Seamus Heaney obituary: Nobel Prize-winning Irish poet

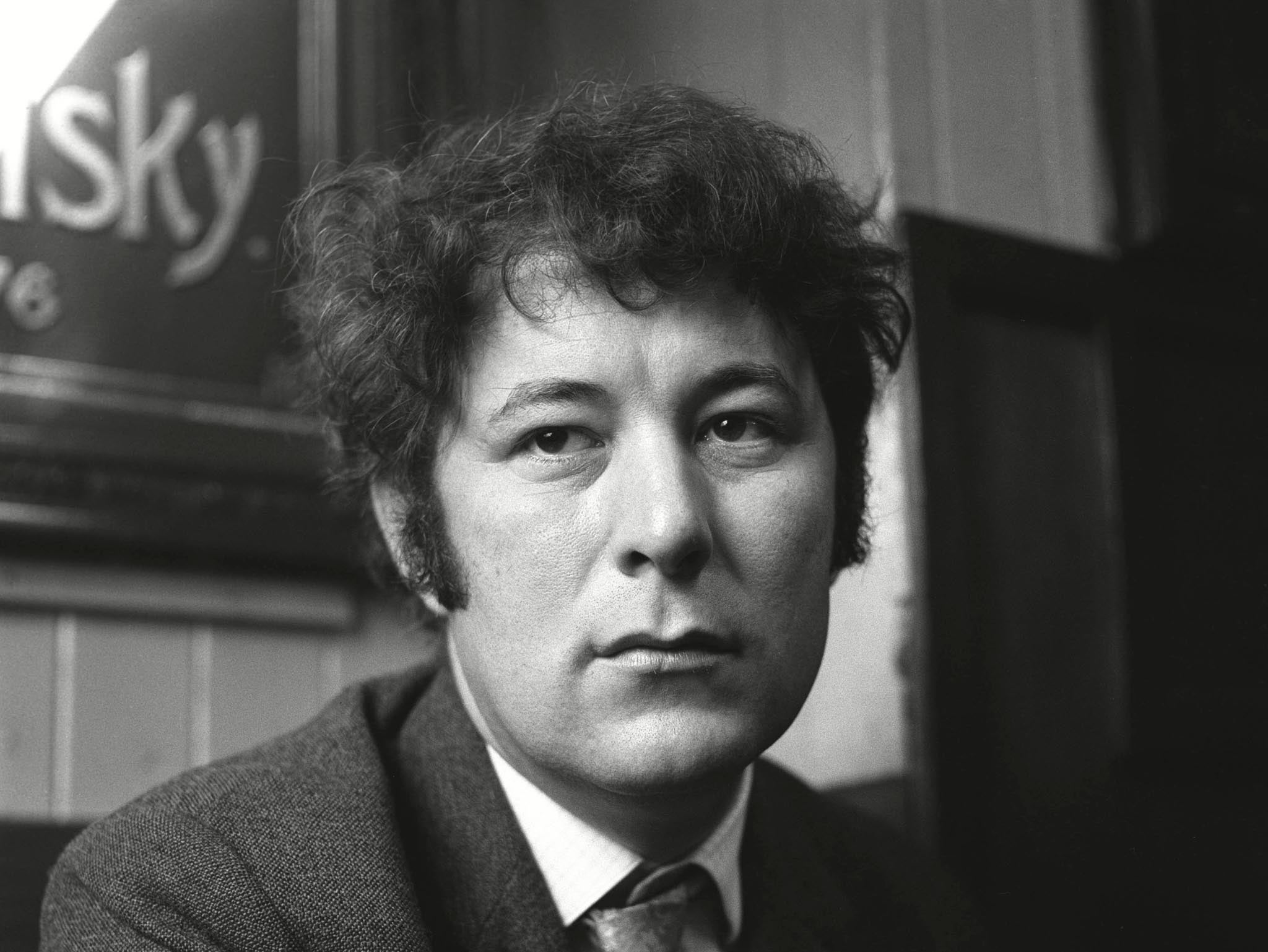

He was described in Punch as writing ‘with the authority of a man who has his own vision of the world’

Seamus Heaney, who has died in hospital in Dublin at the age of 74 after a short illness, was probably the best-known poet in the world. He is irreplaceable, and for his many friends and admirers there will be a tremendous sense of private as well as public bereavement.

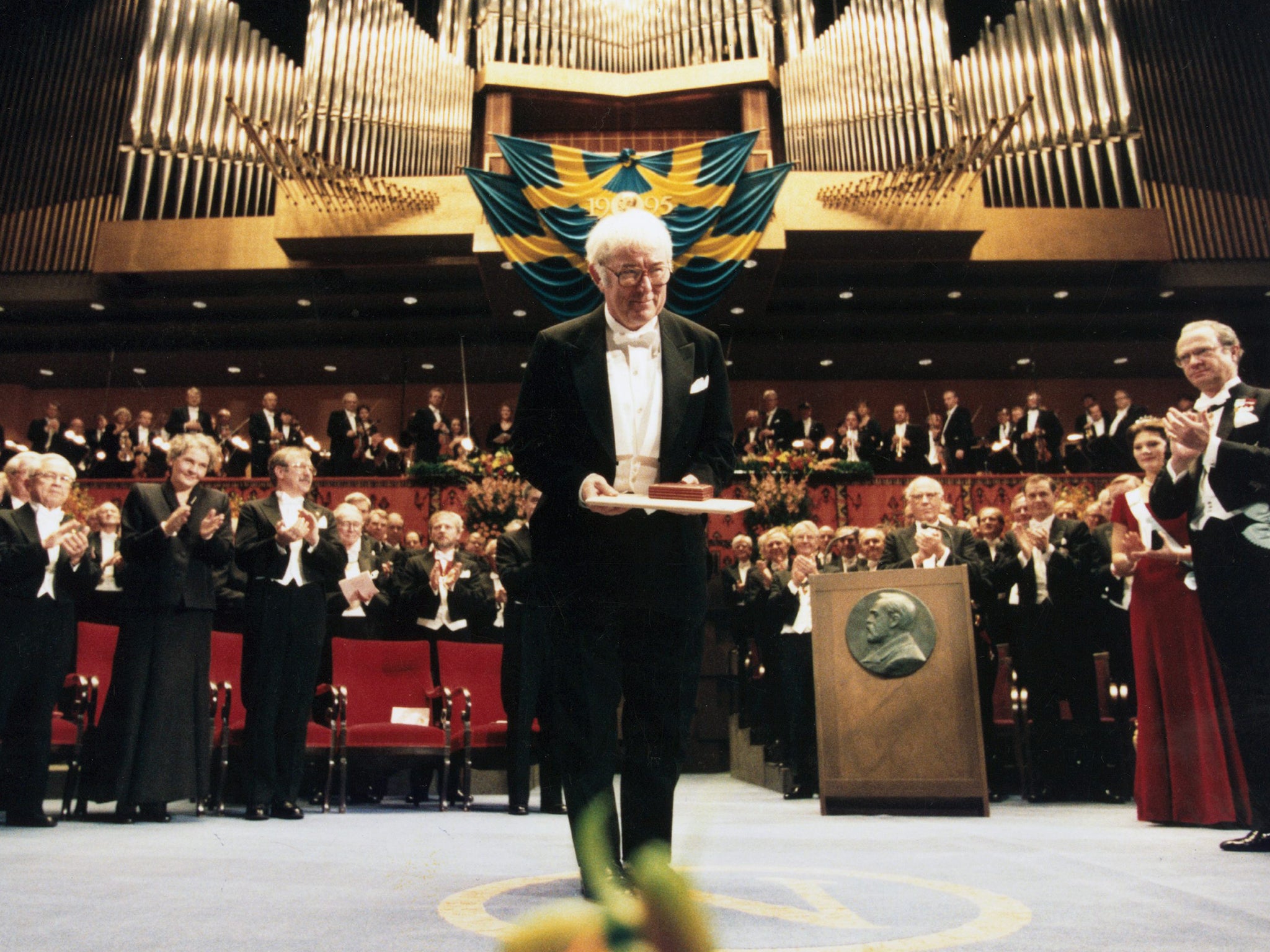

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, delivered in Stockholm in 1995, Heaney recalled his first encounter with European languages via the radio in the kitchen of his wartime Co Derry home. Overhearing fragments of foreign sentences, he said, as the dial was moved from one accustomed station to another, “I had already begun a journey into the wideness of the world. This in turn became a journey into the wideness of language, a journey where each point of arrival – whether in one’s poetry or one’s life – turned out to be a stepping stone rather than a destination, and it is that journey which has brought me now to this honoured spot.”

In the same speech, with his customary felicity, Heaney paid tribute to his great predecessor WB Yeats, with whom he had inevitably been compared as far back as the 1970s, when his astonishing career was just beginning to get into its stride. His fourth collection, North (1975), was a stepping stone on the way to his ultimate status as the “greatest living poet” – the most widely read poet in English, possessor of incomparable gifts and impeccable instincts, and all the other superlatives heaped on him.

North was held by some to denote an artistic breakthrough, embodying as it did a new strength and sophistication following on from the pared-down, rural, evocations and intensities of the earlier collections. In Heaney’s native Northern Ireland, though, its reception was less than adulatory. There were complicated reasons for this: for example, the “famous Seamus” brouhaha, which was starting up around this time, made a contrary assessment inevitable in the poet’s home territory. More seriously, with the Troubles entering a horrific phase, it was felt that certain poems in the collection could be read as an endorsement of Republicanism, with Heaney displaying, at best, as one critic wrote, “a culpable ambiguity in [his] responses to atrocity”. Such reservations were, I think, based on a misreading; Heaney was never an apologist for violence, despite the seeming drift of the much-quoted lines about “conniving” in civilised outrage, while understanding “the exact / and tribal, intimate revenge”. His brief was large enough to accord a right of expression to every variety of belief. And if “the dark matter of the news headlines” got into Heaney’s poetry, as it did at intervals from this time on - though always contained within an oblique and subtle, multi-layered and illuminating, modus operandi – the light he was aiming for, he said, “was the kind that derives from clarity of expression, from plain speaking.”

In any case, the voices of dissent soon died away as Heaney’s place in the canon of contemporary literature became unassailable. The list of his honours is breathtaking, from the Cholmondeley Award for Death of a Naturalist onwards, culminating in the Nobel Laureateship. Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard, Emerson Poet in Residence, also at Harvard, Duff Cooper Memorial Award, American-Irish Foundation Award, Member of Aosdana and the Royal Irish Academy; few available honours, national or international, passed him by.

Nothing about Seamus Heaney’s early life suggested the heights to which he would eventually rise. He was born in April 1939 at Mossbawn, near Castledawson in Co Derry, a remote corner of a remote part of Northern Ireland, symbolically placed, he said, “between the marks of English influence and the lure of the native experience, between the ‘demesne’ and the ‘bog’.” The first of nine children of a farmer and cattle dealer, Patrick Heaney, and his wife Margaret (née McCann), Heaney grew up surrounded by siblings and relations, friends and neighbours (“All of us there”), and immersed in the rituals of rural Catholic life.

I come from scraggy farm and moss,

Old patchworks that the pitch and toss

Of history have left dishevelled ....

It was a happy childhood, and immensely fruitful for his future as a poet; but at 11 he began the journey that would separate him from country concerns and, in a sense, from the rest of his family. From Anahorish Primary School he passed the 11-plus and left on a scholarship to board during term time at St Columb’s College in Derry city. (Other St Columb’s pupils at the time included the future politician John Hume, and Heaney’s friend and fellow poet Seamus Deane.)

From St Columb’s, Heaney went on to Queen’s University, Belfast, and graduated with first class honours in English in 1961. After completing a teacher training course he obtained a post at St Thomas’s Boys’ School, where the novelist and short-story writer Michael McLaverty was headmaster. McLaverty was an early influence – “... to hell with overstating it,” he warned, as recorded in the Heaney poem “Fosterage”. The same time the writers’ workshop in Belfast set up and run by Philip Hobsbaum (then a lecturer at Queen’s) provided further support and encouragement. Other members, or occasional participants in the Hobsbaum Group’s activities included Michael and Edna Longley, Bernard MacLaverty, Joan Newmann, Stewart Parker, James Simmons and others; and beyond the Group a network of literary and artistic friendships was evolving, and Heaney established life-long ties with fellow poets such as Michael Longley, Derek Mahon and John Montague (the irreverent Honest Ulsterman magazine described Heaney, Mahon and Longley as “the tight-arsed trio” due to their preference for a formal, rather than an experimental, approach).

Predecessors such as Patrick Kavanagh in particular, but also Louis MacNeice and John Hewitt, indicated a way forward – no more – for the Heaney oeuvre, while a handful of English poets from Wordsworth to Ted Hughes, contributed something to its development. Other kindred spirits of Heaney’s, around this time and for the future, were the painters Colin Middleton and TP Flanagan, and the great folk singer and “free spirit” David Hammond. After some years in the doldrums, Belfast in the early 1960s was shaping up for something of a cultural efflorescence.

In 1965 Heaney married Marie Devlin from Ardboe, near Toome (one of six clever and beautiful sisters who included the author Polly Devlin), and the couple’s first son was born the following year. That year his first collection, Death of a Naturalist, was published by Faber and Faber; and he was appointed to the staff of Queen’s University as a lecturer in English. Door into the Dark came out in 1969, followed by Wintering Out three years later. By this stage it was clear that something unusual was happening in the field of contemporary poetry: Heaney, according a critic in Punch, “writes with the authority of a man who has his own vision of the world”, while the Guardian wrote that he “has the gift of finding a new and consummate phrase to evoke physical qualities ... the result is superb”; for the Observer “has already left the point at which his contemporaries are now arriving”. A year as visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, helped to broaden his outlook. “Something changed, all right,” he told Dennis O’Driscoll in 2007. “It had to do with the intellectual distinction of the people around us, the nurture that came from new friendships and a vivid environment.”

When the Berkeley year was over, Heaney returned with his family (a second son had been born in 1968) to Northern Ireland and a state of escalating Troubles. Internment had just been introduced; five months later came the Bloody Sunday shootings in Derry and then the Bloody Friday bombings in Belfast. The Heaneys had been contemplating a move for some time, and in 1972, Heaney having resigned his post at Queen’s, they left Belfast for Wicklow, where they rented a cottage at Glanmore from the Synge scholar Ann Saddlemyer – “Belfast was where we grew up,” Heaney said. “In Glanmore we were grown-ups when we arrived.” Around this time, Heaney was consolidating literary friendships with Robert Lowell, Ted Hughes and Joseph Brodsky, among others. He had also, through his teaching at Queen’s, got to know some Irish poets of a slightly younger generation, among them Paul Muldoon, Frank Ormsby, Ciaran Carson, Medbh McGuckian. For these, he was already something of an exemplar.

North was published in 1975, with the famous “bog” poems inspired by PV Glob’s book The Bog People (though the first of these had appeared in the previous collection, Wintering Out). Heaney had returned to teaching, at Carysfort College of Education in Dublin, where he continued until 1981; in the meantime, Field Work (1979) and Preoccupations: Selected Prose 1968-78 (1980) had come out, to great acclaim: “deliberate ... restrained ... authoritative and universal”, Harold Bloom wrote of the former in the TLS. “Wry, spare, compressed, subtle, strange” was the verdict of Richard Ellmann. By now, for part of the year, Heaney was engaged as a visiting lecturer at Harvard, and revelling in the acquaintance of new colleagues such as Helen Vendler (to whom his book The Spirit Level is dedicated) and Elizabeth Bishop.

There were many trips abroad, to the US, to Macedonia, Spain, Mexico, Rotterdam, Scotland, France and Japan, but at this time (the late 1970s) the Heaney family was based in Dublin, at Sandymount, a move undertaken partly to facilitate their children’s schooling (a daughter, Catherine Ann, was born in 1973), though they kept on the Glanmore cottage and eventually bought it from Anne Saddlemyer. For Heaney, Glanmore was, and remained, a place of refuge, a writing retreat, somewhere he could escape from the obligations and disruptions consequent on extreme celebrity. Heaney was incessantly in demand, for book launches, exhibition openings, broadcasts, films, lectures, endorsements of this or that enterprise or publication, and his nature made it difficult for him to refuse whatever was asked of him. The pressure was enormous, and his wife Marie had sometimes to intervene to save him from the effects of his instinctive obligingness. His daily post arrived at the house in sackfuls, and consisted mainly of requests, all of which he was loth to decline. It was a matter of courtesy, of a strong sense of the other person’s feelings. When his friend Karl Miller asked him if he was really as nice as he seemed, Heaney replied wryly that he had been “cursed with a fairly decent set of impulses”.

It was a busy life, requiring tremendous energy and dedication. Whatever public obligations he fulfilled, though – and they were innumerable – Heaney always made time for his family and his many friends, and for his own work (which was, indeed, the cause of the international reputation which made him a prime target for besiegers of all kinds, whose importunings would have stopped him from getting on with it). The books continued to appear: Station Island (1984), which, according to John Carey in the Sunday Times, surpassed “even what one might expect from this magnificently gifted poet”; The Haw Lantern (1987); Seeing Things (1991); The Spirit Level (1996); Electric Light (2001). There were also prose collections, translations, and two anthologies, The Rattle Bag and The School Bag, edited with Ted Hughes.

On top of all this, Heaney was a director of the Field Day Theatre Company (founded by Brian Friel and Stephen Rae), under whose auspices The Cure at Troy, a version of Sophocles' Philoctetes, was premiered in 1990. Then came the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, and the attendant to-do, after which demands on his time and stamina entered an even more exorbitant phase. It didn’t affect his output, though. His translation of Beowulf (1999) won the Whitbread Book of the Year award. As Karl Miller (again) observed: “Seamus Heaney believes in keeping going. He has a poem in which a brother does this [his brother Hugh, in the poem of that title from The Spirit Level], and he has done it himself.” Incredible staying power was a Heaney characteristic.

So too was the power of recovery. All this, the activity overload, took its toll; and in 2006, while staying in a guesthouse in Donegal to attend a friend’s birthday party, Heaney suffered a mild stroke. It was the year his 11th collection, District and Circle, had been published; the poem “Anything Can Happen” an adaptation of one of Horace’s odes and obliquely referring to the Twin Towers attacks, might be read, with hindsight, as anticipating the poet’s illness, which came out of the blue and skewed his perception of the world for a time. He was quickly transferred by ambulance to a hospital in Dublin and spent the next five weeks reading detective novels and coming to terms with what had happened. (One of his earliest visitors was Bill Clinton, the former US president.) He pulled through, as it seemed, without lasting ill effects, though his doctors instructed him to eschew all public commitments for at least a year. Ever humorous, “the rest cure” was how Heaney described his stay in hospital. And as soon as the year was up he resumed his life of plentiful public engagements. His last appearance was at the Merriman Summer School in Lisdoonvarna, Co Clare, on 16 August; there, he and his friend and fellow poet Michael Longley gave a joint reading, to vast applause.

The year following his stroke, however, saw Heaney immersed in a new and different project. Stepping Stones, a series of extensive interviews with him conducted by fellow poet Dennis O’Driscoll, was published in 2008. Heaney, at 68, was in a position to take stock, to reflect on the past and all its implications. As in the poem “Aerodrome”, it was a case of

Bearings taken, markings, cardinal points,

Options, obstinacies, dug heels and distance,

Here and there and now and then, a stance.

Prompted by a thoughtful and intrepid interlocutor, Heaney came up with extraordinarily lucid, compelling and forthright answers to questions about his life and times, attitudes and angles of vision. Not an exercise in self-revelation, or a quasi-autobiography, Stepping Stones is rather a guideline to crucial events in its subject’s life, in both the public and the personal sphere (though the private core remained private, a necessary counterbalance to all the celebrated Heaney geniality and public acclaim). What shines through these interviews is the sense of a person of unprecedented gifts and equally rare integrity, as a poet, husband, father, friend and “mythologised public figure”.

When Heaney’s 12th collection, Human Chain, came out in 2010, Peter McDonald, writing in the TLS, hailed it as a work which “allows questions of death and rebirth, forgetting and memory, and parents and children, to set an agenda which the poems themselves both address and transform”. The same reviewer noted the book’s engagement with the Aeneid, the Virgilian underworld, though,- as he said, the poems are located “every bit as firmly in County Derry”. It is a pertinent observation: throughout his life Heaney remained true to his origins, to his experiences as part of a minority existing uneasily in the North of Ireland under Unionist rule. Nothing about his attitude was ever inflexible, though. During the Queen’s state visit to Ireland in 2010, Heaney was placed next to her at a formal dinner, despite the lines from “An Open Letter” asserting his Irish identity: “No glass of ours was ever raised / To toast the Queen”. He remained true to the concept of neighbourliness transcending sectarian imperatives, to the forked hazel-stick, the lamps swung though the yards on winter evenings, the cairns and drains and outlying fields and the sandstone coping of Anahorish Bridge. He forgot nothing, and took it all in. Because of him, the worlds of his childhood, of his exemplary life, of Northern Ireland, of literature in general, are immeasurably enriched. “And afterwards, rust, thistles, silence, sky.”

Seamus Justin Heaney, poet and teacher: Mossbawn, Castledawson, Co Derry 13 April 1939; Professor of Poetry, Oxford University 1989–94; Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory, Harvard University (formerly Visiting Professor) 1985–97; Ralph Waldo Emerson Poet in Residence, Harvard University 1998–2007; Nobel Prize for Literature 1995; married 1965 Marie Devlin (two sons, one daughter); died Dublin 30 August 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks