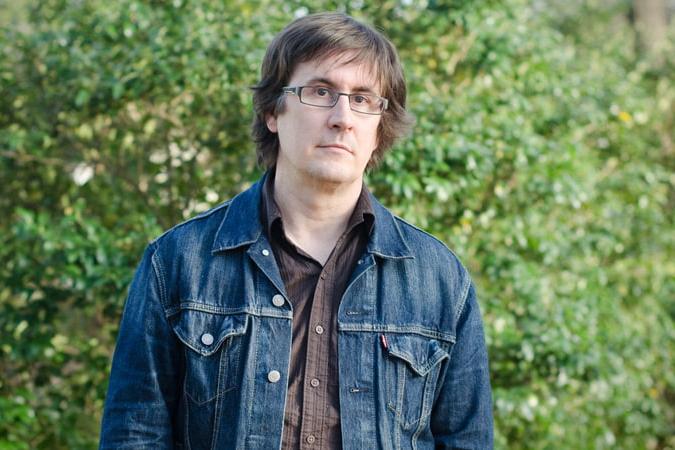

The Mountain Goats' John Darnielle on novel writing: 'I think what the artist makes can be very special, but the artist himself isn’t'

The Mountain Goats’ singer-songwriter, whose novel ‘Universal Harvester’ has been praised by Kazuo Ishiguro, joins a host of other musicians who have turned novelists

“When you are writing a song, your space is vast, but it’s not infinite. Whereas fiction really is infinite.”

So says John Darnielle, who knows a thing or two about writing songs and novels. Described by Rolling Stone magazine no less than “rock’s finest storyteller”, Darnielle’s day job is the singer-songwriter for indie rock darlings The Mountain Goats. In 2014, he turned to stories of a different sort, publishing his debut novel, Wolf in the White Van. Shortlisted by the prestigious American National Book Award and named as a debut of the year in this newspaper, it won Darnielle a new set of admirers including Donna Tartt. Tartt was one of the first people to read Darnielle’s second novel, Universal Harvester. “She is an incredibly insightful, patient and gentle reader. She’s a great teacher.”

By turns unsettling and moving, Universal Harvester has cemented Darnielle’s position as the world’s best singer-prose-writer. It has been longlisted for the rather good ‘Not the Booker Prize’ and earned the admiration of the Times Literary Supplement, who called it ‘A bewitching and eerily still piece of fiction’ and Kazuo Ishiguro who writes ‘it begins like a spooky thriller, then opens out into a moving, beautifully etched picture of America’s lost and profoundly lonely.’

These glowing reviews suggest that Darnielle is overshadowing previous rock writers like the newly-crowned Nobel laureate Bob Dylan who produced Tarantula during his 1960s heyday, less a novel than a rambling stream of consciousness that might have worked better as a sleep aid. More fun, if no more coherent was John Lennon’s In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works, which cut Lennon’s native wit with a dash of Lewis Carroll. Leonard Cohen made a more concerted stab at the form, producing two novels (The Favourite Game and Beautiful Losers) before realising his talents lay in poetry and song. In 2014, Tears for Fears’ Roland Orzabal produced Sex, Drugs & Opera, about a middle-aged pop star attempting to refresh both his personal and professional life on a reality show. Any resemblances to real life were quite deliberate.

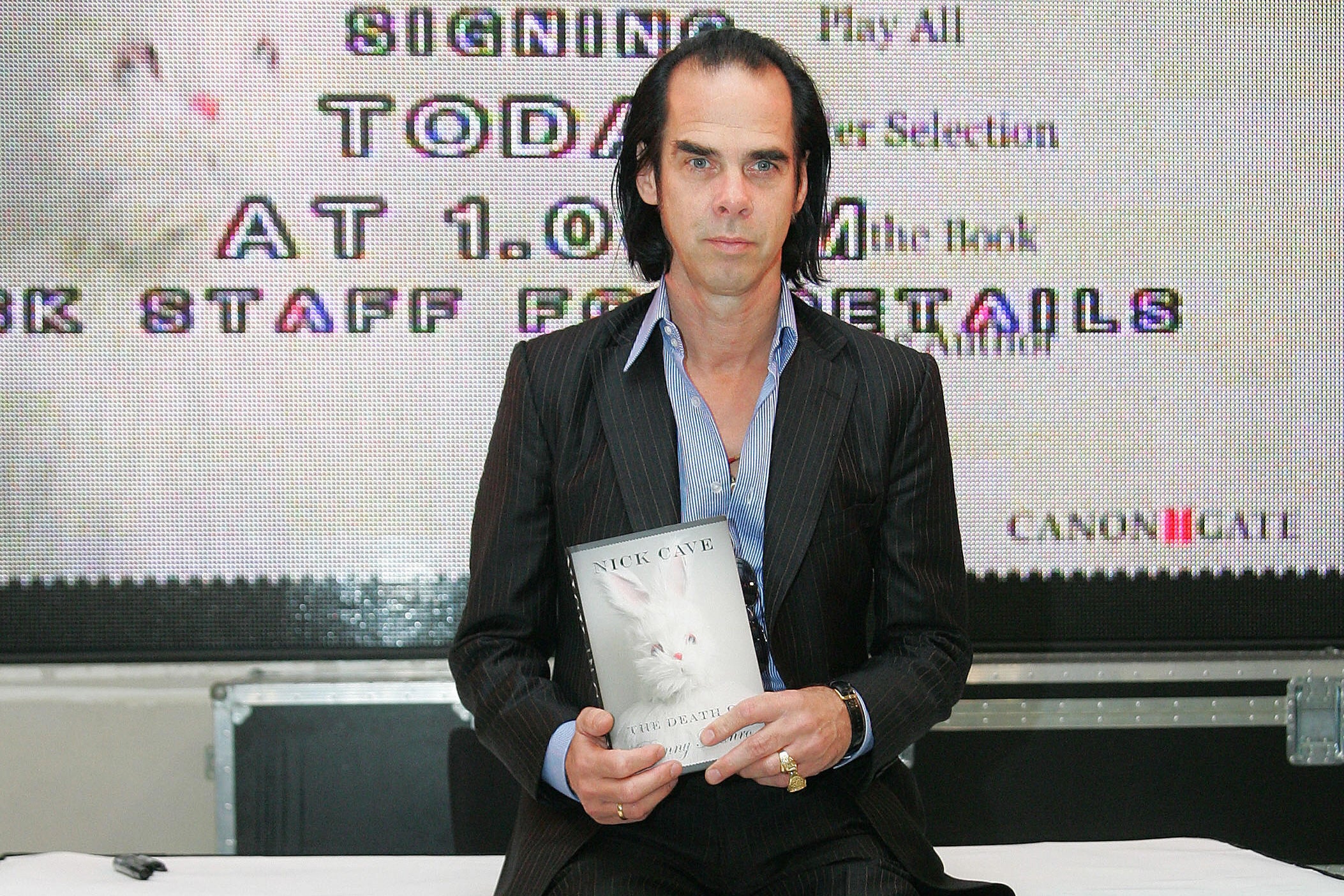

Darnielle’s most serious competition has emerged, like The Mountain Goats, from the world of leftfield rock. Nick Cave’s talent for narrative song found expression in And the Ass Saw the Angel and the exquisitely scurrilous The Death of Bunny Munro. Willie Vlautin, singer in Richmond Fontaine and The Delines, and author of four novels culminating with the very impressive The Free. Colin Meloy, the voice of The Decemberists, has made a splash as a children’s writer.

When I catch up with 50-year-old Darnielle, he is in the middle of writing a song at his home in Durham, North Carolina. Given his reputation for prolificity, this isn’t a huge surprise. The recently re-released Mountain Goats’ classic All Hail West Texas was written and recorded over a few lonely summer days while his wife was away.

Darnielle greets the intervention cheerfully, chatting about new experiments with beats and virtual drummers on Garageband. “They have names like ‘Kyle’, right? Songs have evocative names like AM Gold or B-side. I don’t know why you would pick B-side for your song…”

He is, I suspect, prone to distraction. This partly reflects a restless imagination. Our conversation veers easily from heavy metal band Megadeth’s first three albums to the challenges of parenting two energetic young sons. “Who knows what the family was supposed to be when we all lived in caves? But right now that is the ideal scenario.” There is also the inevitable chatter life under Donald Trump. “What has changed about my daily life? Not much, except my mindset. It’s a psychic weight. Now, there are people who live with things considerably worse than a psychic weight. More people will be hungry under Donald Trump. People losing their benefits wish they had a psychic weight. People are not going to stop coming to shows just because we have a fascist in office. I think ideally most of us don’t want to be living the activist life 24 hours a day. We would prefer to put structures in place so that we can take care of our family, read, listen to music and make love and sleep.’

Darnielle’s song-writing burst is also procrastination pure and simple. He should be getting ready for the Mountain Goats world tour. ‘I am under a lot of stress, and I start writing songs. I know when I am doing that I put anything else on my plate aside. I am not going to do dishes, I am not going to wash clothes, I am not going to get ready. I am going to work on songs because it seems more important and it seems more fun.’

Darnielle is going to need a whole of distracting in 2017. Besides Universal Harvester and more concerts in the UK in October, The Mountain Goats released their new album, Goth, in May. “This is a big working year,” he says before adding. “You can’t complain because people go, I wish I had that problem. It’s hard on the family, but it pays the bills. It’s a nice problem to have.”

Until relatively recently, the very notion of a Mountain Goats world tour would have seemed like a cosmic joke. Darnielle’s novels might have made an almost instant impression, but his band took the best part of 25 years to gain attention of any sort. Dizzying productivity during the early 1990s won The Mountain Goats a small, but already fervent fanbase. While even the most rudimentary recording process could not obscure Darnielle’s way with a melody and vivid lyric, he sold few enough albums, often on limited edition cassettes, to keep Darnielle in his day-job as a psychiatric nurse.

Ironically, the obscurity of this period of sowed the seeds of later adoration. The Mountain Goats’ lo-fi methods, married to Darnielle’s apparent indifference to fame, helped earn them a reputation for integrity and purity. When they eventually entered a proper studio and signed to a proper label, there were doubtless hardcore fans crying sell-out. But this new phase produced a long-awaited breakthrough: The Sunset Tree, a more polished and deeply poignant portrait of Darnielle’s own troubled past. Songs like “Dance Music” detailed the physical abuse doled out by his step-father. Catchy melodies were cut with black comedy: “I am going to make it through this year/if it kills me,” he declaims on “This Year”.

‘It’s the big one so I don’t want to downplay it,’ Darnielle says today. ‘But that was an autobiographical exercise. I was processing that weird grief you have when a person who has done you wrong, but is also important to you has died. It is a definitive record, but I haven’t talked about it that much elsewhere.’

The move to fiction made perfect sense for a writer whose songs possessed wit, poetry and a strong narrative drive: the near-novelistic concept album Tallahassee; the meandering character sketches on the more recent Beat the Champ. Darnielle sees the two forms as related but distinct, and not only because writing fiction is relatively solitary. ‘In any musical endeavour, you get the sense of where you are going. It doesn’t limit you; you can always do a lot of stuff. As soon as you sit down and write fiction, there is always the possibility of exploding everything, on purpose.’

In Universal Harvester, this is visible in running digression that presents alternate histories for a character, often at a pivotal moment in the plot. This is less the result of post-modern emulation than Darnielle wearing his love of 18th century English novelists, naming Daniel Defoe, Laurence Sterne, Samuels Richardson and Butler. ‘They were experimental because the English novel was fairly new, so it is necessarily experimental.’

Beneath the structural fireworks and Blair Witch plotting (disturbing, lo-fi home movies edited onto videotapes of Hollywood films) are characters struggling with grief, loss and basic life decisions. The main protagonist, Jeremy, wonders which job to take, where to live, how to build a relationship with his father, still grieving the death of his wife.

“People describe him as stuck, but maybe Jeremy’s life is just fine. Maybe Jeremy doesn’t have to have epiphanies. Maybe epiphanies are an assumed good. Not to be super conservative, but popular culture sells young people the idea that they have to have big experiences. By the time you’re a teenager you have the idea that you need to have some quasi-traumatic, definitive, epiphanic. I think those are Romantic ideas that bear some interrogation.”

I ask how this applies to Darnielle himself – whose own experience of physical abuse and drug addiction have become part of his own Romantic mythology. “It’s not about me. It’s about kids I used to take care of, right?” he says referring to his former career as a psychiatric nurse. “I’ve had my struggles. The thing I always want to stress is, I have worked with children who would have traded their lives for my young life any day of the week. I know people who'd say: 'I am lucky, my parents were never nice to me; so it was easy for me finally to say, “I want nothing to do with you.”' Whereas for other people it can be more complex. Those are the ones whose grief I am trying to honour if I paint someone who is really messed up.”

It is tempting to trace other autobiographical elements in Universal Harvester. One could read the outsider artist sneaking their work onto videotapes as a warped version of the Mountain Goats recording albums on Panasonic boomboxes. Does the novel reflect any nostalgia for pre-digital, pre-internet times? “I think I enjoyed it more once it became more elusive. Back then I really wanted more people to hear [The Mountain Goats], although I was very obstinate about it. It was a conversation every indie rock artist had in the 1990s: should you record your songs in a better studio with a better producer? Don’t you want to reach the most people?” Darnielle laughs. “You would call those people the devil. That is the very definition of selling out. At the same time, I did want absolutely everybody who might enjoy my stuff to hear it.”

The novel raises similar artistic quandaries when various characters set off in obsessive pursuit of the enigmatic creator of the home movies. Were there further autobiographical hints? Darnielle has inspired comparable devotion, most famously in Lou Reed, Stephen Colbert, and bestselling novelist John Green.

“Hmm. That’s an interesting point that I hadn’t thought of. There’s a lot in the question. As you say, it’s a big honour if people want to seek out stuff from you. But I am always trying to draw the distinction. When people tell me I’m a good person for having done some piece of art that moves them, I always want to stop them. Not only is it a terrible assumption, it’s obviously not true. Lots of really horrible people make really great art which people use to improve their lives and make them feel better and pull themselves away from the brink of ruin.”

Darnielle is neither blind nor immune to the benefits of success: he supports his family by doing what he loves. But nor can he shake a fondness for outsider artists who refuse to court fame of any kind. He mentions Jandek, the pseudonymous folk singer who exists in almost complete secrecy under the guise of Corwood Industries: even a scattering of concerts has only intensified the mystique. “I have a dream of publishing anonymously and seeking no press. Not from any reasons of shame. Just so that the work would be forced to stand on its own two legs. This is a very romantic idea that makes my heart swell. An artist that denies his work even though he knows it’s good; that to me would be a real artist.”

Darnielle’s profile both as a musician and novelist is now high enough that such dreams are impossible. But that doesn’t mean they’re not seductive. “I think what the artist makes can be very special, but the artist himself isn’t. Of course, we know artists who think they are special. They are insufferable and terrible.” He laughs. “You want to stay as far from them as they can.”

‘Universal Harvester’ is published by Scribe, £8.99. ‘Goth’ by The Mountain Goats is out on Merge Records. They tour the UK in October.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks