‘I felt a sudden stab of pain in my heart’: A medieval guide to love and dating

Valentine’s Day may be here but this is no time for romance, says Ceri Radford. For a bracing dose of perspective, you could do worse than ‘Medieval Legends of Love & Lust’, a new anthology of myths and folktales

Valentine’s Day 2021 feels like someone up there is having a laugh. This is no time for romance. If you’re single, your dating life is drier than the Atacama Desert after someone’s gone over the whole thing with a blowtorch. This year, the prospect of a partner is less about shared interests, more about shared microbes. Couples in different households are kept cruelly apart, and those cohabiting are kept even more cruelly together, deprived of nights out or time alone, forced to spend endless tracts of time staring at the same four walls and noticing the sound the other person makes when they chew.

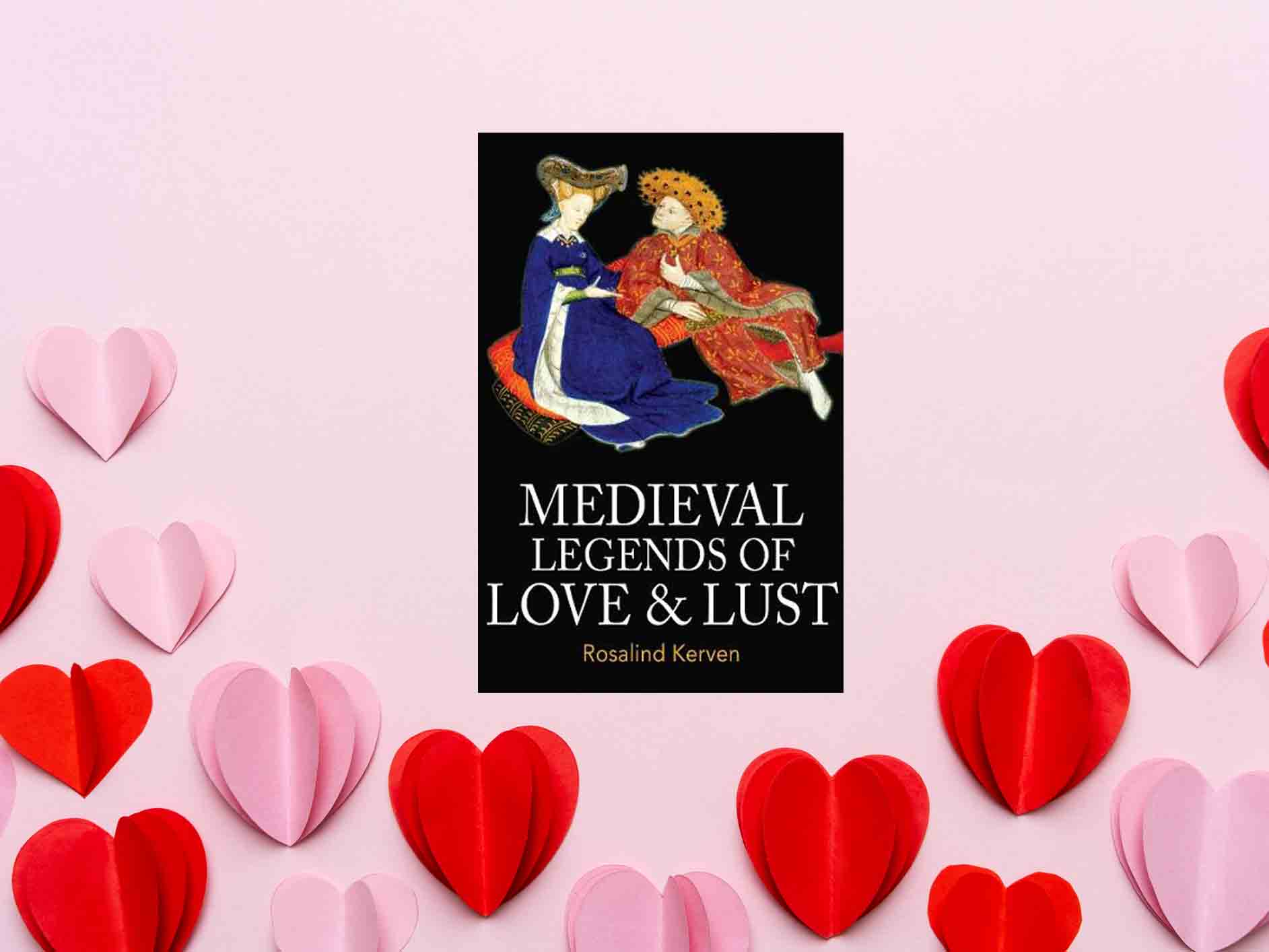

As ever, comfort arrives in the form of a book. For a bracing dose of perspective, you could do worse than retreat to an armchair with Medieval Legends of Love & Lust, a new anthology of stories by Rosalind Kerven, connoisseur of myths and folktales.

Kerven has translated and condensed sprawling, beautiful but inaccessible original texts from the 12th to 15th centuries into concise, elegant tales. Capturing Christian, Muslim and folk influences at play in western Europe during this period, they celebrate romantic love at the same time as offering some salient points of comparison. Sure, it may be months since you last had a date, but at least you’re not Abelard, a 12th-century rogue punished for having an extramarital relationship by having “the parts of my body with which I had committed my crimes” chopped off.

Customs change, wimples go out of fashion, young women are no longer locked up in towers, but human nature remains stubbornly familiar. From across the centuries, here are some lessons today’s lockdown lovers can glean from the medieval tales.

1. Expect and embrace pain

One of the defining features of early medieval literature was courtly love – the noble devotion of a knight towards a lady who was often older, and often married. This form of passionate chivalry put the spring in the stride of Arthur’s knights in works by writers such as Chrétien de Troyes, and sat at stark odds with Christian views on sex and marriage. It was also closely allied with suffering. In the tales gathered in this story, the idea of cupid firing an arrow was less cute Valentine’s card motif, more mortal blow. Stricken lovers sobbed and swooned in a way that made today’s footballers look positively restrained.

As Kerven writes in the voice of the young hero in the allegorical tale “The Romance of the Rose”: “As I was gazing at this rose, I felt a sudden stab of pain in my heart. A great chill rushed through my blood and the next moment, I fainted. When I came round, I felt extraordinarily weak… That was when I finally noticed the god of Love. He had shot an arrow at me!”

Love isn’t meant to be fun. You’re supposed to writhe in agony, especially in the first throes of unrequited passion. In fact, a common and particularly creepy theme in these stories consists of men telling women they will kill themselves unless they “have mercy” – which reads like a sort of medieval primer on coercive control.

While emotional blackmail for sexual favours is best consigned to the history shelf, it’s reassuring to read stories that make you accept that misery is entwined in the human experience of love, or feel grateful that cupid can’t fire his arrow from a distance of two metres in the first place.

2. Play the long game

Another key element of courtly love was the knight’s quest, when a young man would ride forth to prove his worth to his lady by conquering a couple of kingdoms, rescuing some damsels and maybe slaying a dragon or two. These efforts were somewhat more gruelling than making it to the local Sainsbury’s before they run out of chocolate biscuits. In “Lancelot of the Lake”, an anonymous tale from 13th-century France, Arthur’s Queen Guinevere is instantly and unsurprisingly smitten by an upstart who goes by the name of “Handsome Foundling”. She has to wait months, then years, for him to gad about on adventures before he makes a triumphant return, discovers his true identity as Sir Lancelot, and hops into bed with her. Waiting is part of the game for medieval lovers, and the patient are usually rewarded – a reassuring thought for lockdown.

The Lancelot tale also shows the complexity of courtly love: Guinevere is portrayed as genuinely dedicated to both her husband and her lover. When Arthur is imprisoned by a rival, Guinevere is devastated and turns to Lancelot to rescue him, a feat he willingly performs. Concepts of loyalty and duty were more elastic than you might expect.

3. Don’t try to take charge

Close confinement brings out the cutlery drawer tyrant in all of us, but control freakery makes a poor companion for romance. As Chaucer wrote in “The Franklin’s Tale”, one of his Canterbury Tales, “Love will not be constrain’d by mastery / When mast’ry comes, the god of love anon / Beateth his wings, and, farewell, he is gone. / Love is a thing as any spirit free.”

One of the stories included here is “The Promise”, which draws on the Franklin’s account of a married couple named Arveragus and Dorigen. The tale hinges on the sort of happy marriage that would withstand a year in tier 4, showcasing an equal partnership at a time when, in Kerven’s retelling: “The law states that a husband has absolute authority over his wife.” Not so for Arveragus: “He believed that, to ensure a long and happy marriage together, both parties should willingly submit to the other… No one wants their spouse to treat them like a slave. Besides, we all make mistakes sometimes, but there’s no point responding to them with angry words; it’s always better to be tolerant and patient.”

So easy to agree with, so hard to enact when life is an enervating juggle between work, homeschooling and a laundry basket that is evolving into an independent life form.

Whether it’s simple escapism or century-spanning wisdom, this is a book to savour as you’re giving the Valentine’s night out a miss.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks