The story goes on, Anon

An anonymous imagining of Barack Obama's 2012 re-election campaign is the latest attempt by an author to disguise their identity. It's been going on since Beowulf, says Arifa Akbar

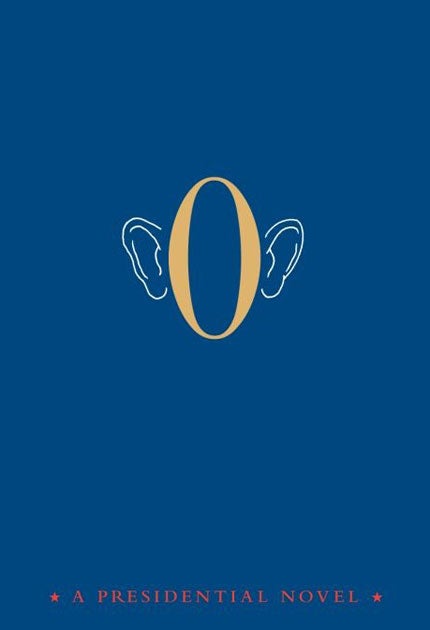

The great guessing game over the mysterious author of O: A Presidential Novel came to an end when Time magazine pointed its finger at a former Republican aide, Mark Salter, who – while not owning up to the deed – did not deny the claim or threaten to call his lawyers either.

Salter's apparent outing was seen as a triumph for the tenacious truth-chasers of Washington who refused to let up until they had discovered the true penmanship behind the thinly fictionalised imagining of Barack Obama's 2012 re-election campaign. But even a brief study of anonymity in art and the cat-and-mouse game it sparks, suggests that this outcome – a dramatic discovery after a media firestorm of speculation and publicity – was what this "reluctant" author was really hoping for.

Anonymity is arguably a powerful modern-day marketing tool. We only need think back to the foxhunt that followed the anonymous publication of Primary Colors in 1996 (a roman à clef of Bill Clinton's presidential campaign to which the journalist Joe Klein owned up).

Or there is the international intrigue and rocketing market value of graffiti art by Banksy, currently adorning various walls in downtown LA. What about the excitement that swirled around the masked members of the 1990s House music ensemble, Daft Punk? Or even the multiple book deal success of the erotic blogger, Belle de Jour, who was later revealed to be the science researcher Dr Brooke Magnanti. The high-profile anonymity in literature today is a far cry from the concept of the unauthored texts of medieval times.

Of course, while some ancient and medieval texts are anonymous due to lost documentation, such as in the case of Beowulf, the majority of medieval scholars and writers viewed authorship as unimportant, partly because of a cultural emphasis on re-telling and embellished classical stories rather than inventing new ones.

This was not the case in the history of art, according to Caroline Campbell, who is a curator at the Courtauld Gallery. It was certainly not the case during the Renaissance, when artists commanded celebrity status and even those who produced risqué works chose to give authorship to their illicit creations.

"The idea of anonymity we have today we do not find in the early period. The artist, Marco Antonio Raimondi, for example, created a salacious series of prints called I Modi (Making Love), which were banned on the Papal register. They were circulated and people knew who had done them. He may have risked getting in trouble for them but there was no conscious hiding of his identity," she says.

It was only in the latter half of the 20th century that the anonymous medium of graffiti art emerged in the urban centres of New York and London as a potent subculture.

Yet in an ironic, modern-day twist, even this art-form is now authored, having entered mainstream culture. Graffiti artists have recognisable identities ("tags") and galleries – including Tate Modern – have begun staging graffiti art exhibitions.

The ideal concept of anonymity in art originally signified the "egoless artist" who was happy to see his or her identity subsumed by the work they produced.

Later, it became associated with the "radical artist" who produced work too transgressive or incendiary for authorship. Yet now these definitions might appear naive. Some suggest the true impulse behind anonymity is an egotistical one that relies on being found out.

The success of an unnamed artwork is predicated on "high profile anonymity", in which the mystery of authorship drives its fame, lending the work of art a highly marketable, charismatic edge.

This model inverts the original concept of anonymity as a surrender of the ego and assumes a false modesty.

John Mullan, an academic and author of the book, Anonymity: A Secret History of English Literature, suggests this paradox of "starry anonymity" dates back hundreds of years. The outing of an anonymous artist was, and is, inspired by our collective desires to uncover an unknown identity and a secret burning desire in the artist to be discovered.

Just as in 19th century Britain – when there was a frenzied nationwide search for the author of Jane Eyre after Currer Bell was discovered as being pseudonymous – so the author of O: A Presidential Novel hoped the same thing would happen, believes Professor Mullan.

"It's a marketing trick which the marketers think is new, but they are rediscovering something that was used much more elaborately and subtly in the 19th century," he says. The author of O was "desperately hoping" to be discovered, says Professor Mullan and not – as his publisher at Simon and Schuster claimed – be left in the shadows.

Historically, there have been valid reasons for artists choosing not to be named. Many have written anonymously to avoid prosecution, moral approbation and shame.

Erotic literature had a heavily anonymised authorship, enabling writers to publish without charges of moral corruption. The most infamous – and popular – publications include the 1901 novel, The Autobiography of a Flea and The Story of O, a novel about dominance and submission written in 1954 by Anne Desclos under a pen-name.

Anonymity was assumed for incendiary or controversial works, too; The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man was published in 1917 and gave a frank account of being mixed-race at a time when this would have shocked the public. A Woman in Berlin, similarly, was an anonymous diary describing the experiences of a German woman as her country is defeated in 1945.

In both these cases, the revelation of identity could well have left them in danger. There are some similar modern day instances of this; in the case of Night Jack, a blog written by an unnamed police officer (later revealed to be Richard Horton) which was awarded the Orwell Prize for its gritty eloquence, Horton lost a legal battle to keep his anonymity protected. As a serving officer who used his daily jottings and professional experiences as raw material for a blog, he is one example of a writer who appears genuinely not to have wanted exposure. Yet there are relatively few instances of these truly dangerous cases, argues Professor Mullan.

For the most part, anonymity is not forced upon a writer, but it is rather assumed for advantageous purposes.

And the idea of "necessary anonymity" remains unclear in our contemporary age, when there is no fear of being hung or beheaded (at least in the Western world) for sedition, blasphemy, or pornographic works of art.

So what authentic value, beyond the marketing trick, does anonymity offer? Can it provide greater creative freedom and produce truly radical works of art?

Music critics have argued that the electronic music scene of the 1980s and 1990s achieved just this. Groups such as Daft Punk and Art of Noise wore masks and cultivated a nebulous identity and contemporary act such as the American hip-hop artist, Daniel Dumile, who is masked and has multiple identities (the most popular of which is MF Doom) is seen as a direct descendant.

Paul Morley, music writer and co-founder of the 1980s avant-garde synth pop group Art of Noise, argues that the impulses behind his groundbreaking electronic ensemble were both aesthetically radically and attention-seeking – they wanted to do something different but also saw the masks as a way of attracting an audience.

The mystery around their identities unravelled "because of a craving from inside the group to be known and from outside the group to know, even if this was disappointing".

"I think with Art of Noise, the masking and anonymity was first a conscious attempt to blank out, so that the group seemed fluid, sourceless and flexible. They could be from anywhere and therefore do and be anything; not tied to genre or place. The group could theoretically always change their character and personality and, to some extent, the music and the sounds became the image; became the work. It was definitely done to make something that was more entertaining and enigmatic... It was a way of breaking free of the standard boring idea of the pop group.

"And because it was a collaboration between backroom studio operators, usually faceless, then it became a way of creating a group from mechanics, technicians, engineers... The music could be remixed, remodelled, recontextualised. Theoretically, so too could the musicians and the images and names they chose for themselves... Daft Punk's maskedness was also about achieving a sort of unique fluid glamour that broke free of the usual pop presence."

In an age when the cult of celebrity reigns supreme, perhaps it is the case, as Morley suggests, that the act of hiding ones identity, even for playful or attention-seeking purposes, is a radical statement in itself.

A figure such as Banksy who still resists the straightforward celebrity of his fame could be seen to be staging a protest against the modern day cult of personality. Yet curiously, his anonymity has become such a powerful brand that after the British press claimed to have discovered his true identity in 2008 with reports that he was, in fact, a former public schoolboy called Robin Gunningham, this did little to diminish the mystery around him, even after he had ostensibly been outed.

Modern-day anonymity might be good for marketing, says Morley, but this need not undercut its radicalism.

Gorillaz, the "virtual band" of cartoon characters that was founded anonymously by Damon Albarn and Jamie Hewlett, was both avant garde in its intentions and highly marketable.

"I loved Gorillaz, especially when they were more intangible and murky, because in a world of relentless self-serving publicity, it is refreshing to have this kind of withdrawal; this other way of drawing attention," Morley says.

"In the end, with Gorillaz, the vagueness was a powerfully tantalising marketing force and the soundtrack to the vagueness seemed more vivid and attractive because of the relative anonymity."

"O: A Presidential Novel" is published by Simon & Schuster

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks