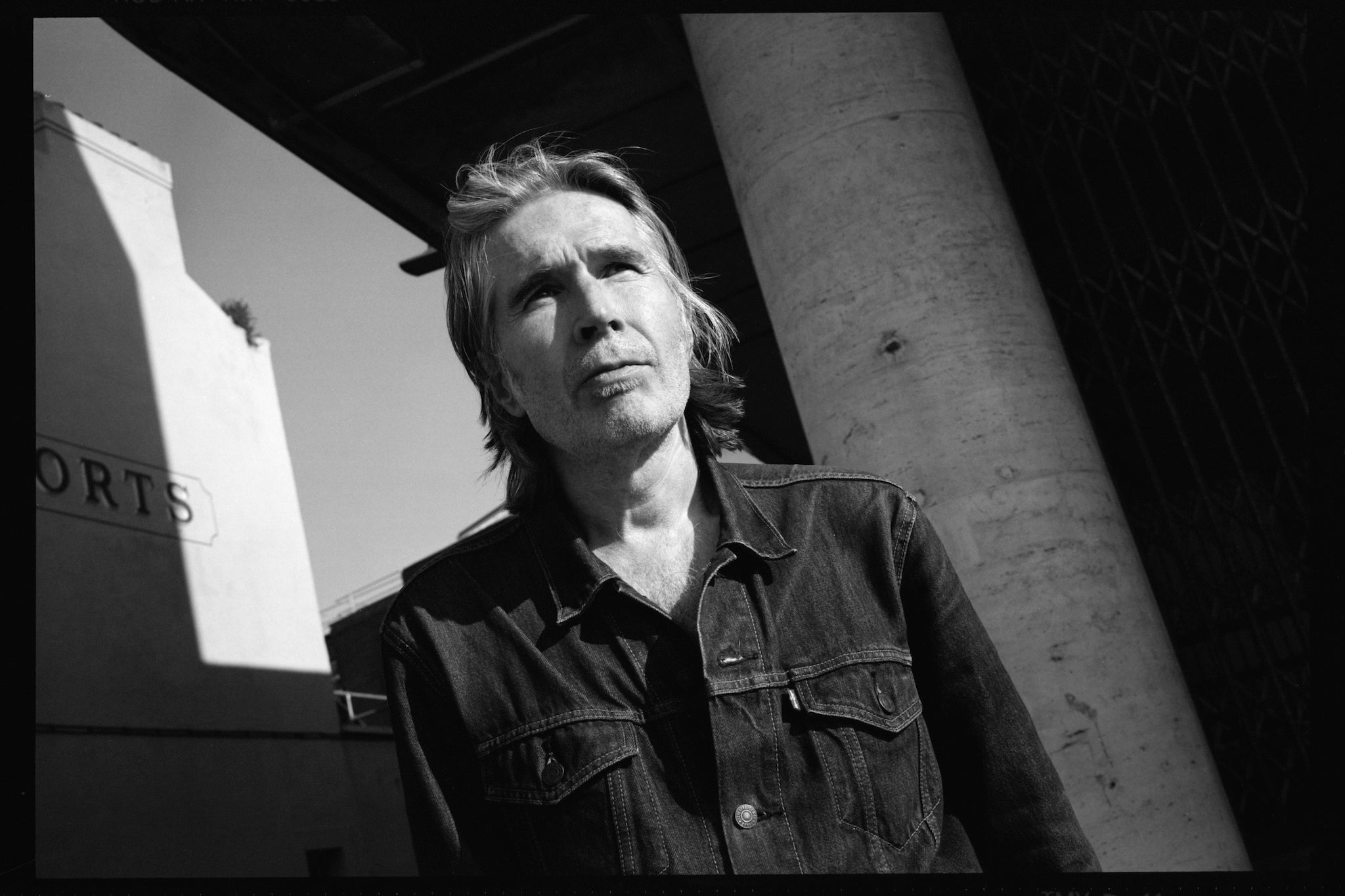

Del Amitri’s Justin Currie: ‘Parkinson’s has highlighted just how arrogant I used to be’

The Scottish rocker delves into his diagnosis with great sensitivity and inky black humour in his new memoir ‘The Tremolo Diaries’. He tells Nick Duerden about living with the disease and the upside of tragedy

In January 2022, Justin Currie, the singer with Scottish band Del Amitri, attended an appointment at Glasgow’s Queen Elizabeth University Hospital on the suspicion that he had Parkinson’s. There, the neurologist explained that a brain scan might not find anything, and that diagnosis could take up to a full year. Nevertheless, he was certain it was Parkinson’s.

“How can you tell?” Currie asked. The doctor instructed him to rest his arms by his side, where his right hand was trembling gently at his hip, as it had been doing for some time. “Now lift your hands to shoulder height.” When Currie did this, the tremor stopped. “That’s how.”

The singer left the hospital officially a sick man. He was 57 years old. In his new memoir, The Tremolo Diaries, he writes that the tremor feels “as if your own shadow has leapt from the ground and buried itself within you. This shadow has malevolent intent. He may share my shape, but now we are combined. It’s a fight to find out who has the most valid claim.”

Few among us would react well to confirmation of a life-changing brain disease, one whose progression would ultimately hamper the ability to keep working, but Currie was determined to plough on. His band had a tour booked, which he intended to fulfil. Initially, then, he told no one about his illness bar those closest to him – with the exception of his mother. “She was in her eighties, and she’d have been devastated.”

Surely she noticed, I say; Parkinson’s isn’t easy to hide. “I think she did, yes, but she just thought I was drinking too much. And to be honest, I’d rather she thought that than Parkinson’s. Anyway,” he deadpans, “she died not long after, rather conveniently.”

Currie has been the frontman of Del Amitri since they formed in the early Eighties. A much-loved band with a modest but loyal following, they first came to commercial prominence in 1989 with Waking Hours, a beautifully eloquent album of kitchen sink dramas woven into honeyed guitar melodies, one of which, “Nothing Ever Happens”, gave them their first hit single.

By the 1990s, Del Amitri – replete with a wardrobe of denim, often double-denim – were channelling the classic US band the Eagles, which in part helped them break America. Their jolly 1995 single “Roll to Me” became a staple of US radio, where it played endlessly. “That song has paid my mortgage for the past 30 years,” Currie says with a happy shrug.

A few months after that fateful hospital appointment in 2022, Del Amitri did indeed fulfil their already-booked tour, playing third on the bill to Canadian outfit Barenaked Ladies and US balladeers Semisonic in venues across America. With an early stage time, they often performed to half-filled venues, most of the audience still parking their cars outside. Hardly The Rolling Stones at Shea Stadium or Oasis at Maine Road, true, but then such is the life of your average band, playing on the kind of tour that employs no personal masseur and requires no private jet.

“It can get pretty boring,” Currie notes. To keep himself occupied, he began to write his book, something he’d never have considered had he not become sick. “I suppose I knew that it gave my story an edge,” he tells me over Zoom from his house in Glasgow, “but I was worried that the book would be full of moaning. People my age tend to moan a lot, don’t they? I didn’t want it to come over as one big whinge.”

Despite reservations, he kept writing, agonising as he typed. Consequently, there is no swaggering ego within The Tremolo Diaries. Instead, it is almost heroically self-deprecating. At one point, perhaps while measuring himself against the likes of Mick Jagger and Liam Gallagher, he concludes: “I might be a mediocrity.” Elsewhere, he finds himself in an airport awaiting a flight, “contemplating the tremendous wreck of my recent life”. When he sent the book to his publisher, he says, “I was terrified. I thought it was so f***ing boring.” It isn’t.

The Tremolo Diaries: Life on the Road and Other Diseases might just be the finest music memoir of recent years. It’s certainly the most wincingly honest. Where the majority of such books serve largely to perpetuate the rock-star stereotype – Keith Richards’s Life (2010), for example, told a preposterously entertaining tale of sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll, while Robbie Williams’s Feel (2004) did likewise but also offered a fascinating insight into his struggles with his mental health – Currie’s lifts the lid on a more treadmill existence.

I’ve done everything I was ever meant to do, so I should count myself lucky

Like so many bands, Del Amitri were never particularly cool, or particularly big. They had a few hits that enabled them to sustain an enduring career, but they do not now live in mansions, or own a fleet of Lamborghinis. Instead, they keep writing songs, which they play live to a diminishing hard core of fans, then write more songs to play live, and repeat the process ad infinitum as they get steadily older and greyer and increasingly deaf. It’s a living.

Currie freely admits that playing to mostly uninterested Americans on farmland near Minnesota when you are almost 60 years old and in poor health isn’t exactly what he thought he was signing up for all those years ago. His days are spent browsing art galleries and museums, and looking for the perfect burrito.

When, late in the book, the band accept an invitation to play a show in the Middle East, he worries that “we are pumping obscene amounts of carbon into the air to frolic in an absolute monarchy. I could say I was railroaded into doing this show, but I’m here and I’m guilty of all charges: hypocrisy, greed and moral turpitude. There’s a prayer room next to the toilets. Perhaps I should ask for forgiveness.”

This could all make for bleak reading – and indeed, it occasionally does. Summoning a Beckettian spirit of “I can’t go on. I’ll go on,” he writes: “My fire is slowly going out. Let it all die.” But Currie, unlike many comparably accomplished lyricists, reveals himself to be a born prose stylist. He can’t produce a dull sentence, and has a novelist’s eye for detail. On, for example, the necessities of abstaining from alcohol in order to manage the symptoms of Parkinson’s while on tour, he observes: “Doing all this sober is like being forced to read your favourite book without punctuation.”

What makes it quite so compelling is its account of just how cursorily cruel life can sometimes get. Just a few months after his diagnosis, and his mother’s death, Currie’s partner of many years suffered a massive stroke. She now resides in a care home, requiring constant supervision.

“All of these things on their own I’d have been quite able to deal with, I think, but the three of them happening at once were... if not quite overwhelming, then very certainly whelming,” he sighs. “I was now visiting my partner in hospital twice a day, while shaking like a leaf, and thinking to myself, ‘What the hell is going on?’”

I ask him how he is doing today, then apologise for sounding quite so trite. “It’s a strange disease, Parkinson’s. Sometimes, you can wake up and forget you have it altogether. Right now, I do feel like I’m in a honeymoon period, where I’m pretty much fully functioning,” he says. “I take my pills, then I wait for the pills to take effect, but everything still requires a lot of concentration.”

He is nonetheless adamant that the band will continue for as long as he himself is able to, even though the illness has exerted a toll on his songwriting abilities. “I usually like having nothing to do, as I find that quite good for writing songs and motivating myself. But now, having nothing to do is not great, because you just tend to dwell on the fact that you feel weird, and that something kind of rubbish is happening,” he says.

He’d rather not contemplate what happens after his band comes to an end, at least not yet. “But I try to remind myself that I have a lot to feel grateful for. If this had happened when I was 35, I’d have been devastated. But I’ve done everything I was ever meant to do. So I should probably count myself lucky.”

One upside to all this, he suggests, is that he now feels more empathy for others than he ever did previously. “Parkinson’s has highlighted just what an arrogant motherf***er I used to be. I was very intolerant of people’s weakness before – if they were ill, or going through a domestic crisis,” he admits. “I just always focused on the work, and on myself, this ubermensch who played five-a-side football every week, and got to play on a stage every night. I just didn’t care. I was an absolute c***, to be honest. I’m slightly less of one now.”

He pauses for a moment, and looks off into the middle distance. “You feel a real kinship with all sorts of people when you become a member of the Great Unwell,” he says.

‘The Tremolo Diaries: Life on the Road and Other Diseases’ by Justin Currie is published on 28 August by New Modern

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks