Gandhi: Naked Ambition, By Jad Adams<br />Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence, By Jaswant Singh

At school in India, our history teachers told us the conventional narrative of India's independence, with the blame of the Partition falling squarely on the British. There was a clear hero – Mohandas Gandhi – and an obvious villain – Mohammed Ali Jinnah. We recognised our hero from our bank notes and from the name of the main roads. Gandhi was that ascetic saint who told us to respect everything, love everyone, and taught us that you could win over enemies through the power of moral persuasion. He sank the might of an empire in a fistful of salt. Richard Attenborough's 1982 film, Gandhi, shows that scene in its panoramic splendour.

In his engrossing biography, historian and broadcaster Jad Adams points out how the salt satyagraha at Dandi didn't exactly happen that way. "The great photographic image was a re-enactment for the cameras" of an event "on a muddy beach where the salt was not visible, and the act... less apparently symbolic," he writes. But symbols matter, and Gandhi understood that better than most, in particular the inept British rulers of that time.

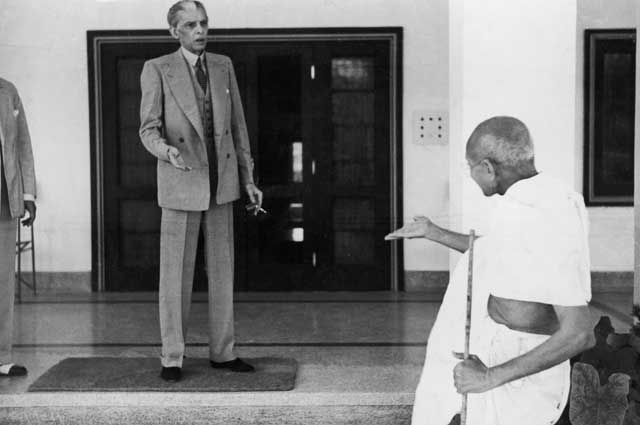

Adams's intent is to separate the myth from the man. He has some sobering insights to offer. In those Indian textbooks, Jinnah was the obstinate one: his persistence divided India. Jaswant Singh, expelled from the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party for writing this biography, shows that Jinnah, too, was a complex figure. In Pakistan, Jinnah is portrayed as a visionary who gave shape to the idea that Muslims of the subcontinent would survive and thrive only in a land of their own: Pakistan, home of the pure. That Jinnah liked the good life is glossed over, particularly after Zia-ul Haq's Islamisation of the country.

The orthodox narrative about Gandhi has also been simplistic, clearly delineating good and evil. In Pakistan, while Gandhi hasn't been sanctified, he doesn't receive the scorn reserved for other Hindu and Indian leaders. Gandhi had cunning, and critics say he cloaked political arguments in moral terms. But Gandhi fought the British, whereas the Congress Party fought the Muslim League. In Pakistan, Congress politicians were criticised for being devious; Gandhi, less so.

Adams focuses on Gandhi's ambition. The picture that emerges is not dissimilar to the image Indians have of Jinnah: of a stubborn man with strong views, some idiosyncratic, some wrong, some visionary. Adams has made substantive use of the copious paper trail Gandhi left behind and delved deep into his confessional prose.

Adams's book comes two decades too late. In the late 1980s, it would have shocked Indians, and nationalists would have found a reason to protest. But in the past two decades, India has moved further away from Gandhi. Its economy looks very unlike Gandhi's village-based ideal; its nuclear might is at odds with his pacifism. Challenging Gandhi's saintliness, while not commonplace, is no longer rare. A Marathi play sees Gandhi's life from the viewpoint of his assassin; a Gujarati play has shown his dysfunctional relationship with his sons. His grandson, Rajmohan, wrote a thoughtful and candid biography, at times critical.

More surprising is the nascent view in India that Jinnah was not after all a villain. This rethinking comes not from Indian Muslims, or those who seek better relations with Pakistan, but from the leaders of the BJP. In 2005 the BJP's then leader Lal Krishna Advani (a refugee from Pakistan) laid a wreath at Jinnah's tomb, extolling his secular views. Pakistan today has indeed drifted from Jinnah's vision.

One way to see Singh's book is as an attempt to undermine the reputation of Nehru, India's first prime minister. Singh sees Nehru's handling of the grave events of 1940s as selfish, mean-spirited and incompetent, leading to India's unnecessary division. As post-independence India has seen Jinnah only as a villain, Singh tries to get the balance right; he praises Jinnah's inclusiveness and federalist thinking. These conclusions are not entirely original; Stanley Wolpert and Ayesha Jalal have said similar things with, arguably, greater perspicacity and rigour. But Singh's account is unique in that it comes from an Indian, and a politician. The book is well-documented, although historians might find fault with some of his sweeping judgments.

Gandhi's fans won't like Adams's book – but they tend not to be fanatics, and no Gandhian is likely to issue a fatwa. Singh isn't as fortunate: not only was he expelled from the BJP, but the controversial chief minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi, banned the book. A court ruling overturned the ban, accidentally making Singh's biography a surprise best-seller in India.

Salil Tripathi is the author of 'Offence: The Hindu Case' (Seagull).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks