The all-Islamic super-heroes: Muslim children love 'The 99' comics, but hardliners loathe their creator - whose trial for heresy is looming

Naif Al-Mutawa has detractors in both America and the Arab world, though for opposing reasons – to US conservatives, he is a terrorist; to Islamist Arabs, he is a heretic. He talks to Arifa Akbar

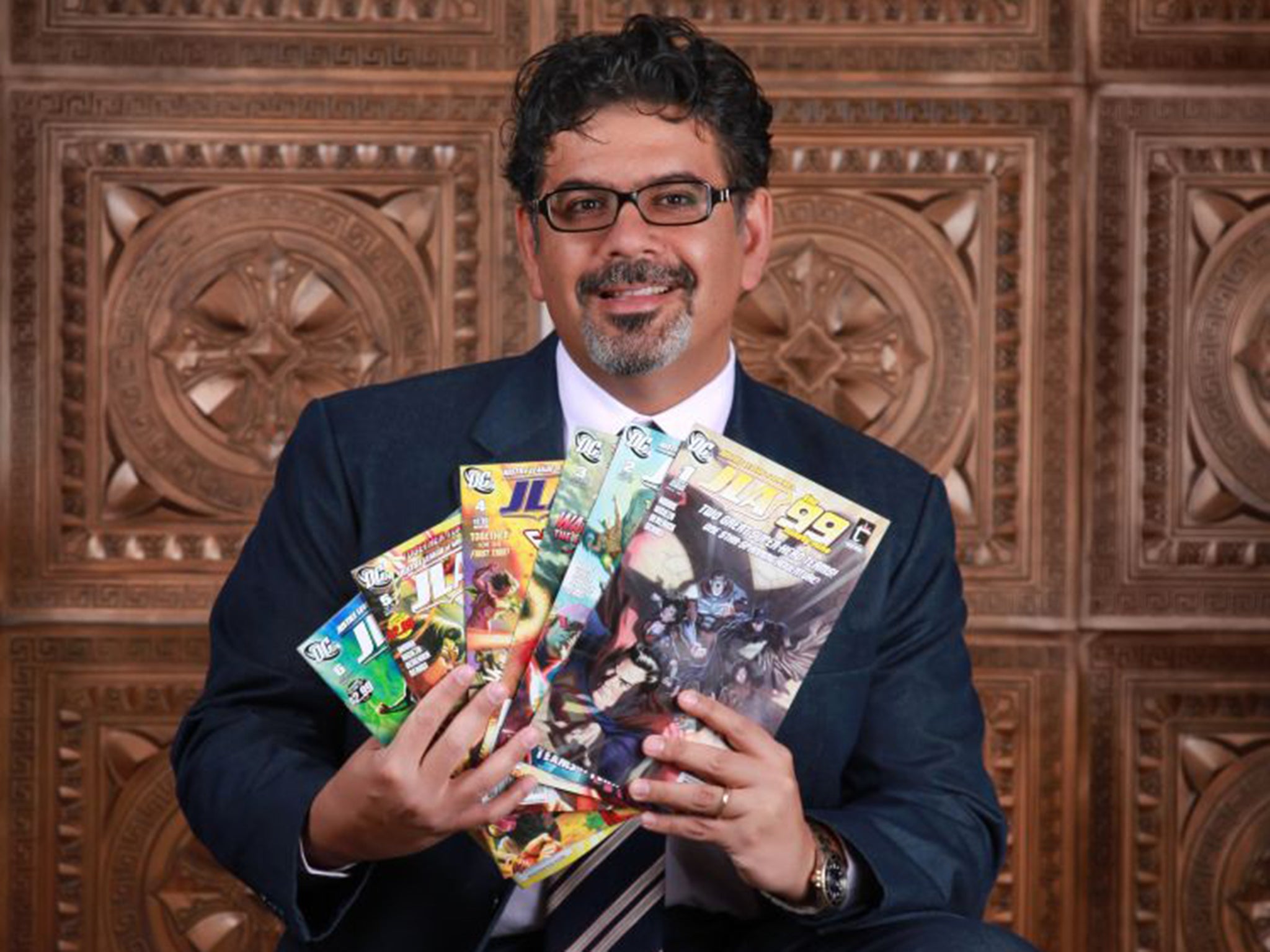

Just over a decade ago, Naif Al-Mutawa had a lightbulb moment. Sitting in the back of a London taxi, he decided not to follow his chosen field of study – despite two psychology degrees and a freshly acquired doctorate – but to create comic books instead.

Enter The 99. Drawing on the strong-men and -women archetypes in the Marvel and DC universes, and now in their 10th year, Al-Mutawa's comic books have their own fleet of superheroes: an all-Islamic cast gifted with special powers embodying the 99 attributes of Allah – such as generosity, wisdom and strength – that are named in the Koran.

These paragons are in perpetual battle with Rughal, an Osama bin Laden-inspired villain who could just as well be the face of Isis or "any other self-styled messiah" in our post-al-Qaeda world. And each superhero, from a different part of the world, is a protégé of their mentor, Dr Razwi, who like Dr Mutawa himself, is a trained clinical psychologist, fashioned from the "best" imaginary version of himself.

Launched in 2006 – first in Kuwait after the approval of the state's Ministry of Information, then in America and the rest of the world – The 99 was hailed as an exemplary model of inter-faith peace and tolerance by Barack Obama, and Dr Mutawa was invited to give two TED talks. He has since been featured in Forbes magazine, won prizes in the Gulf region and gained the approval of the Saudi state.

However, for some he is a defender not of peace but of profanity: ironically, he has hardline detractors in both America and the Arab world, though they hate him for opposing reasons. To US conservatives, he is a terrorist and a pawn of hardline Islam; to Islamist Arabs, he is a heretic and a pawn of the liberal West.

Both camps have, in the past decade, warned of the dangers of his creation and called for it to be banned. America's God-squad even created enough moral panic about "radicalising children" to halt a Hollywood adaptation of The 99 – produced by Endemol and scripted by the teams behind Star Wars, X-Men and Spider-Man – from being shown in US cinemas or on its network television. (This leads Al-Mutawa to joke: "I have a fatwa from Fox News!")

But now there is a more serious threat from within his home country. While the Kuwaiti government has endorsed his work, not everyone agrees with its message. In the past year, a Twitter campaign has accused him of being a blasphemer who should be brought to trial; and a legal case has been launched against him – not by the state, but by a fellow Kuwaiti suing him for heresy. (If he loses – and he firmly believes he won't – he could face a prison sentence.)

Since then, Al-Mutawa has received a hail of abuse and death threats. culminating in an ironic sequence of events: "Shortly before New Year 2014, I received an email informing me that The 99 had won in the media category of the Islamic Economy Awards [in Dubai]. A few days later, I received an email from my lawyer updating me on the case lodged against me in Kuwait for heresy and insulting religion through The 99. This is the same book President Obama, Sheikh Mohammed, even His Highness the Emir of Kuwait, publicly endorsed as being a bastion of tolerance."

How to negotiate this impossible position of being both hero and villain to two usually opposed camps? Judging from appearances, Al-Mutawa is not letting his detractors win. At the age of 43, and a father of five young boys, he has an incorrigibly Tigger-ish quality. Meeting him at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature in Dubai, he is warm and loquacious to the legion of fans who mob him – parents and children alike, from India, America, Britain and the host country's multi-faith ex-pat community. He will admit, though, that the past year has taken its toll. He was particularly shaken by the chilling Twitter hashtag, #whowillkillDrNaif, that drummed up hate against him last summer. He is frustrated to be summoned to court later this month – on 26 March – not least because the prosecution managed to secure a fatwa from the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia, who called his work "evil".

This is another perplexing aspect of his case: six years ago, the Saudi Ministry of Information approved the comics, which were openly sold in the country. Dr Mutawa has an answer for this: a fatwa depends heavily on the questions you ask, and if those are skewed, then the questioner is responsible for the skewing of the answer.

"The question asked of the Mufti was couched in negatives and mis-statements," he says, "perhaps purposefully and maliciously, perhaps out of ignorance."

Today Al-Mutawa takes his religion seriously, but there was a time when Islam neither appealed to him in popular literature nor in life. As a clever, inquisitive teenager, he rejected its messages: "It seemed black-and-white and I didn't like black-and-white."

Only after a conversation with an imam who was studying at Harvard Divinity School (he himself was reading psychology at Long Island University, followed by an MBA at Columbia) did he begin to see the religion's nuances and find himself drawn back.

What led him to create The 99 was the revelation, as simple as it seems now, that the tenets of the Koran were universal and humane. But there was also the political element: 9/11 had happened, Islamist terror had irrevocably left its stain across the world, and in return the world had begun to question whether the religion could be compatible with the Enlightenment values of the West.

After the Danish cartoon controversy of 2005-6, Al-Mutawa found his ambition even more relevant, if highly-charged: "It was something I began for my creative side but also for my 'fed-up Muslim' side. People kept bastardising Islam in order to go to war. I wanted to take the central values of my faith, which I believe are human values, and use them creatively. I wanted to say, 'This is Islam and it's no different from your values'."

Thus, in one of his TED talks, he claims he chose the medium of children's cartoons in order to prevent a future of radicalised young men and women: they were created to "fight for the hearts and minds of the kids who have been taught to hate". However, he points out that the idea's roots are not entirely original. There is a long tradition of comic-book characters whose back-stories lie in theology, he says; they just hadn't penetrated Islamic culture before.

"One of the people I met in my research was Neal Adams [who helped to create the defining imagery of such DC Comical characters as Batman and Superman] and he has spoken of the long history of comics and religion. For example, Captain Marvel says, 'Shazam!', which is an acronym for the six Greek gods from whom he gets his magical powers – Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles and Mercury. Superman has a Moses link. [Its creators were Jewish, and some scholars have suggested that the mini-rocket in which the baby Superman left the planet Krypton has its parallel in Moses' basket in the bullrushes.] It got me thinking... "

And drawing. The first episode of The 99 begins in 1258, with the Siege of Baghdad. "Generation after generation of Arabs know this story. It is pivotal to our history, when the Mongols invaded and destroyed the Grand Library." (However, in this version, its countless precious books are saved from being dumped in the River Tigris.) As for the characters, they first appear in the form of stones scattered across the world. When they acquire their powers, they initially use themfor self-interest, but, says Al-Mutawa: "When you use your powers in this way, you get taken advantage of by people who want to exploit these powers."

There is also what Al-Mutawa calls a "self-updating mechanism" within The 99. As he explains it: "Everyone believes the Koran is for all time and all place. Some people believe that means the original interpretation from ancient history is still relevant today – which I don't believe. There there's the group that thinks it is a living, breathing document. The 'updating mechanism' captures that. And Rughal does not want the updating to happen."

Given the context, Al-Mutawa was also aware there was a risk that his depiction of heroism among bearded Eastern men and head-scarfed women would be interpreted as "jihadi" or extremist. And that, he says, was why he made the moral behind The 99 so clear.

Religion has always been prone to misappropriation, he thinks – more so now than ever in the case of Islam – but there are also Western examples of "bad" people subverting "good" books. "I always use the example of The Catcher in the Rye," says Al-Mutawa. "JD Salinger's novel of teen alienation had a lasting influence on Mark Chapman, who assassinated John Lennon in 1980, and who wanted to change his name to Holden Caulfield; it was also found in John Hinckley's hotel room after his failed attempt on Ronald Reagan's life a year later. Is this a dangerous text, or are these two deranged readings of it?"

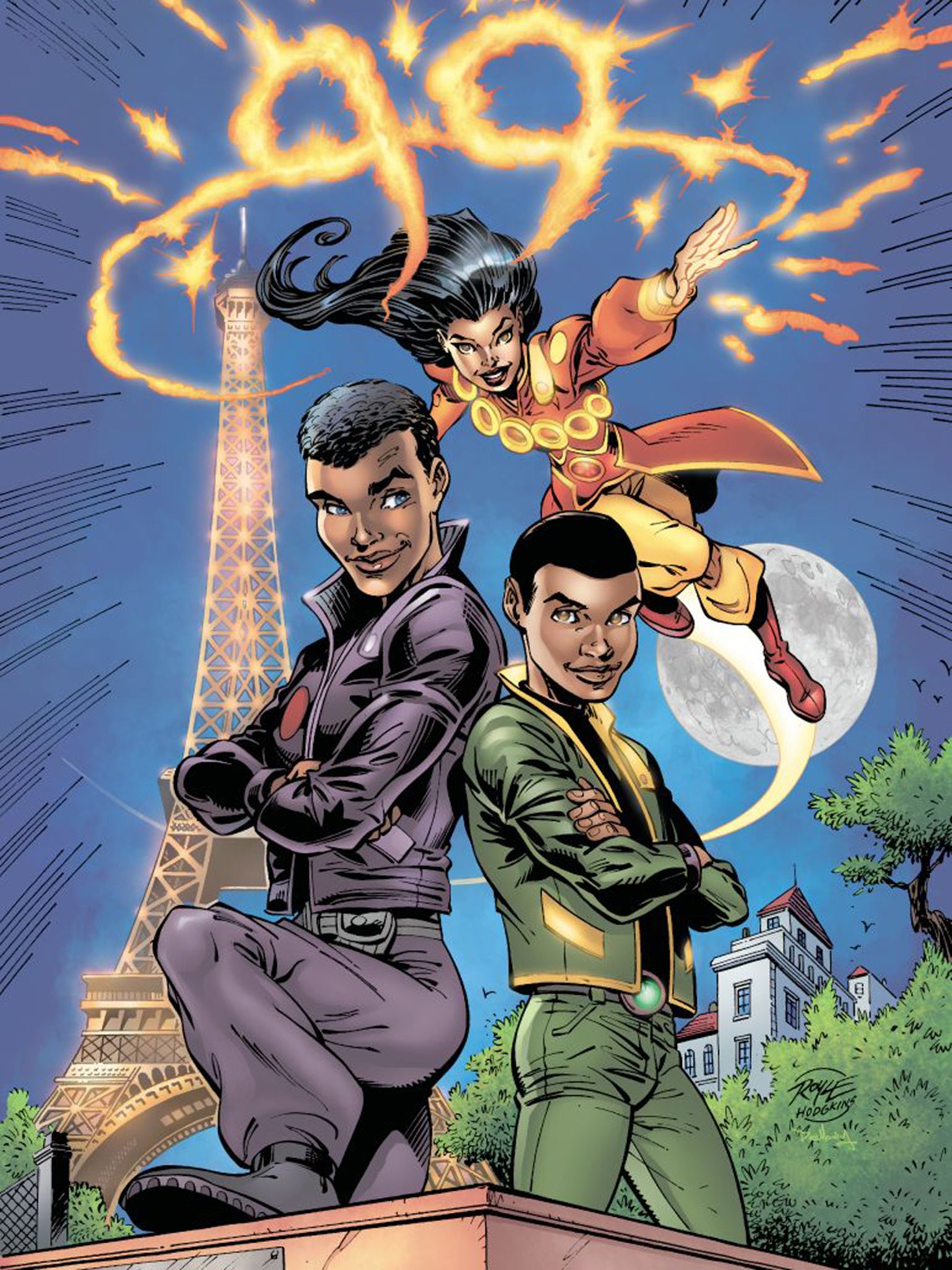

Aside from the underlying messages in his stories, he admits he had a lot of fun creating his characters: his is a rainbow-nation of superheroes – from Iran, Yemen, Ghana and Hungary, among others – who come together despite racial and cultural difference. The Iranian superhero plays with fire. More mischievously, the French female superhero wears a burqa (which is banned in France); a Yemeni character is based on his Saudi-Yemeni wife, Rola Banaja; and a bully from his childhood appears in one storyline: "I was an overweight kid and this cousin with whom I have since made peace would bully me, so I put him in there."

When Obama made his seminal speech in Cairo in June 2009, reaching out to the Muslim world, Al-Mutawa decided to mark that moment in comic-book terms by having The 99 work with superheroes from the West. A DC Comics crossover came out in which his Muslim characters met and saved the world, along with Superman, Wonder Woman and the rest of the gang. And since then, one of the most satisfactory outcomes has been that the American publishers have gone on to create their own Muslim superheroes. In 2013, Marvel brought out Ms Marvel, a Pakistani superheroine whose "real" name is Kamala Khan, while DC introduced Nightrunner, a French-Algerian sort-of Batman, and Simon Baz, an Arab-American in the Green Lantern Corps. What's more, the Hollywood adaptation of The 99 was finally released and has been seen around the world, either in cinemas or as a TV show.

He feels due pride in his creation and its legacy. "In a world where Muslims were just evil characters, these offer another way of seeing Muslims. There will always be psychopaths who misinterpret religion for their own gain, but the only real way to combat the extremism is through arts and culture – appealing to the young through stories."

Yet the fatwa and the court case still loom. Reading the comics and speaking to the mild-mannered Al-Mutawa, it is perplexing why, so many years after his sparky invention, he should be targeted now. Why does he think The 99 is touching such a nerve? He shrugs. Who knows? The message is there, clear and positive. "I grew up being bullied," he adds. "It's not comfortable but it's familiar."

All the while, irrespective of the furore, children around the world continue to fall in love with his intrepid Islamic superheroes. And that, he says, is the best story of all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks