Wilko Johnson interview: Dr Feelgood guitarist on the day he was diagnosed with cancer: ‘I was alive!’

The rock legend discusses life after his misdiagnoses and his new book Don’t You Leave Me Here

In a year in which so many famous faces have appeared in the obituary columns, one is notable by its absence: Wilko Johnson’s. Diagnosed with inoperable pancreatic cancer in 2013, he was given just 10 months to live. But three years on, now aged 68 and well into this most unexpected autumn of his life, Johnson is cured and very much alive. Not quite in rude health, perhaps – the operation that saved him removed a three-kilogram tumour, and he won’t be seeing his spleen, much of his intestines, or his pancreas again – and he takes 20 pills a day to help keep him stable, but nevertheless alive.

“I still remember the morning the doctors told me I was cancer-free,” he says. “Snatched from the jaws of death! I mean, wow, what a feeling.”

But that was then, and the “wow” factor has diminished considerably ever since. The depression that had dogged him for most of his adult life, a condition that vanished completely during what he thought were his final months, has returned with a vengeance.

“Oh, I’ve always been prone to it, it’s just a regular cycle I go through. I see sunny days now and feel awful, moping about, when I know I should be grateful just to be here. Who knows, maybe it’s better to be dying?” He coughs up a laugh that sounds like a power station burping. “I don’t know, I just don’t know.”

It’s two o’clock on a blazing May day in London, and Johnson, flanked by his book PR and his son Simon, arrives at his publisher’s office under an existential thundercloud of his own devising. He looks inconsolable. Our handshake sets his square jaw rigid, and he avoids all eye contact. When we settle in a boardroom upstairs, he is asked if he fancies anything to drink. “Coffee,” he says, reaching for its modern moniker. “‘Latte’? Is that what they call it?”

This week his memoir, Don’t You Leave Me Here was released. He has been the subject before of authorised biographies – the most recent in 2014 – but this is the first time he has put pen to paper himself. Much of it was written, he confesses, in an anxious stupor at three o’clock in the morning.

“I thought they just wanted the cancer stuff,” he says of his publishers’ requirements, “but turns out they wanted everything else as well.”

So he trawled through his Dr Feelgood years, the Canvey Island pre-punk act for which he played guitar, and whose appealingly roughhewn pub rock brought them unlikely success in the mid-1970s. These recollections required him to revisit the furious feuds he would have with the rest of the band, most pertinently frontman Lee Brilleaux, and which would prove their ultimate undoing.

“Lemmy [late Motorhead singer] said to me that speed freaks and drunks could never get on together,” he says. Johnson was once an example of the former, Brilleaux – who died of cancer in 1994 – the latter. “I’m not sure you can really dismiss it as easily as that, but who knows? Maybe.”

He says that the hardest part of the book to write were the passages that concerned his wife Irene, who died of cancer in 2004. “I loved her. I still love her. We were together 40 years. I think about her every day.” He stares off into the distance, bulbous eyes straining to be released from their sockets. “I couldn’t write about that without breaking down. I just got so very upset.”

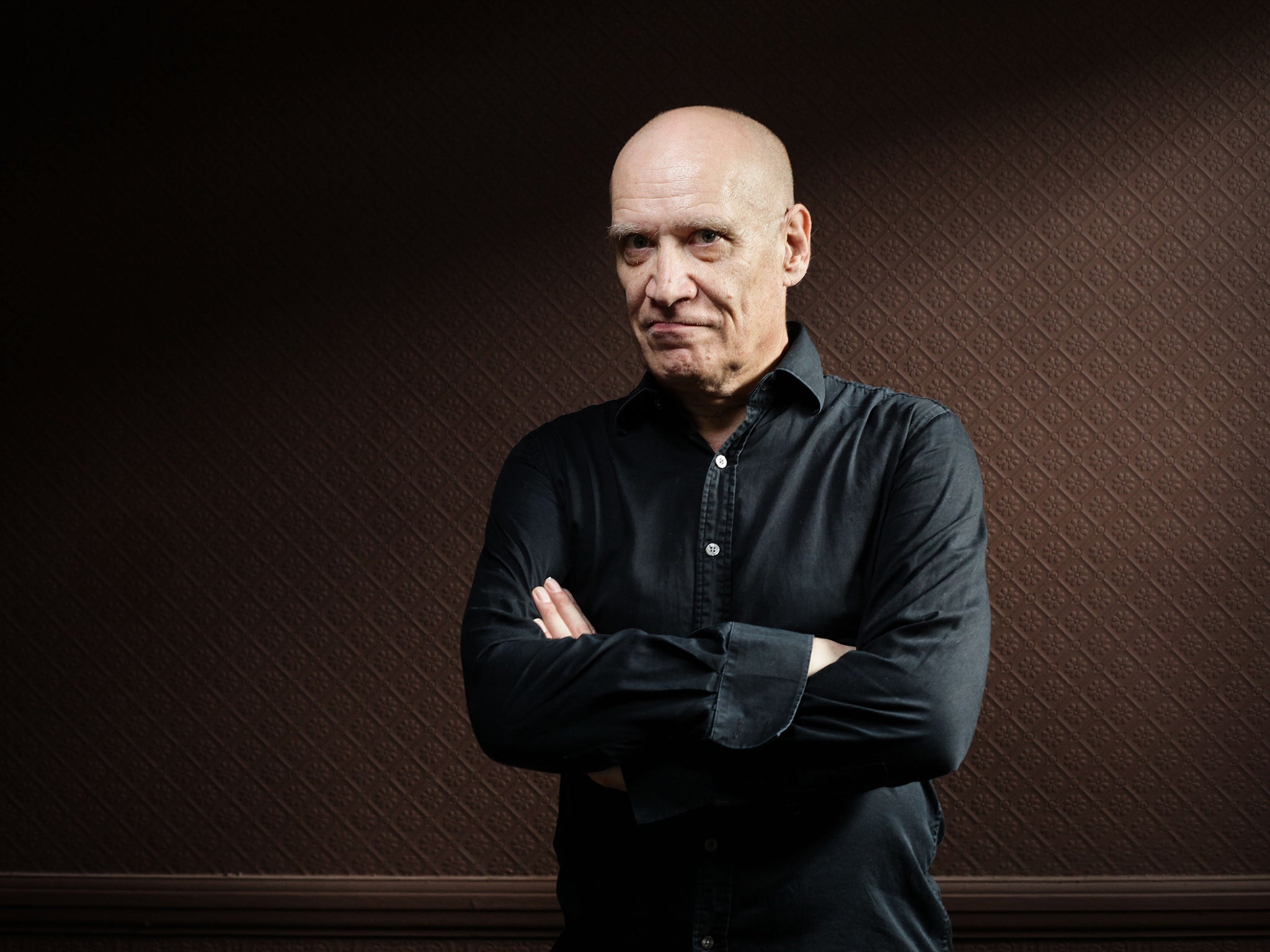

Johnson’s fabled physiognomy is quite something to behold up close. He looks fantastic, a caricature of malevolence, all bulging eyes and bald head, the perma-frown corrugating his forehead and giving him the look of someone on the brink of losing their patience so combustibly they might never find it again. He resembled the Grim Reaper long before he fought the Grim Reaper and won. Dressed as he always is, head to toe in black, his smile is an ominous grimace, and his open palms resemble shovels. He curls one around his latte now, brings it to his lips and frowns. “Always preferred Nescafe, myself.”

Dr Feelgood broke up, bitterly, in 1977, and ever since Johnson has lurched, as he puts it, “from one chaotic moment to another. But then, you know, the band succeeded far more than I ever thought we could, so success always seemed like a very lucky thing. I never expected it to happen again just because I went solo. I just drifted along, often making terrible misjudgements. But I made a living.”

As Pete Doherty might one day experience should he make it into his 60s, the British public tends to react generously when our nihilistic rock stars fail to die of their foibles. As he entered his seventh decade, Johnson began to enjoy something of a career renaissance. The film director Julien Temple made two documentaries about him – Oil City Confidential, The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson – which led to him being offered the role of a mute executioner in Game of Thrones. And then he began to win awards with the word “Legend” inscribed upon them, thus elevating him from cult hero to national treasure.

But then came the cancer diagnosis.

“Everybody must picture it in their minds, right?” he says. “What it would feel like to have a doctor say: you’ve got 10 months.” Johnson’s own reaction took him by surprise. “I just felt absolutely calm. I did not flutter. I walked outside into a beautiful winter’s day, and felt this rush of elation. I was alive! Alive!”

He fully expected that feeling to fade, but when it didn’t he became unusually productive, embarking upon an emotional farewell tour, and recording a hit album with The Who’s Roger Daltrey. And then something remarkable happened: a doctor at one of his shows became convinced he was not showing symptoms of imminent mortality. He referred him to a cancer specialist, who later pronounced that the cancer was operable after all. Wilko lived.

“When this book of mine was at the lawyers,” he says, “they told me that I had a strong case for suing those doctors for that misdiagnosis. But I let it go. I didn’t see that taking action against an NHS hospital would be useful to anyone. They made a mistake, yes, but that mistake led to one of the most fantastic years of my life.”

Johnson says he can’t quite summon up the sensations of that fantastic year now, and so life has reverted to what it always was: complicated and occasionally chaotic.

“I’ve just got to keep busy,” he says. “That’s the key, I think. But I keep thinking I should have been dead two years ago, and yet here I am. It’s still hard to take in, to be honest with you.”

Don’t You Leave Me Here by Wilko Johnson is published by Little, Brown.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks