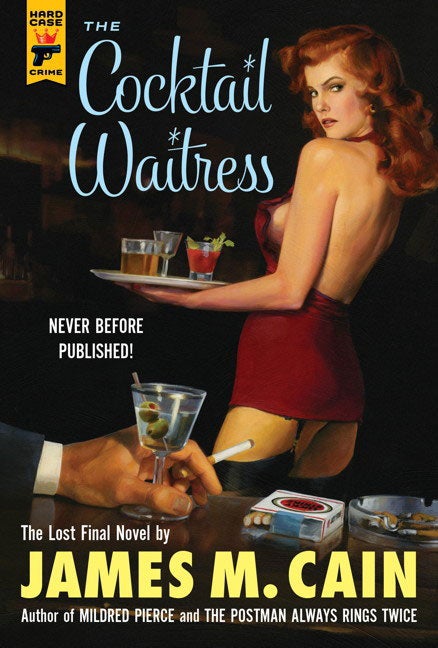

The discovery of James M. Cain's lost novel The Cocktail Waitress

Charles Ardai describes the discovery of an unpublished work by the great American crime writer

When people talk about James M. Cain these days, it tends to be in reverential tones - he’s earned a spot as one of the ‘big three,’ the giants of hardboiled crime fiction whose works are considered classics (the other two being Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler). Cain’s books have been taught in universities - even Harvard. People write dissertations about them.

But back when Cain started publishing his lean, tough novels in the 1930s and 40s – and even on into the 50s and 60s – he was seen very differently: as a dabbler in sin and scandal, a purveyor of the lurid and the low.

The Saturday Review of Literature famously said, “No one has ever stopped reading in the middle of one of Jim Cain’s books,” a line that’s been quoted on several generations of Cain paperbacks, but it was a backhanded compliment, acknowledging his books’ explosive popularity with readers more than their quality. Time magazine, meanwhile, sneeringly called his books “carnal and criminal” and their author a “hoary old sensation-monger.”

They were made into movies. One, Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity, scored a Best Picture nomination upon release and has since been named one of the 100 best American films of all time by the American Film Institute.

Cain’s books also sold millions of copies and were translated into eighteen or nineteen languages. All of which just goes to show how little critics’ opinions count for if you’ve got readers in the palm of your hand (which, god knows, Cain did), and if your books are actually good (which, god knows, Cain’s are).

But it would be a mistake to completely ignore the reception Cain got in his heyday, because it tells you something about what it was Cain was doing. The fact is that Cain was a scandalous, shocking writer – even a dangerous one, insofar as any novelist can be called dangerous.

He shook up the social order of his day, delighting in pricking over-inflated balloons and watching them go pop. He brought matters into popular fiction that weren’t the subject of polite conversation back then (some still aren’t even now) – adultery, incest, depravity of all stripes, sexuality of all flavors. He had an underage temptress stealing her mother’s lover a decade before Lolita.

He had murders so brutal, so visceral, that even reading them today your gut twists. His books were banned. Is there any wonder that he attracted readers by the carload, or that they read his books breathlessly to the last page?

But unlike a mere sensationalist, Cain put this shocking material to work in the service of larger aims: showing us life as it is lived, language as it is spoken; the dreams and hungers and despairs of ordinary people in dire situations; the impact on the human soul of crisis and the ability of the human animal to give up its humanity under duress.

Cain’s characters sweat, and have reason to. And when you read about them, he makes you sweat alongside them. You want to know what it feels like to be trapped in a loveless marriage, yearning hopelessly for something better and grabbing desperately at a way out even if it’s cruel and repellent and doomed? Read The Postman Always Rings Twice. If you feel you need a shower afterwards, that’s to its credit, not a criticism.

Which brings us to The Cocktail Waitress, Cain’s final novel, and one that shows us that even at the end Cain still had the ability to disturb, to trouble, to shock.

In 1975, James M. Cain was 83 years old; in two more years he’d be dead. His star, which had risen so meteorically in the 30s and 40s had fallen just as meteorically. He’d moved back east from Hollywood to Hyattsville, Maryland, where he suffered from a painful and debilitating heart condition – angina. He was an old man and getting older, in failing health and aware of it. But he was still a writer, goddam it, and every day he put pen to paper and the words flowed.

Some of these late efforts were attempts to branch out into other areas of fiction – a historical novel, a children’s book. But at the very end, when he knew he most likely had only one more book in him, he decided to go back to his roots and write a James M. Cain novel again.

Clearly he put elements from his own life into the book – the Hyattsville setting, Earl K. White’s angina, the nitroglycerine pills White carries (Cain carried them, too). He also returned to themes from his earliest and most successful books. From Postman and Double Indemnity there’s the idea of a young, attractive woman, married to an unattractive but well-heeled older man, who meets a new man, young and handsome, who’s ultimately implicated in the husband’s death. From Mildred Pierce he took the premise of a female protagonist in severe economic straits, just getting out of a bad marriage, who has to take a degrading job as a waitress in order to provide for her child. The result of combining these elements is a classic Cain femme fatale story that’s told for once from the femme fatale’s point of view.

Of course, no femme fatale thinks she is one, or admits it if she does. Which presents an interesting problem for a book told in the first person. In fact, Cain began writing The Cocktail Waitress in the third person, along the lines of Mildred Pierce, and got more than one hundred pages into the manuscript before abandoning the approach and rewriting the whole thing in his patented intimate first-person style. It was a good decision. The book springs to life when we see events through Joan Medford’s eyes and hear them in her voice. But putting the story into Joan’s voice means we hear only what Joan wants us to hear. And as she perceives things, or at least as she tells them, she’s innocent of any wrongdoing – a hapless victim of circumstance, surrounded by deaths she neither caused nor contributed to. It’s up to the reader to decide whether to believe this self-portrait or question it, and the resulting ambiguity makes The Cocktail Waitress one of Cain’s most unsettling, unstable books.

Cain worked on The Cocktail Waitress pretty much up until his death. He never published it, though he did show drafts to his agent and his publisher. He wasn’t satisfied and kept tinkering; even his typed manuscripts contain corrections and changes in his nearly illegible handwriting. The book’s ending in particular bothered him, and after writing multiple versions he warned his publisher it might change again: as quoted in the biography Cain, he wrote to them, “If you’re dealing with me you may as well get used to it. I work on an ending ceaselessly.”

But no one works on anything ceaselessly. With Cain’s death, the unpublished manuscripts of The Cocktail Waitress disappeared among his voluminous papers like the crate into the warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

How did it get rediscovered? Well, there were passing references to the book’s existence here and there – in interviews Cain gave toward the end of his life, in which he mentioned he was working on it; in the biography, where its premise is briefly summarized; in some of Cain’s records and correspondence. In April 2002, back when Hard Case Crime was just a glimmer in the eyes of two writers with a crazy notion that old-fashioned pulp crime fiction needed to be revived, I began corresponding with Max Allan Collins, the award-winning author who has gone on to be one of our most prolific contributors. In addition to agreeing to write some books of his own for our line, he had suggestions for other authors, living and dead, we might consider publishing. Cain was a favorite of his, and as it happened, a favorite of mine, too. Since picking up a creased copy of Double Indemnity on a used book table while a freshman at Columbia, I’d hunted down copies of every book Cain had ever written and read them all – even the obscure ones, even the weaker ones, even the ones no one had read in decades. But Max had heard about one I never had: The Cocktail Waitress.

I spent the next nine years tracking down the book and securing the right to publish it.

The first problem was locating the manuscript. As it turns out, certain drafts – some partial, some complete – were housed in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, where nearly one hundred boxes hold papers from all stages of Cain’s life. But I didn’t know that then (this was before the Internet made finding everything in the world so simple), and I spent the first couple of years canvassing friends and contacts in the publishing field, book collectors, academics, anyone I could think of who might have a lead. But no one did. Finally, when I learned that my Hollywood agent, Joel Gotler, had inherited the practice of an old-time agent named H.N. Swanson – “Swannie,” to his friends, colleagues and clients, one of whom was none other than James Mallahan Cain – I asked Joel if he might be willing to look through Swannie’s old files and see if anything turned up. Joel looked – and a few days later I got an envelope in the mail containing the manuscript of The Cocktail Waitress.

Talking to the New York Times later, I described the moment of opening that envelope as feeling like a scene out of a Spielberg picture – to stick with Raiders as our touchstone, like opening a tomb sealed for centuries and seeing the Lost Ark peeking out at me. But this moment turned out to be just the start of the quest, not the end. Because it became apparent quickly that there was more than one Cocktail Waitress to be found.

Sometimes a writer dies with his current work in progress unfinished. But the situation with The Cocktail Waitress was different. We not only had a complete and finished manuscript, we had several, as well as several partial manuscripts and fragments, some consisting of no more than a few lines on a single sheet of notepaper, others going for a dozen pages or a few dozen.

None of the manuscripts were dated, making establishing their order difficult (though one – the third-person draft of 107 pages – was labeled “O R I G I N A L”). Many contained the same scenes, only arranged in a different order; some had the same scenes only written slightly differently, with the differences sometimes being purely stylistic and sometimes being of great import to the book.

For example: After her first conversation with Mr. White, in one draft the scene ends with Joan thinking, “I knew I’d made a strike that could be important to me, but what stuck in my mind was: I wished I liked him better”; in another, Cain penciled through “I wish I liked him better” and wrote in, “Pale or not, he was very goodlooking and I liked him.” Quite a difference!

When I finished editing the book and read it over from end to end, I was reminded of why I fell in love with Cain’s writing in the first place. When I was 18 and cracked the slim spine of that first Cain volume I’d found, he stirred something inside me – enough so that I felt compelled to track down and read every word the man ever wrote. That voice, reaching out to me across half a century, grabbed me by the lapels, or perhaps by the throat, and it hasn’t let go yet.

The Cocktail Waitress (Titan Books) RRP £16.99 is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks