Jim Crace, author of Booker-shortlisted Quarantine: 'I'm leaving Craceland'

He has written his 11th novel: a Hardy-esque meditation on change. Now he intends to retire, he tells Stephanie Cross

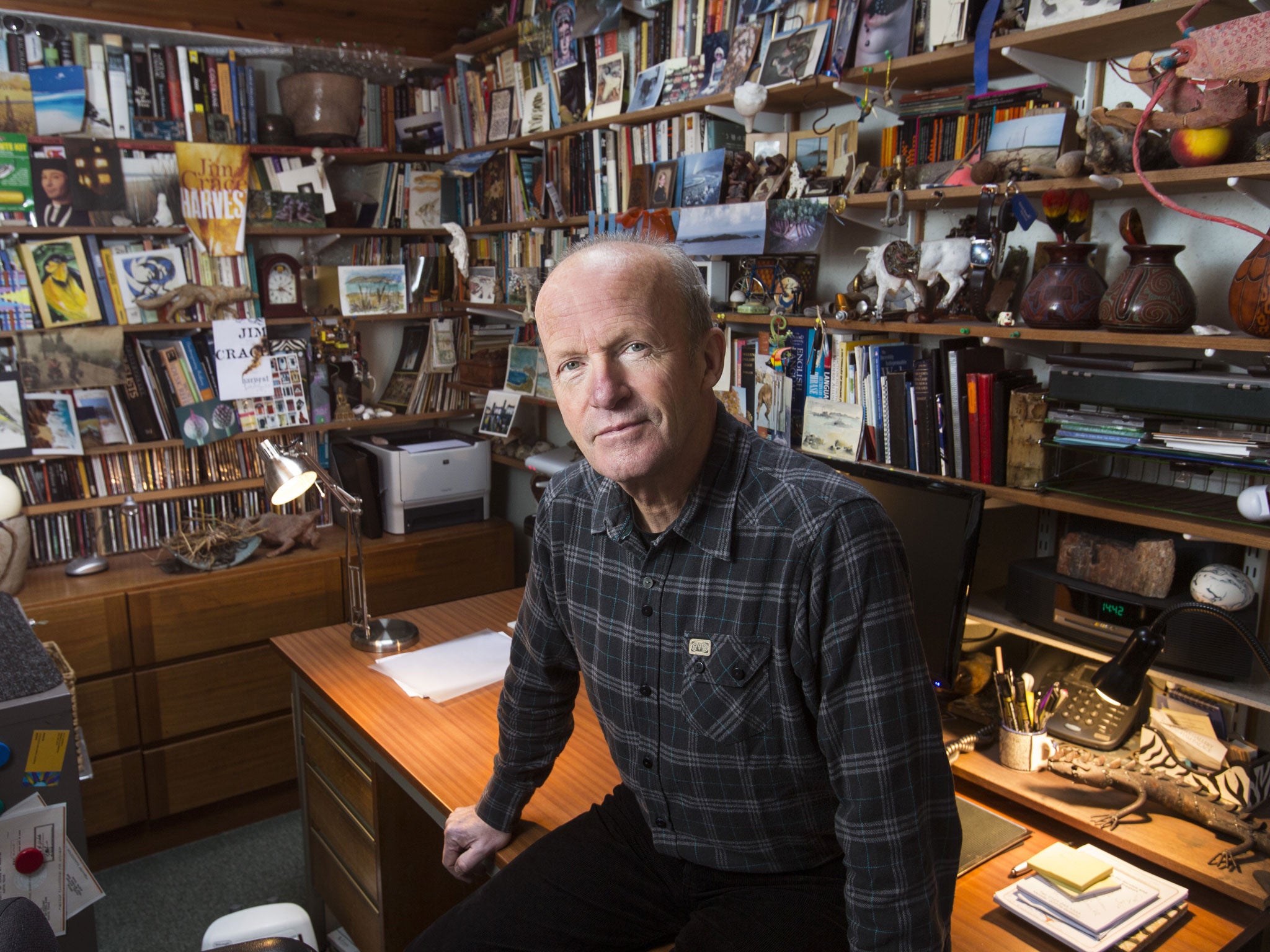

As the protagonist of Harvest, Jim Crace's 11th (and probably last) novel reflects, you can't tell from a man's work how he might live in private. And so it proves. Crace – warm, hospitable, unfailingly modest and self-confessedly private – inhabits an unexceptional semi in the Birmingham suburbs. His paternal acre – the phrase is from Alexander Pope's "Ode on Solitude", and serves as Harvest's epigraph – is short and narrow, albeit carefully tended. Indeed, the only real glimpse of that strangely nebulous yet uncannily familiar place "Craceland" is in the author's study: a book-lined den filled with brass geckos, twigs and fossils.

Yet, set as it is against the backdrop of the enclosures movement, Harvest is saturated with the English countryside; the "bread-and-biscuit smell of rotting wood. The piss-and-honey tang of apple trees", for instance. The madding crowds may be on Crace's doorstep, but his deeply atmospheric tale of an outsider whose life is changed forever by irresistible forces is, I say to the author, Hardy-esque. At which point, Crace's face drains. Clearly, we need to talk about Thomas.

As it turns out, Crace hasn't ever read a Hardy novel, but this isn't the issue. He explains that his "little shiver of horror" was instead at the thought that he might suddenly be seen as a "typically English novelist [when] I've resisted making landscapes which are obviously English." It's true that Harvest is unmistakably set in England, Crace continues, but he was careful to avoid giveaway place names and dates. He isn't sure when it's set himself. "I don't want people to come to it thinking that this is an English historical novel. And I particularly don't want any reviews from English historians, because all they're going to do is say, 'That's wrong, this is wrong.'"

Unlike Hilary Mantel ("That very fine and best of all historical novelists at the moment"), he doesn't go in for research; the convincing descriptions of ploughing and parchment-making in Harvest were "scammed". It's having the freedom to invent that Crace prizes. "I'm a fabulist," he says simply, and it's clear that he finds the whole business of making things up a joy.

Crace's gift is not, perhaps, one that he would have chosen. Born in 1946, he grew up in London, studied English at a Birmingham college, then spent a spell in the Sudan with the VSO before becoming a journalist. Journalism "felt like a political act", he reflects, and he relished the idea that his copy might change minds. But when he made the move to fiction, he found that the direct approach didn't work: "You can't sing baritone when you're a soprano." And it is for this reason, Crace explains, that Harvest harks back to the enclosures, and isn't about the displacement caused by soya farming in present day Brazil.

The community on the cusp of sweeping change is a favourite subject of Crace's: take the The Gift of Stones (1988), set on the brink of the bronze age but inspired by the loss of industry in his adopted home city. And here is why this keen walker, cyclist and bird-watcher isn't to be found in some leafy little village. "The problems of the world are not going to be engaged with and solved in Faversham, they're going to be sorted out in cities like Birmingham," he enthuses. "You're not seeing the past replayed, you're seeing the future played out. And so even though you might not say it's pretty and it's beautiful, it is immensely stimulating".

All of which mean that Harvest is not a simple tale of paradise lost, but something altogether more nuanced. His, Crace says, is "the Jungian idea that everything new worth having is paid for by the loss of something old worth keeping." He pauses. "Now that is beautiful. It's such a balanced sentence for a start."

The appreciation is a connoisseur's. Crace's prose – percussive, rhythmic, resonant – is unmistakable. But not only does it come naturally to Crace; he argues that it's also in keeping with the rhythmic nature of everyday speech. Apparently, academics proved that the prose in his Booker-shortlisted Quarantine (1997) fulfilled a mathematical formula for poetry – as too, he informs me, did most of the verbal exchanges that the researchers studied.

But if Harvest is vintage Crace, it's not the book that he set out to write. For the two years preceding he had been grappling with a "very personal, heartfelt novel" about a reunion with his now dead parents. Archipelago, as it was called, was born in part from Crace's belated fear that "there was no real personal risk of revelation in my books", and that this somehow "lacked generosity" on his part as an author. Once more, though, he was "singing in the wrong key. I am a private person: I couldn't give myself to the novel." The realisation left him depressed. (Or, "as depressed as I can get, which isn't actually too deeply".) Then, on a train passing through the Watford Gap – a place for which Crace makes a typically passionate case – he glimpsed the anciently ridged-and-furrowed fields. Six months after, Harvest was in the bag.

Crace is still haunted by Archipelago, however, and may yet write it as a playful, "Borgesian" essay. As for fiction, he's almost certainly through. "Retiring from writing is not to retire from life," he says: there's his painting, politics and tennis, as well as his first grandchild and regular trips to the US – Crace has a sinecure at the University of Texas, where his archive is held. "But," he continues, "retiring from writing is to avoid the inevitable bitterness which a writing career is bound to deliver as its end product, in almost every case." The idea that Crace could ever become bitter is, in truth, laughable – but, having read Harvest, few will begrudge him bowing out on a high.

Harvest, By Jim Crace (Picador £16.99)

"It is the evening of this unrestful day of rest and the far barn that has survived the fire is full of harvesters, lying back on bales of hay and building up an appetite on rich man's yellow manchet bread from Master Kent's elm platters. We're drinking ale from last year's barley crop. Again we benefit from seasons."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks