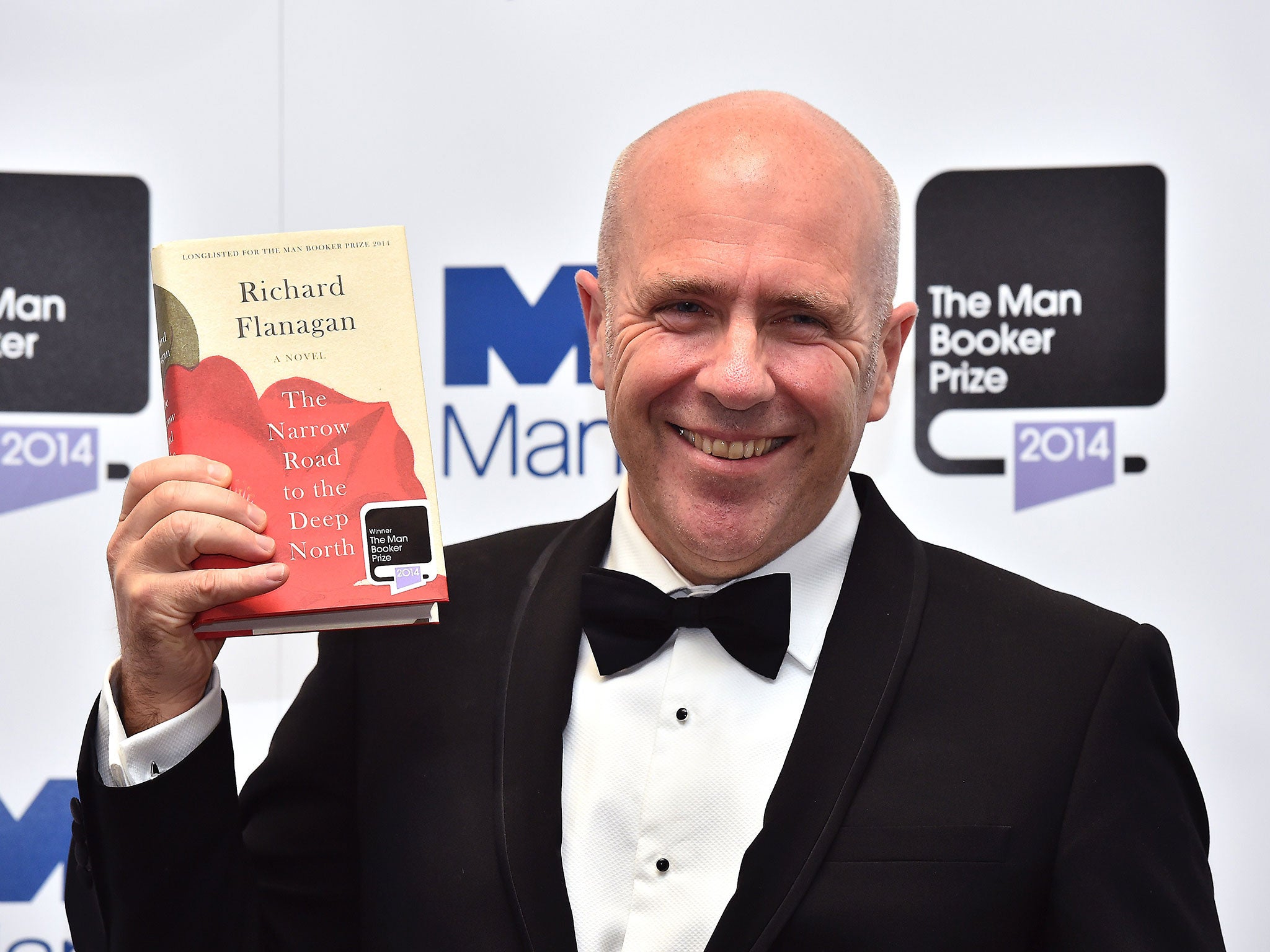

Man Booker Prize winner Richard Flanagan: 'The Narrow Road to the Deep North was a novel I never wanted to write'

Richard Flanagan won the Man Booker Prize for a tale inspired by his father's experiences in a Japanese PoW camp

It is the morning after the late, jubilant night before and Richard Flanagan, like so many previous Man Booker winners, has not had much sleep. The victory was nothing less than a shock. "Just as I was beginning to enjoy the dinner, have a few drinks… my name was being called out."

Flanagan, 53, from Tasmania, who is married with three daughters, got home well after 2am after tackling the last of the media, to tackle the first of several hundred well-wishing texts. Unlike some Booker winners, Flanagan feels only gratitude towards his prize-givers. There is no sniping that it's all just "posh bingo", nor about belated recognition, nor about how the Americans should never have been allowed into Booker's sacred circle this year (fellow antipodean and twice Booker-winner Peter Carey lodged his complaint most recently).

The bookie's outsider, Flanagan has absolutely no complaints. There is by turns intensity, easy antipodean charm and generosity, particularly towards his fellow shorlistees. In his winning speech, he declared the prize "ours" and he stands by his admiration for his five "formidable" contenders this morning. There is even a nod to the bookies for their odds: his 95-year-old mother bet her week's pension on him, so they'll be paying out handsomely today.

His sixth novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, is heart-wrenching and profoundly personal. Set in a Japanese PoW camp on the Burma Death Railway, its inspiration, in part, arose from a place of love, albeit considerable pain, too. It is dedicated to his father – prisoner 335 – who survived a gruelling internment on "the line" in a Japanese PoW camp where 14,000 died, though the narrative is driven as much by the central love story as its tortured counterpoint of war.

The anguish that Flanagan felt over the PoW experience, and the need for emotional catharsis, was not solely rooted in his father's trauma. (His father in a tragic twist of fate, died aged 98, on the day the novel was completed). Flanagan also drew on his own anguish: "I felt I carried something within me as a consequence of growing up as a child of the death railway. People come back from cosmic trauma but the wound does not end with them. It passes on to others.

"I didn't want to write this book but in the end I couldn't escape it. If I didn't write it, I'm not sure I could write another book. I had to deal with things which could become a stumbling block within me. I had to define them."

It wasn't an easy process. It took him 12 years and five different drafts ("one is haiku form, one as an Odyssean journey by a PoW... all terrible"), and a period of solitary confinement. "I lived by myself in a shack on an island off Tasmania for the last six months of the novel."

In an interview this week, Carey hailed Flanagan's book as a turning point in Australian fiction. Prior to this, he said, writers of his generation – those who took part in the anti-Vietnam protests of the 1960s – had struggled to deal with this aspect of Australia's war (and Japan's part in it) in fiction. Did Flanagan hesitate to go there? "It's difficult material. It's so easy to do it badly. Peter Carey's comments were so generous, but revealing to me, because I haven't thought of it that way."

While the novel's starting point was his father's story, it was extended upon and elaborated fictionally through his protagonist, Dorrigo Evans, an army surgeon who is indelibly touched – and damaged – by war and also by love for Amy, his uncle's young wife.

Flanagan spent a lot of time with his father before he died, talking about the finer details of his PoW experience, too. "I didn't interrogate him much. I was interested in the small things – the smell of rotting skin, what sour rice tastes like for breakfast, the feel of the mud."

Flanagan's early life was a fairly unusual one for an author in the making. His grandparents were illiterate, his uncle lived in a cave where he snared possums for a living and he, with his five siblings, grew up in a house in a mining town with one small cabinet of books to their name.

It was his father again who provided early inspiration for Flanagan, the young boy. "He was a state primary school teacher. He grew up incredibly poor and he was the only one to get an education – he got to high school. From him, I got the sense that words could be utterly oppressive if you didn't get them. But if you had the capacity for the written word, they were magical and liberating. He committed a lot of poetry to memory – Shelley, Bryon, Kipling – he would just break into it whenever he chose. I'd check afterwards and he was always word-perfect. In the end, he conceived the world as a poem."

The Narrow Road to the Deep North is brimming with poetry, both in its prose, and the verses that Dorrigo quotes by heart. "I love words because you can only live one life but in a novel, you can live a thousand, you contain multitudes," says Flanagan.

Flanagan's book does not just trace Dorrigo's inner world, but gives his Japanese "torturers" and camp commanders a voice, and a subjectivity, that incorporates humanity and tenderness, rather than a black-and-white evil. As part of his research, he tracked down a commander at his father's camp, and spoke to him at length, calling him a "gentle, gracious old man". Again, this might be related back to his father. "He brought us up not to hate, never to judge. He had no hate [for the Japanese]. What my father took out of the camps was this extraordinary sense that everything is an illusion except for what you are like with other people, and to never think other people are in any way lesser than you."

The novel's love story – raw, overwhelming and ultimately doomed – has been compared to Doctor Zhivago, Madame Bovary and Birdsong. It, too, was partly inspired by real events. "In 2002, I was at Sydney Harbour Bridge, and I remembered a story about a Latvian man who lived in our small town when I was growing up. He had been caught up in the tidal movements during the war. He made it back to his village, which had been razed to the ground, and was told his wife had died. He refused to believe it and searched for two years for her.

"In the end, he accepted she was dead. He emigrated to Australia, married and had a family. Then, in 1957, he went to Sydney and saw her in a crowd, with a child in each hand. He had just a few moments to decide if he would acknowledge her."

The return of this vivid memory inspired Flanagan to go to the nearest pub in Sydney Harbour and write it all down, rapidly, on beer coasters with a Biro. "It was the first thing I wrote for this novel. I wrote five novels trying to get to this [version]. Finally, I returned to the bear coasters, and this love story."

He left school at 16 to return to education at the University of Tasmania and then to Oxford as a Rhodes scholar ("let's not talk about that, it was an unhappy time"). He wrote four books of non-fiction before embarking on a full-time career as a novelist 21 years ago. He has won the Commonwealth Writers' prize, worked with the film director Baz Luhrmann on the screenplay of his epic Australia, and won Australia's foremost literary prizes. So it's a surprise when he reveals, after finishing this latest novel, that he seriously considered working in north-west Australia's mines to pay the bills in between books.

"We had run out of money, that's all. An unskilled middle-aged man can work in the mines, and it pays well… Writing novels has changed in the last five years. It's very difficult. I'm a successful novelist and I've been a lucky one so I don't want to cry the poor mouth. Writing has never been easy. Look at the history of literature and you find the history of beauty on the one hand, and the IOUs on the other."

His next book is a contemporary novel about a ghost writer, writing the memoir of a conman, and it has some echoes of his own lived experience: "I've ghost-written the memoirs of a conman." It will be published next year, if the welcome distraction of post-Booker publicity doesn't knock him off course. "It's my intention to go back to Tasmania and pull down the shutters and carry on writing."

But for now, he's riding the tide, and happy to do so. What would his father think of his achievement, I ask him. Immediately his eyes well up and his voice thickens. "I can't allow myself to go there," he says, though later, with regained composure, he ventures an answer.

"He was an ordinary man with an extraordinary life…. He would be happy about this. But he would ultimately see it as unimportant. What mattered to him was how I am with my family and friends."

'The Narrow Road to the Deep North' is published by Chatto & Windus (£16.99)

The first paragraph from 'The Narrow Road to the Deep North'

Why at the beginning of things is there always light? Dorrigo Evans' earliest memories were of sun flooding a church hall in which he sat with his mother and grand-mother. A wooden church hall. Blinding light and him toddling back and forth, in and out of its transcendent welcome, into the arms of women. Women who loved him. Like entering the sea and returning to the beach. Over and over.

Bless you, his mother says as she holds him and lets him go. Bless you, boy.

That must have been 1915 or 1916. He would have been one or two. Shadows came later in the form of a forearm rising up, its black outline leaping in the greasy light of a kerosene lantern. Jackie Maguire was sitting in the Evanses' small dark kitchen, crying. No one cried then, except babies. Jackie Maguire was an old man, maybe forty, perhaps older, and he was trying to brush the tears away from his pockmarked face with the back of his hand. Or was it with his fingers?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks