A Slight Trick of the Mind by Mitch Cullin, book review: Sherlock Holmes is reincarnated - but is it convincing?

There is a current vogue for spin-offs from literary works which are so well-known that people scarcely bother to read the originals. Whereas Elizabeth Bennet tends to be reincarnated in a Regency romp, Sherlock Holmes, especially in his retirement as a Sussex bee-keeper, appeals to a more literary authorship.

Invariably, these versions soften his intellectual severity, equipping him with feelings unperceived by Conan Doyle. Laurie King has given him a teenage girl as a companion. Michael Chabon, who just refers to him as "the old man", introduced an adolescent boy. And Mitch Cullin endows him with a growing affection for young Roger, the son of his housekeeper (not Mrs Hudson – she is already dead.)

One wonders how Ian McKellen will portray Holmes in the forthcoming film of this book – what a contrast with Cumberbatch's young sex idol!

Cullin's Holmes is now over 90, trying to finish two works, The Whole Art of Detection and the ultimate treatise on bee-keeping, and conscious that his mind is slipping away. Lapses of memory, inexplicable incidents – the signs of incipient Alzheimer's are present, and Roger's interest in bee-keeping is a consolation. The present, of Roger and the bees, intertwines with two key past events; one is a mystery from the Watsonian past, The Glass Armonica, the other a more recent experience of a visit to post-Hiroshima Japan.

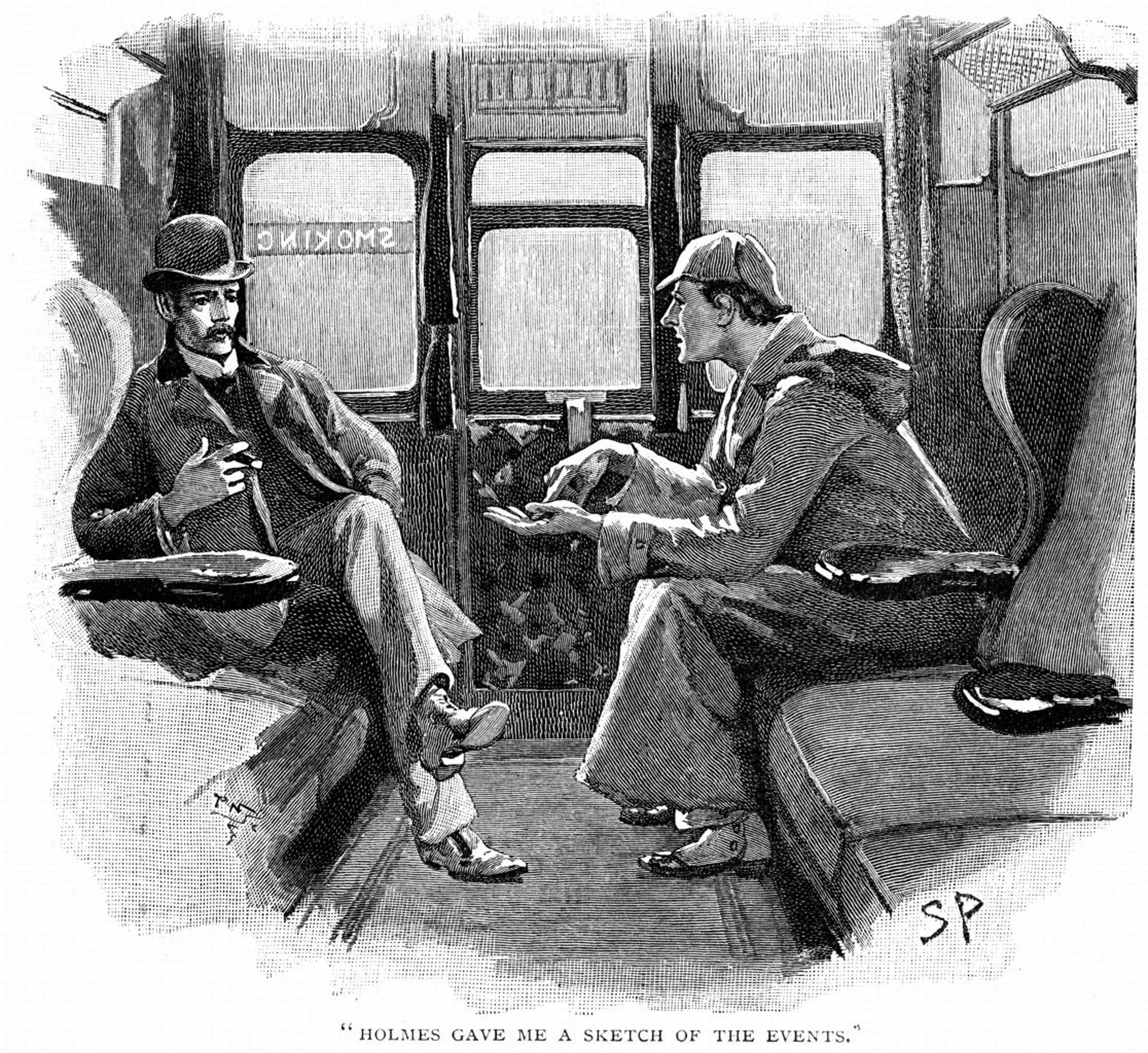

The book plays with levels of reality: this Holmes disavows Sydney Paget's version, the picture of "Sherlock-San" instantly recognised by Japanese admirers, and the persona in this novel is observedly less "extravagant and colourful" than Watson's account. It is a mistake, however, to leave Watson's narration and hand the story over to Holmes himself. Watson enabled Conan Doyle to obscure the image of the detective so that he appears as an almost superhuman presence seen through a mist of awe and astonishment.

Cullin's creation of a fuller human personality has too many sops to modern sensibilities: one cannot believe in a Holmes who cradles a dead baby, nor in one who calls women "dear". Watson was also an important narrative device, allowing Conan Doyle to move to a different viewpoint from that of Holmes, a shift which Cullin can only make with some clumsiness. The traditional mystery enshrined within the book is not much of a puzzle, nor is the cause of young Roger's death as deduced by Holmes.

When Cullin writes in his own authorial persona, however, the Roger story is extremely touching. Holmes' visit to a devastated Japan is powerfully felt, the suffering Japanese seen as individuals, not as some kind of semi-extinguished vermin.

But Cullin seems to use Holmes to write about whatever he wants, ranging from Hiroshima to glass armonicas (wine glasses filled with water to produce an ethereal sound). There is plenty of fine atmospheric work here to create a sense of period, and one wishes Cullin had abandoned the prop of Sherlock Holmes altogether. Unlike many authors of these "character reincarnations", he is surely capable of originality.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments