What a shed in Cornwall tells us about Britain’s shameful housing crisis

While Catrina Davies’s book ‘Homesick: Why I live in a Shed’ is written from the perspective of a woman struggling to make it as a musician and writer, its relevance is much broader in a country where average house prices have tripled in the last four decades, writes our book columnist Ceri Radford

I started reading Homesick: Why I live in a Shed expecting a quirky, uplifting memoir from the cute cover and punning title. It soon became obvious this was something rather different: a resonant hymn of hatred for a housing market that has made home ownership impossible for most people under the age of 40, opening up bitter wealth and generational divides.

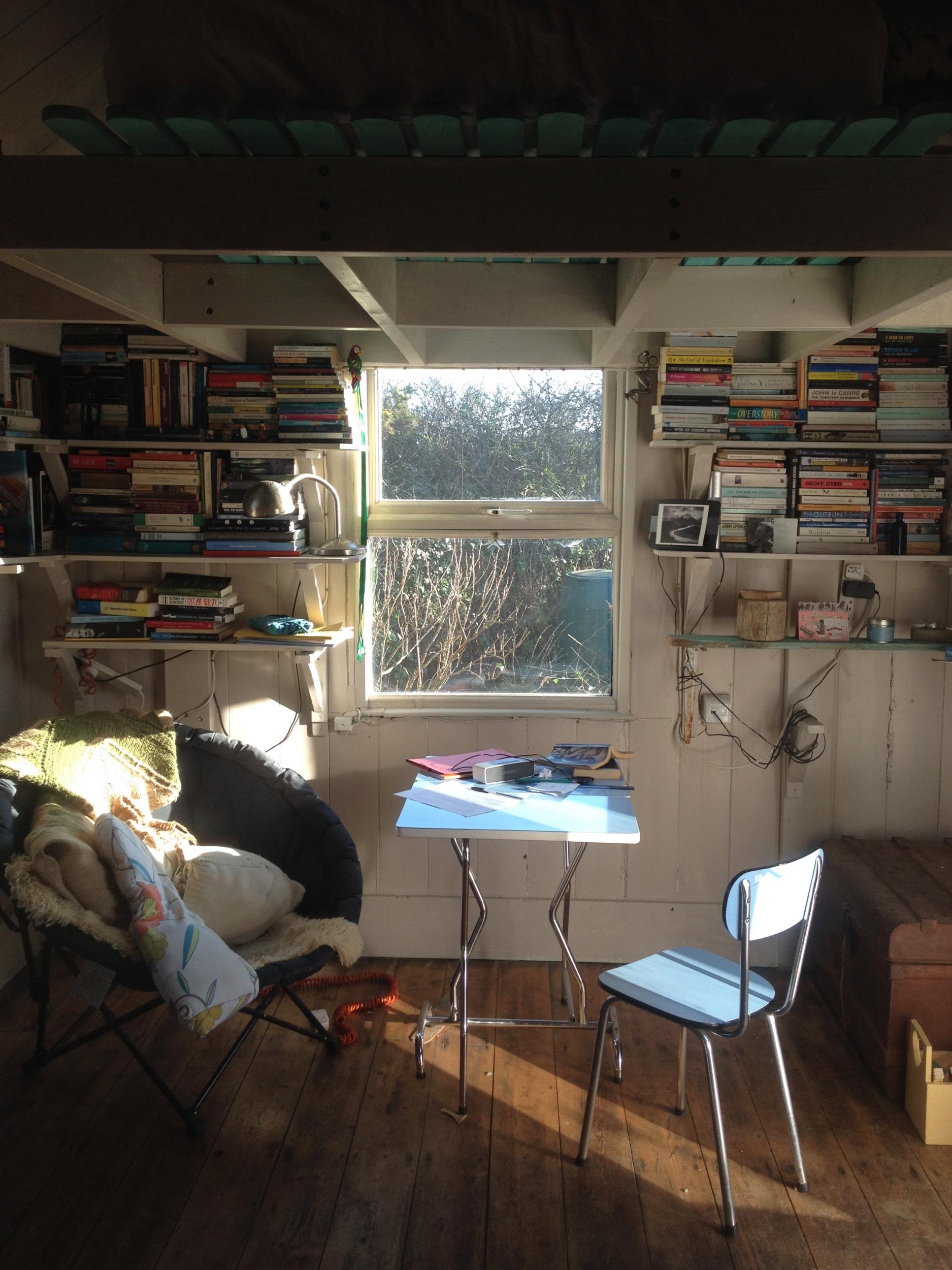

Catrina Davies didn’t end up in a shed simply out of eccentric choice or a strange love of the scent of sawdust, but because it seemed like the least bad choice open to her. In her thirties and on an erratic income teaching the cello, she was fed up with spending £400 a month to rent a dark box room in a house in Bristol that she shared with four other adults and a child. After one pinched milk incident too many, she stuffed her things into bin bags and drove to Cornwall, where a standalone shed that her father once used as an office seemed like a reasonable place to camp out for a while.

The derelict building was full of holes, rats and spiders, but when you consider the basic facts of the relationship between house prices and wages, it’s hardly surprising that the move became permanent.

As Davies writes: “Average house prices had grown about seven times faster than the average income of young people since I turned 18. When I left university, a deposit to buy a starter home in the UK was about nine months’ average salary. Ten years later, it was three years’ average salary, and rising. If food prices had risen as fast as house prices in the years since I came of age, a chicken would cost £51 (or £100 for those living in London).”

It’s brunch-gate all over again, but with more cold, hard context and lyrical descriptions of her seaside roots. (In 2017, an Australian real estate mogul suggested millennials would be better able to afford homes if they stopped splashing money on fancy brunch like avocado toast, despite the fact that it would take a toast mountain the size of Everest to put down a deposit.)

Of course, artistic types have always scrimped and suffered. JK Rowling famously began writing her Harry Potter books in a cafe because it was warmer than her flat; Cormac McCarthy was kicked out of a cheap motel for failing to pay the rent. But what has changed today – and what this book makes so eloquently clear – is that the stakes are higher, the odds longer for anyone trying to eke out a living without the luxury of a family home behind them. If yesterday’s artist starved in a garret, today’s would roll her eyes because all the garrets were booked out on Airbnb months ago. As Davies writes in her blog: “I do not think that only individuals with trust funds should have the chance to be artists. I do not think this would be good for people or for art.”

Given that she lacked a stable family home to fall back on – her father’s business went bankrupt, her mother suffered a mental health breakdown – the shed seemed like the closest thing to a safe haven.

While Homesick is written from the perspective of a woman struggling to make it as a musician and writer, its relevance is much broader in a country where average house prices have tripled in the last four decades. The tourist haven of Cornwall – so beautifully evoked in this book you can smell the salt in the air – is both idyllic and troubled, an extreme version of the divides playing out around the UK. Davies writes of teachers leaving because they can’t afford a home, and local families including her sister moving into tents every summer because renting their homes to tourists is the only way to pay the mortgage. The situation is best summarised as Davies flicks through the local paper, The Cornishman, to find less than a page for jobs and a 40-page supplement for houses. It’s the same crisis that came across so memorably in the recent best-seller The Salt Path, chronicling an extraordinary couple’s walk along the South West coast, with its population of the rural homeless, of seasonal workers making camps in the forest because they were priced out of homes.

Living in a shed isn’t exactly a solution for everyone, but it makes for a rare gem of a book: a combination of underdog page-turner and political tract that raises some of the biggest questions of the day, even if it can’t hope to answer them. There are triumphs (surfing at dawn with seals for company, installing a wood-burner) and trials (fear of being evicted, a theft, a slug-in-thermos incident), all captured in fluid, poetic and provocative writing.

Not only is the relationship between work and home broken for a priced-out younger generation that the economist Guy Standing has labelled “the precariat”, but so is our relationship with the natural world. Davies writes about her childhood in Cornwall, playing with her friends, “Oblivious to the fact that these years of perfect freedom, in a world of sparkling rivers, fertile soil and clean air and a sea full of fish, would turn out to be a kind of curse. The years in this valley were the highlight of my childhood – as they would have been of any childhood – and they would cast a long shadow over my life. I would spend much of my adulthood watching the world I loved disappear, grieving, counting the losses one by one, trying to find my way home.”

The connection with home is personal, the means to afford one political. While housing is particularly extortionate in a tourist hotspot, the national statistic she cites are sobering: between 2000 and 2015, homelessness in the UK rose by 40 per cent, while in 2017, Shelter estimated one in every 200 people in Britain to be homeless.

Other countries take a very different approach to the meaning of home: while owning your own place is embedded in the British psyche, renting is the norm in much of Europe. The first time I moved into a rented flat in Geneva I was astonished that I was expected to provide everything – even curtain poles – and that the flat was a plain white box. I soon came to realise that the curtain poles were symbolic of a very different attitude to renting, where your rental home feels yours in a more meaningful way. Rent increases are controlled by the local government, you can’t be easily kicked out, and there’s an informal rule that you will only be given a tenancy if the rent is around a third of your salary, which helps to keep rent prices in proportion with wages. The system has many faults, but it feels more stable than Britain’s housing rollercoaster. Elsewhere, Berlin is mulling a five-year freeze on rent prices.

It would take another kind of book entirely to unravel the causes of the problem and explore the solutions, but Homesick is a vivid, if partial, glimpse of where we have gone wrong. It’s a rain-lashed wake-up call for a country that has turned on the property porn TV programmes and pulled the curtains on the desolate view outside for too long.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks