Why I spent three years tracking down the original serialisation of Tom Wolfe's The Bonfire of the Vanities

The first version of this classic novel was published in instalments in Rolling Stone – but tracking it down proved an all-consuming quest

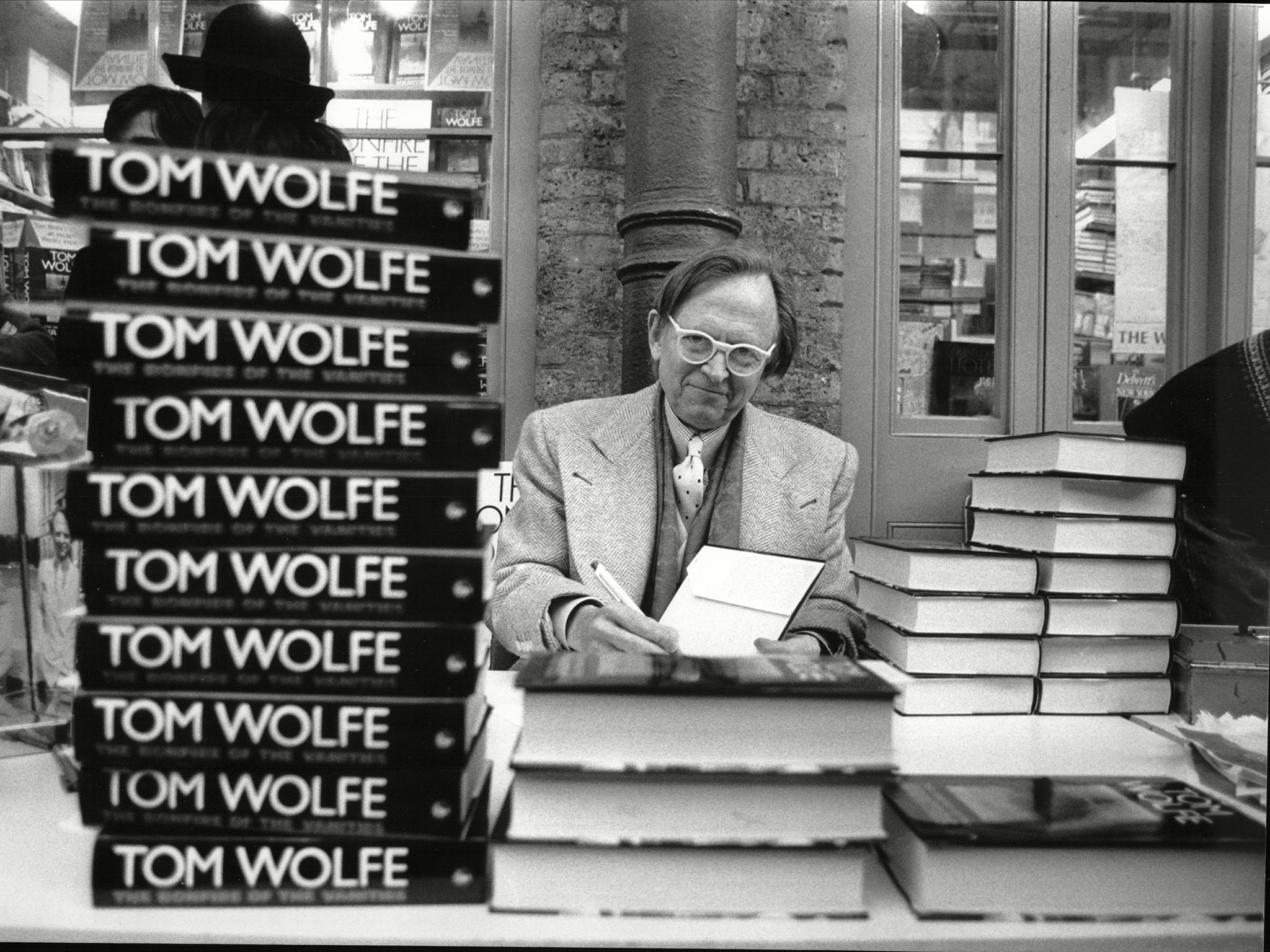

In the outpouring of tributes following Tom Wolfe’s death, his 1987 novel The Bonfire of the Vanities proved to be his most celebrated and widely admired work. What barely garnered a mention was that this vital piece of literature was actually a remake of a 27-part serialisation, published in Rolling Stone magazine a few years previously.

It’s hard to imagine many people noticed, or cared, about this omission – but I did. I spent three years tracking down this early version and, in an age when we expect all media to be digitised and available at the click of a button, it proved more difficult than I could ever have imagined.

There have been acres of print devoted to The Bonfire Of The Vanities in the three decades since it was published. Often described as the defining novel of the 1980s, it was a scathing portrayal of the haves and the have-nots of New York City, weaving together Wall Street, the media and the legal system.

After acclaimed works of non-fiction such as The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and The Right Stuff, Wolfe began researching his first work of fiction in 1980, spending four years tinkering with it before Jann Wenner, owner of Rolling Stone magazine, offered him $200,000 to serialise it on a fortnightly basis.

A fan of Dickens and Thackeray, both of whom had important works serialised in magazines a century earlier, Wolfe agreed, hoping it could help tackle his procrastination, plus provide much-needed income.

The critical reaction wasn’t great. In the Times Literary Supplement, Christopher Hitchens sniffily dismissed it, saying: “When pudding came to proof, the only Dickensian thing about this capacious entertainment was its serialisation, episode by episode, in a monthly magazine.” Only a cynic would suggest this had something to do with the speculation that Peter Fallow, the alcoholic journalist, was modelled on Hitchens.

Wolfe was downhearted at the response, however, later saying: “I had the distinct impression the population was not thronging the docks waiting for the next issue, the way they did with Dickens.”

After the final chapter was published in August 1985, Wolfe spent the next two years on an extensive rewrite, altering key plot points and characters until it became the multimillion-selling novel we know today.

I was late to the party, only stumbling across the book a decade ago in my mid-twenties. But I was instantly struck by Wolfe’s style – caustic but elegant, and always brutally funny. This was exactly the writer I’d been looking for.

I devoured everything else he’d written, starting with his other major works, then tearing through collections such as The Purple Decades, until I found myself ordering obscure old copies of his illustrations and collected interviews.

But one book proved frustratingly elusive: the early serialisation of The Bonfire Of The Vanities was nowhere to be found. I’d assumed it would have been rereleased following the success of the 1987 novel, or at the very least that some other Wolfe devotee would have scanned and put it online.

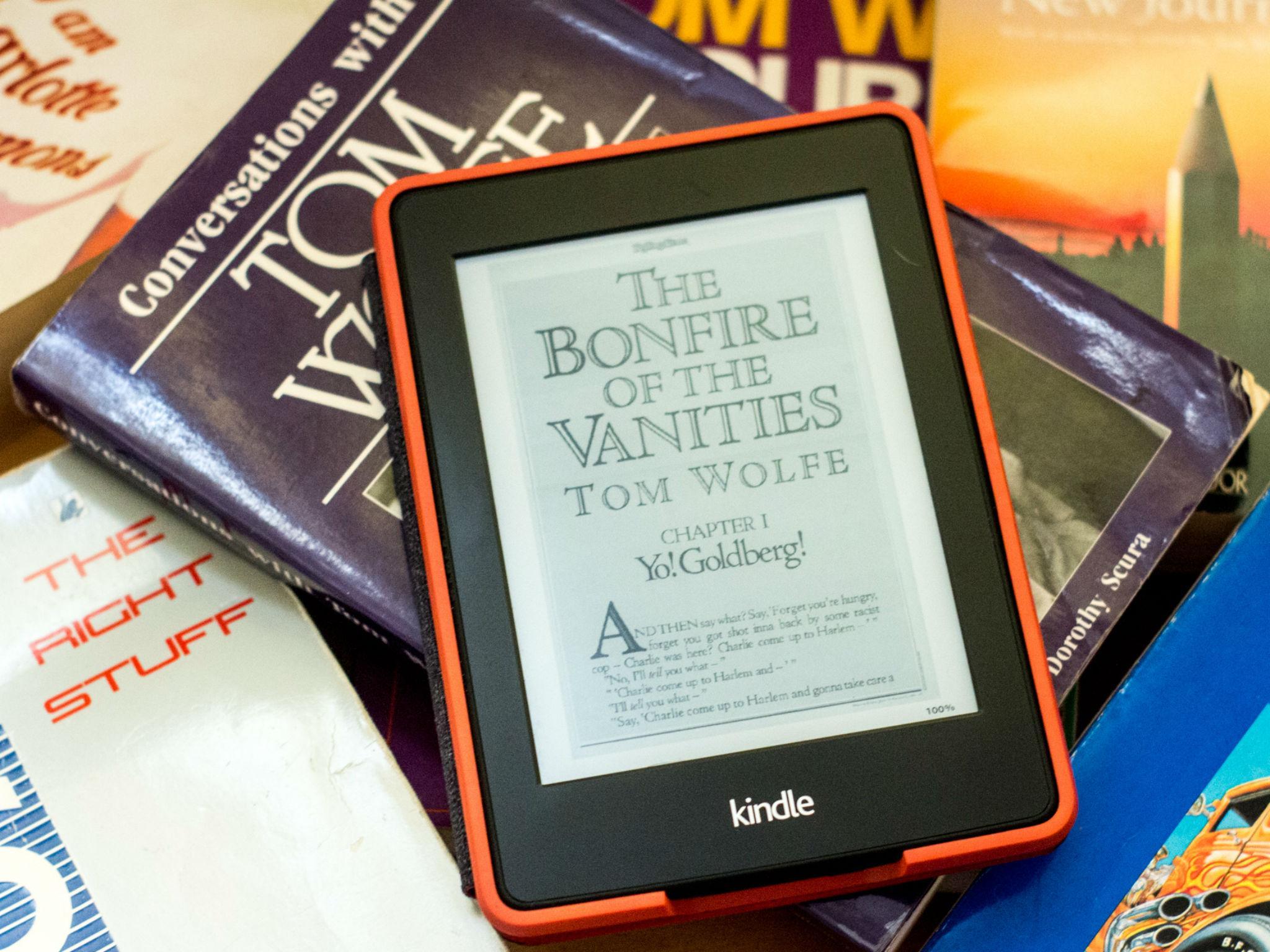

I found nothing. It rankled that over six million ebooks are available on the Kindle store but the prototype of one of the most important books of the 20th century had been practically erased from history.

It felt all the more ironic given the book’s title. The first vanities bonfire happened in Florence, Italy in 1497 when supporters of friar Girolamo Savonarola publicly burned what they considered vain objects – books, art, music, anything deemed immoral. It’s easy to see Wolfe playing the part of Savonarola, eradicating all evidence of his early attempts at fiction.

In a 1988 interview, Wolfe said: “One of the great things about journalism is, it’s thrown away.” And this was always intended to be a transient work.

But I have a habit of getting obsessed with the lesser-known works of people I admire, or in DJ terms, “cratedigging”. Whether it’s comedy (I maintain the Mrs Merton audio cassette is UK comedy’s finest moment), TV (I probably have more videos of Danny Baker’s TV appearances than he remembers making), or music (my specialist subject on Mastermind would be obscure European disco), there’s no greater thrill than finding some long-forgotten work of art and appreciating it as much as the creator’s other, more high-profile, output.

I became convinced the Rolling Stone serialisation was another of these gems. It played on my mind endlessly. In early 2015, I finally decided to track it down, whatever the cost.

At first, it seemed simple. Rolling Stone magazine had recently teamed up with Google’s Newsstand app, declaring that its entire back catalogue was now open to the public. But this proved not to be the case – the versions available had just a handful of recent stories and no way to access the archives.

Then I found a website that promised “40 Years Of Rolling Stone Online – Every Issue, Every Page”. Unfortunately it was last updated in 2009, and despite its claims, had no way of accessing any back issues.

I gave up on digital media and decided to source physical copies. I eventually found an America-based back issues site which had all 24 issues. It’d cost over £500 to buy the lot. Expensive, sure, but a small price for what I’d become convinced was the holy grail of literature.

Then a breakthrough. By chance I discovered the Rolling Stone archives had been released on CD-rom, back in 2007. I eagerly handed over the £40 price tag for a used copy – I was saving £460!

True to form, the discs didn’t work. They used an obsolete viewing format that immediately crashed any modern PC. Undeterred, I dug out an ancient laptop and finally saw the first pages of the book I’d spent the past year tracking down.

I wasn’t willing to read it on a rickety old laptop, so the next step was extracting the images to collect together as an ebook. Around this time, I was engaged to be married, with the big day looming. While my wife-to-be was organising lavender centrepieces, I was hunkered down in the box room, working out how to extract DJVU files into PRN files so I could convert them into JPEGs.

Somehow, she still married me.

This process took months, but I came across a reader’s letter in the September 1984 issue that convinced me it was all worthwhile. Doug Robinson of Colorado proclaimed: “The worst thing about Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire Of The Vanities was that there were only a couple of chapters. I’ll be waiting for the next instalment. It’s definitely the Great Stuff.” This was the confirmation I’d been waiting for – forget Hitchens, I put my faith in Doug.

I wanted to share this thing I’d found with the world. I wrote a number of letters to Tom Wolfe, via his fan mail address, asking could I share my cobbled-together version online? My letters were returned unopened.

I contacted his publishers and agents, past and present, and even mailed Jann Wenner, head of Rolling Stone magazine. My requests were ignored.

When a friend told me he was going to New York for a holiday, I asked if he’d hand-deliver my letter to Tom’s house. His concerned response made me realise I was probably taking this too far.

Regardless, I had the book, collected together in an enormous PDF file, just in time for the 30th anniversary of the 1987 novel. I was, and probably still am, one of a handful of people to have read this early Wolfe in the 21st century.

Was it worth it? Well, it wasn’t exactly the lost classic I was hoping for.

What is striking, however, is just how much changed – practically every sentence was reworked, entire characters were cut out or changed career, usually for the better.

The plot – never Wolfe’s strongest suit – is undeniably shambolic, with countless dead ends and loose threads. But there are noteworthy delights for the Wolfe-obsessive buried within – in the final chapter, after Sherman McCoy’s trial, his apartment was sold to a “thirty-seven-year-old bond trader, for $2.2 million”. He may have been a writer in 1984, but a bond trader is exactly what Sherman became in the revised version.

But ultimately, as Wolfe no doubt knew, it’s merely an example of a great nonfiction writer learning how to write fiction – and fumbling through it all in a very public manner. It’s understandable that he had no interest in resurrecting this formative work.

This is far from the only example of lost literature. Many other important works have fallen off the map, from Lewis Carroll’s missing diaries to Stephen King’s epilogue to The Shining, both of which exist – or previously existed – but not in any public forum.

And perhaps that’s how it should be: sometimes these things are best left alone. Unless you’re an obsessive geek, in which case, drop me a line, let’s chat. My laptop’s at your service.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks