivation and consequence.”

Krauze insists that the book is far more than a lurid tale.

“It’s a moral confrontation with the reader,” he says, contending that it forces readers to realise that some people commit crime because of their psychology, as well as poverty or a lack of opportunity.

The author’s note in some editions of the book is clearer still. “This is the life I chose,” he writes. “Maybe I was looking for a sense of family and identity that I couldn’t find at home. Maybe it’s the way I found my people and they found me.”

Krauze was born in northwest London to a newspaper cartoonist and a painter who had both immigrated from Poland. He grew up round the corner from South Kilburn estate, in a flat where his twin brother practiced violin for hours a day. He became obsessed with books as a child, devouring everything from Tolkien to nonfiction about World War I, and realised that he wanted to become a writer by the time he was 13.

That same year, he also threatened someone with a knife for the first time and saw his first stabbing.

“I was in a youth club, and someone right next to me just got poked up, blood all over the floor, boom, boom, boom,” he says.

At 14, Krauze was arrested for the first time after he was caught stealing videocassettes. He began spending more time on South Kilburn estate with his friends, partly to escape his mother’s glare. By 17, he was involved in so many brushes with violence and the law that he started writing it down – on scraps of paper, in mobile phones — insisting that he would one day turn it into a book. At one court hearing, he joked with his lawyer about the books he should read in prison.

“Crime and Punishment,” Krauze suggested.

“Maybe something more penitential like The Pilgrim’s Progress,” the lawyer replied. Krauze scribbled the conversation down on the back of a probation report. He went to prison twice – once on remand while at university. Being white helped get him shorter sentences, he says, adding that he is aware of the privilege his skin colour gives him compared with his friends.

Krauze spent most of his 20s dealing drugs, he says. It wasn’t until he was 31 and deeply frustrated with life, that he took the notes he’d written and turned them into Who They Was. He wrote the book by hand in four months, he says, then Googled “how to get a literary agent” and started sending it off.

One striking aspect of the book is its lack of redemption, with Snoopz never showing remorse. The first agent Krauze approached asked him to add a moment when Snoopz realises the error of his ways and changes. Krauze refused.

“A redemptive narrative arc would have been a total contrivance,” he says. “If you want to know what this life’s like, you need to have the reality of it, and the reality of it is brutal and grim.”

You can dance around the work and his life, but fundamentally, he’s a writer of beautiful sentences

While writing the book, he found a note he’d written in prison.

“It was this rant against society, me talking about ‘we’re the wolves and they’re the sheep,’ and all this stuff,” he says. “I was shocked, because I couldn’t believe I used to think like that.”

As much as Krauze is now apologetic for his past, he isn’t trying to distance himself from it. Many of the book’s characters are based on his friends, and it shows the intense bonds between them, partly built from what they saw together.

“It’s not like I lived in this world, now I’ve run off from it and written a book about it,” Krauze says.

Despite (or because of) the book’s acclaim, Krauze has faced some awkward moments. Last autumn, a journalist from The Times opened an interview by asking Krauze if he was carrying a gun, then made prominent reference to his diamond dental grill.

Joel Golby, who edited three short stories by Krauze for Vice magazine, says seeing him as a one-note writer is a mistake: “You can dance around the work and his life, but fundamentally, he’s a writer of beautiful sentences.”

Krauze is already moving on to topics beyond his life in South Kilburn. His next novel is going to be about how trauma is passed down through generations, he says, focusing on people like his Polish parents, who were born shortly after World War II, when the Nazis had tried to destroy their country.

“This isn’t a game,” he says. “Literature is mad serious to me.”

He then riffed on a quote from Martin Heidegger, the German philosopher.

“What I’m trying to do with my art is to encapsulate the truth of being — the truth of existence,” Krauze says. He’s done it for a handful of people on one London estate; he can do it for other people, too.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks