A Strangeness In My Mind by Orhan Pamuk; trans Ekin Oklap, book review

Orhan Pamuk’s novel about working-class urbanites is his most Dickensian yet

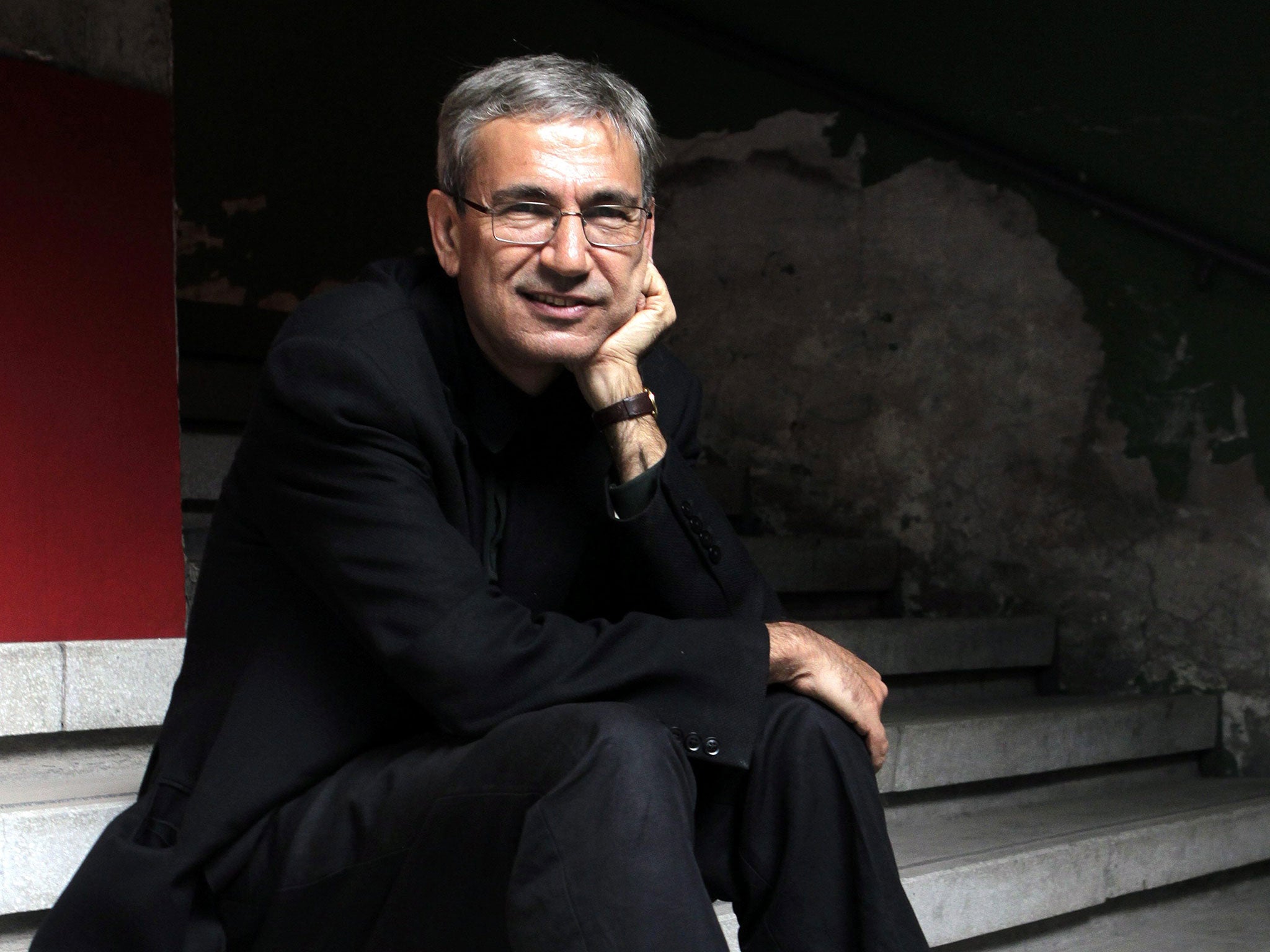

A drawing by Turkey's Nobel laureate in literature, who studied architecture and longed to be a painter, graces the cover of his ninth novel. It shows a young man looking out quizzically towards a close-packed, high-rise metropolis, a futuristic hive of towers and malls. Across the 600-odd pages of this epic fusion of soap opera, family saga and state-of-the-nation novel, Pamuk's beloved Istanbul mutates into that kind of skyscraping agglomeration: no longer a “familiar home” but “dreadful and dazzling at once”. Yet Pamuk drew that vision 20 years ago, before the advent of hyper-modern Istanbul. Here, as in his earlier books, we slide between a city of the streets and a city of the mind.

Never before has Pamuk placed the lives of working-class incomers from rural Anatolia so squarely at the centre of his work. Complete with family tree, chronology and even a character-index, A Strangeness in My Mind (the title comes from Wordsworth's The Prelude) recounts the adventures of Mevlut Karatas and his extended family between 1969 and 2012. From a village near Konya, they join the ever-growing ranks of poor but enterprising migrants whose hard work and traditional outlook have made Istanbul so much bigger, so much richer – but also more provincial and conservative.

This is fresh territory for the “Westernised” Pamuk, glibly labelled both in Turkey and beyond as the stereotypical liberal secularist. He plunges into Mevlut's mind and world with robust, big-hearted energy and empathy, finding shade and nuance in the deeds and views of those “new-money hicks from Anatolia”. Our hero's favourite job gives this time of transition its own bittersweet emblem. Although he also works as a chicken-and-rice vendor, cafe cashier, car-park supervisor, meter-reader and manager of a migrants' club, Mevlut loves above all to sell boza on the story-crowded streets.

“A traditional Asian beverage made of fermented wheat”, boza symbolises homespun warmth and old-school charm to citizens of the mushrooming metropolis. It also contains around three per cent alcohol: a fact ritually denied by pious Muslims. Sympathetically, Pamuk dismantles the either-or, us-and-them polarities that cloud perceptions of his native city, and country. Mevlut, who like his creator adores the “old things” still concealed in every nook of Istanbul, thinks that “Just because something isn't strictly Islamic doesn't mean it can't be holy”. Memory and custom have their sacredness as well.

The plot blends ancient and modern flavours. Thanks to a folkloric ruse, Mevlut elopes not with beautiful Samiha, whom he thought he was bombarding with ghost-written love-letters, but her smarter, plainer sister Rayiha. Kismet (fate) still lays down the law. The accidental couple come to love each other dearly, and with Rayiha's resourceful help Mevlut learns how to navigate the “secret world of the city”. Friends and family break into the boza-seller's story with their own chatty versions of events: a pseudo-documentary technique that carries into the finished novel traces of the grassroots research that nourished it. Ekin Oklap's high-spirited and reader-friendly translation keeps pace with Pamuk's fondness for colloquial chronicle and fairy-tale artifice.

Coups and riots come and go; Western fads eat into the street-vendors' trade; Istanbul spreads over its hills “like a monstrous creature... smothered in fog and factory fumes”. The “demon of change” races ahead, captured on the hoof in zestful episodes that tell us all about the dark arts of electricity theft, the ascent of slumland property-barons, or the economics of fast-food. The book sprawls as its city does.

With its comedy, sentiment, melodrama and voracious curiosity about the urban habitat, this is Pamuk's most Dickensian work. Still, as always in his prose, we return to the solitary protagonist wandering the haunted streets alone, a dreamer consoled by the conviction that “there was another realm within our world, hidden away behind the walls of a mosque, in a collapsing wooden mansion, or inside a cemetery”. For Mevlut, as for Pamuk, city and soul converge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks