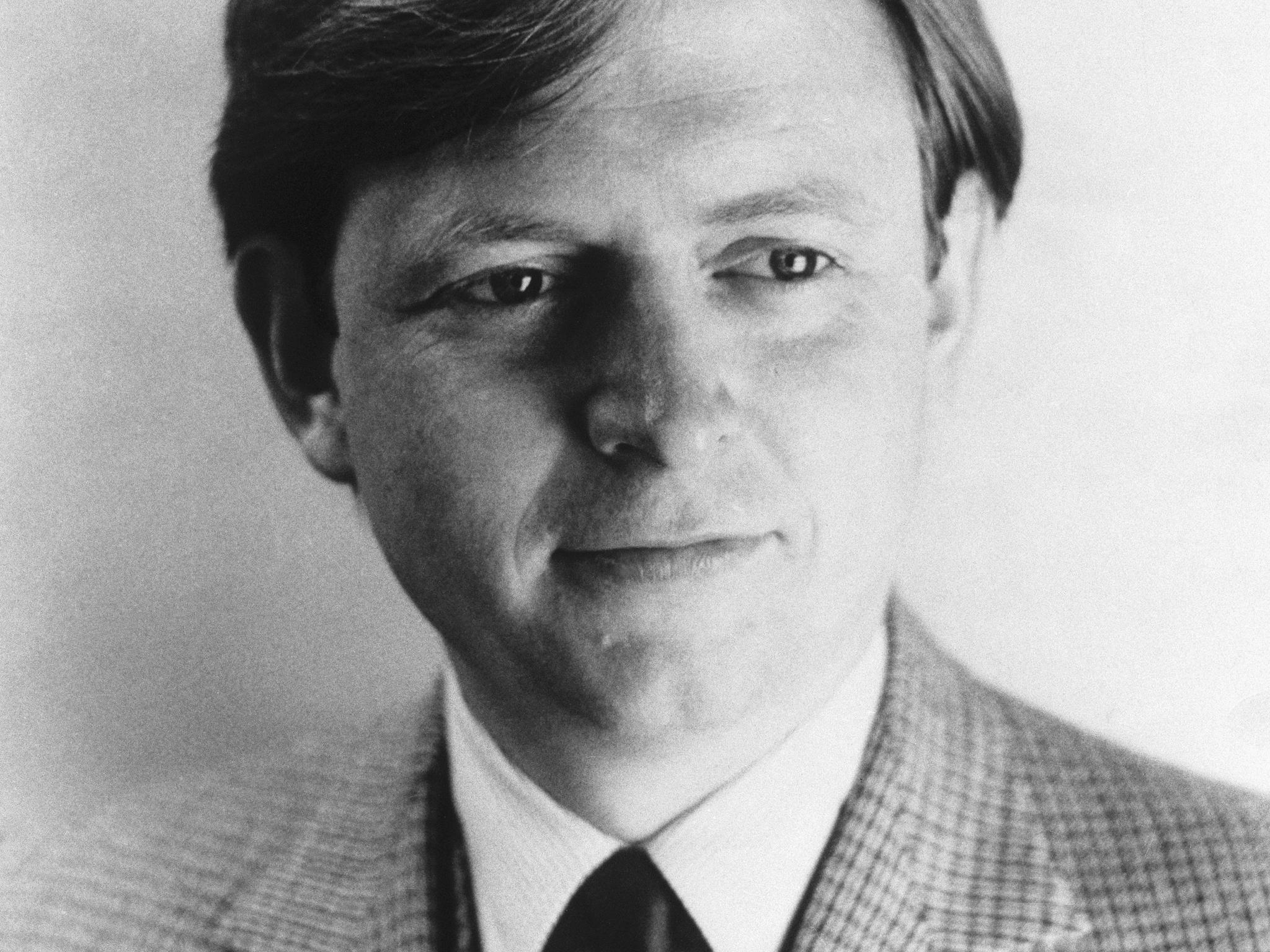

Tom Wolfe: The writer who dissected and deconstructed America's absurdities

A writer who blurred the distinction between reportage and fiction

Effortlessly, elegantly, Tom Wolfe bestrode both fiction and nonfiction. He was an acute observer of the evolution of American culture over the second half of the 20th century, a roaming anthropologist who surveyed the new tribes of East Coast and West Coast and everywhere in between. His most exemplary work remains The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968) which, as well as providing an object lesson in the literary experimentation of “New Journalism”, takes the writer and the reader on a madcap, LSD fuelled bus journey across America with the Merry Pranksters, in a style at once objective, subjective, and hallucinatory.

Wolfe’s first collection of essays, originally written for Esquire and the New York Herald Tribune, was The Kandy-Colored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (1965) in which the author turns on and tunes in to the subcultural obsessions of custom cars, Las Vegas, pop music, and stock car racing (an essay that was turned into the film, The Last American Hero).

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test became a manual of the hippy movement. But just as he was capable of writing seductively about surfing (notably in The Pump House Gang, focused on a group of surfers in La Jolla) without ever getting wet, Wolfe himself was never a hippy. He was too disciplined and controlled for that. He didn’t sample the drugs he wrote about. His signature sartorial style consisted of a three-piece white (or cream) suit, with minor variations. While sympathising with the aims and ideas of his messianic hero Ken Kesey, Merry Prankster-in-chief and author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – which in effect denounced conservative, institutional America and was a hymn to liberation – Wolfe himself remained discreet, almost invisible in his own writing. In his self-effacing manner he was less like, among his contemporaries, Norman Mailer or Hunter S Thompson, and more of a modern-day Flaubert, even if Flaubert would probably not have used words like “POW” and “boing” quite so often – or punctuated his prose with quite so many exclamations marks.

Some critics of Wolfe’s style maintained that he blurred the distinction between reportage and fiction. It is true that his attention to idiom and idiosyncrasy and his formal inventiveness inevitably led him in the direction of the novel.

The Bonfire of the Vanities may have been the quintessential novel of the 1980s. Modelled on William Makepeace Thackeray’s 19th-century Vanity Fair (which provided the original title of the book), set in a New York that is both highly particular and an allegory of the nation as a whole, it takes a narcissistic vision of Wall Street, exemplified in the ironic phrase “Masters of the Universe”, and the everyday racism that divides Manhattan and the Bronx, and brings them into collision with the legal justice system and the media (represented by an alcoholic expat Brit).

Wolfe’s second novel, A Man in Full (1998) replaces bond trading with real estate and transposes the clash of libido and lucre to Atlanta, Georgia. It was another bestseller, even if slated by John Updike as mere “entertainment” and described by Norman Mailer as “a 742-page book that reads as if it is fifteen hundred pages long”. I Am Charlotte Simmons (2004) depicts how it all goes wrong for a talented young student of neuroscience from a poor background attending an elite university, preoccupied mainly with sex and sport. It also won that year’s “Bad Sex in Fiction” award.

Wolfe lampooned left-wing intellectuals in Radical Chic and apotheosised astronauts in The Right Stuff. He coined the phrase, the “Me Decade”, originally about the 1970s. His most recent publication was The Kingdom of Speech (2016) a freewheeling theory of the evolution of language, critical of Darwin and Chomsky.

Stylistically, Wolfe was notable for ellipsis, over-punctuation, but above all onomatopoeia. His technique was sometimes referred to as “psychedelic” (among other less flattering adjectives). But the reality was that he really listened to the way that people spoke and had a shot at capturing the oral on the page, including nonce-words such as Unnnnggggghhhheeeee and Ggghhzzzzzzzhhhhhhhggggggzzzzzzzeeeeeong and arrrrrgh.

Wolfe invoked Emile Zola’s downbeat depictions of Paris and coal mines at the end of the 19th century as his model, but perhaps the 20th-century’s Jean-Paul Sartre provides a more fitting slogan for his melancholy aesthetic: “everything is doomed to failure”. Sherman McCoy, protagonist of The Bonfire of the Vanities, deserves to be seen as a tragic figure. In all Wolfe’s works, the pleasure principle smashes up against the reality principle with spectacular and dismal results.

Wolfe alternately mythifies and de-mythifies. He falls in with and even temporarily surrenders to American utopias – take, for example, the Playboy mansion of Hugh Hefner – only to dissect and deconstruct their absurdities.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks