The rise of 'Dalit lit' marks a new chapter for India's untouchables

As caste divides fade, a fresh crop of writers is emerging

Ajay Navaria, a writer of novels and short stories, cannot help but laugh as he reflects on the nature of his "other" job teaching Hindu ethics and scripture at a leading university in Delhi. The 39-year-old is a Dalit, a so-called "untouchable", and little more than a generation ago, for him to have even been discussing Hindu texts would have been an offence that could have cost him his life. The fact that he now teaches them brings a smile to his face.

"Fifty years ago it would have been a crime. I think about this and think that if I had touched those scriptures I would have been killed," he says, perched in a booth in a decaying coffee house in Delhi's once grand Connaught Place. "But democracy has given me power. It has given power to the depressed classes and helped to make a more modern society."

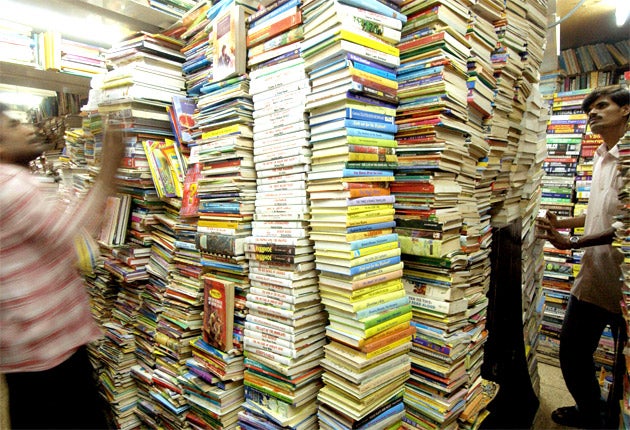

In his own way, Navaria is at the spearhead of a quiet cultural revolution sweeping India's literary establishment. Having long been confined to writing only in their own, local languages and largely ignored by the literary mainstream, Dalit authors are now being swooped on by some of the country's biggest publishers, such as Radhakrishna Prakashan which is translating their work into Hindi, the lingua franca of northern India and beyond.

Novelists, poets and writers of short stories are receiving both exposure and opportunity in the market-place that they have never before received. There are Dalit magazines, Dalit literary forums (there are two competing groups in Delhi alone) and Dalit workshops. And as further proof of the rising importance and clout of "Dalit lit", Mr Navaria was this year a guest at the influential Jaipur literary festival, an annual gathering and networker's paradise of Indian and international air-kissing types.

Indian society can sometimes seem harsh or even brutal. Nowhere is this more evident than in its caste system, a centuries-old hierarchy of categorisation based on ancient Hindu teachings that groups people into one of four main castes (and thousands of sub-castes). Traditionally, the caste someone belonged to decided where they would live, what job they would do and even what they would eat. People outside of these groups were considered unclean and not true Hindus, fit only for tasks such as cleaning toilets, making leather and sweeping the roads.

Dalits have suffered centuries of abuse and even today, despite legislation to protect them and an increasingly urbanised society, they are still the victims of widespread prejudice, discrimination and violence. A recent report by the Tamil Nadu Untouchability Eradication Front, a coalition of human rights groups in southern India, revealed a bewildering degree of discrimination, both in scale and form.

Among the various abuses detailed by the authors of the report, Dalits were not allowed to use a mobile phone in the presence of upper-caste people. They were also prevented from having their clothes washed, permitted only to drink tea from coconut shells while squatting on the floor, barred from entering temples, forced to eat faeces, raped and burned alive.

Yet Dalits total more than 150 million people – around 20 per cent of India's population – and the realisation has slowly come that with such critical mass, this community could have considerable leverage. In India's largest state, Uttar Pradesh, low-caste voters have on three occasions elected a Dalit chief minister, Mayawati Kumari.

The size of the population has also been a factor in the emergence of Dalit literature as publishers have woken up to the potentially massive market. As Navaria says: "They are doing their business, they are not missionaries. If they get a profit, they will do it. If they do not, then they won't."

A key figure in the emergence of low-caste writing is Ramnika Gupta. She is not a Dalit but she produces a quarterly magazine, Yuddhrat Aam Aadmi, devoted to previously marginalised writers. She estimates that she and her team of just three full-time assistants have published around 1,500 Dalit writers from across India over the last two decades. Large publishers regularly go to her for information about new talent. She helps on the condition that the publishers agree to produce a paperback edition that is affordable for ordinary people, in addition to the standard hardback run.

In the first-floor drawing room of her home, which also serves as her office, she noted that Dalit writers never lacked subject material. The highly influential writer and Dalit leader, B R Ambedkar, she explained, had said it was essential that low-caste people had their own literature and that they wrote about their own lives.

Mrs Gupta, who has herself written dozens of books on Dalit and tribal people's issues, said of the caste system: "India's culture discriminates. It's a state of exploitation. Everyone thinks 'He is lower than me' or 'I'm superior'. What we are trying to say is that we are all equal and if anyone is weak, we can help them to rise."

Dalit writers say the emergence of low-caste literature has taken place alongside a broader growth of consciousness and activism, particularly in urban India. While in rural India, caste remains all-pervading, in cities many of the signs and signals that identify a person's caste have vanished. In cities, too, Dalits are better organised to stand up for their rights.

"There is a growing consciousness that is emerging. People are now better educated and they all get to know about their rights," said Anita Bharti, a long-time writer and activist who heads a Dalit literary forum that meets every month in Delhi.

Literature, said Ms Bharti, has an important role to play in the ongoing struggle by Dalits to end discrimination. While abuse of low-caste people still happens, "they can now write about it. Also, people realise that Dalits have been mistreated in the past and that there is a need to bring Dalit literature to other people."

Navaria, who is now working on his second novel, agrees. When he wrote his first novel, Udhar Ke Log (People From That Side), he had no doubt that the main antagonist would be a middle-class, urban Dalit. The story tells of the various ways in which his low caste affects his life, including being rejected by his lover – herself a sex-worker – when she discovers he is a Dalit. "I chose to write about Dalit consciousness. I have felt myself treated like this many times," he says.

One of his most painful, burning experiences was as a schoolboy of 12 or 13 when scholarships were being offered to Dalit pupils. His teacher walked into the classroom and asked any low-caste pupils to stand up so that their names could be taken down. "I never stood up. I went to the head teacher later [to apply for the scholarship]," he recalls. "You feel so ashamed. One friend said to me 'You don't look like a Dalit'. I asked him, 'What do you think a Dalit looks like?'"

Navaria rejects the suggestion that by writing about purely Dalit issues and by knowingly organising themselves as Dalits, this new generation of writers is actually reinforcing caste divisions, rather than breaking them down. "If there are divisions in society, how can there not be divisions in literature? Publishers are not promoting these divisions but are reflecting them," he says. "Caste is very important. You cannot imagine India without caste. If a person says they are a Hindu, then they will have a caste."

One breakthrough these writers have yet to make is getting published in English. Partly that is because the writers prefer to work in a medium that their main audience can understand. But Ms Bharti and others say that getting the attention of the "elite" English-language media is still a challenge.

Navaria says he sees many obstacles ahead, but that he has the energy to overcome them. "Writing is not my profession, it's my passion," he says, as he finishes his coffee, Delhi's warm yellow sun slipping from the sky. "I cannot even sleep if an idea is in my head. For two or three nights, I cannot sleep until it's completed. It's a duty to the society."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks