Ghostly, by Audrey Niffenegger - book review: Spiky social satire gives these chilling tale more bite

A wonderfully creepy collection of curated ghost stories

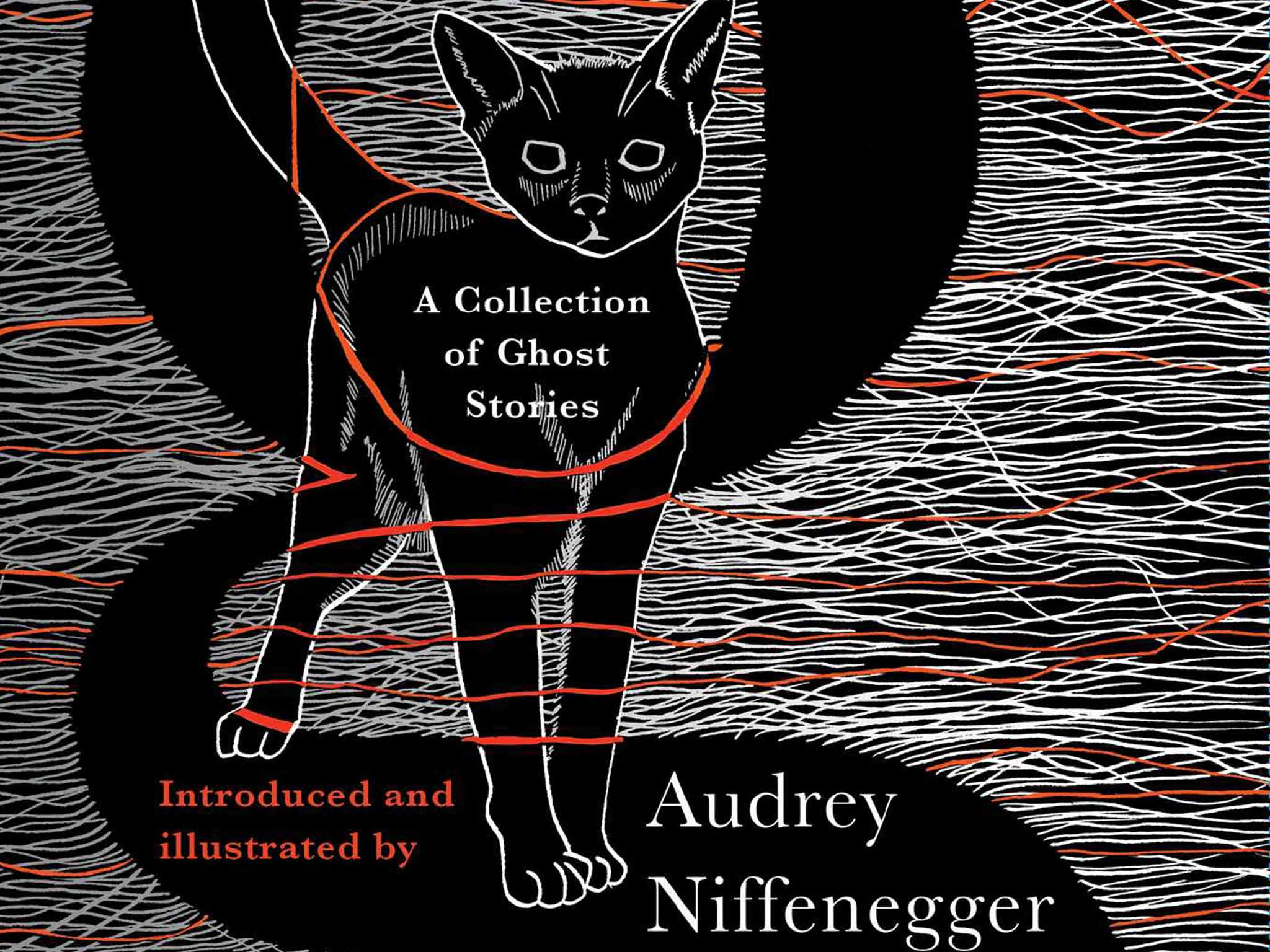

Audrey Niffenegger’s 2003’s novel, The Time Traveler’s Wife, sold nearly five million copies and was turned into a film by Brad Pitt. But she has continued to work on her own niche art projects. She wrote and illustrated the wonderful artist's book, The Three Incestuous Sisters (2005), and in 2013 published illustrated novella, Raven Girl, to accompany the ballet choreographed by Wayne McGregor. And now Niffenegger has curated and illustrated a collection of ghost stories - unusual, forgotten, previously unpublished - from writers including Edith Wharton, M.R James, Rudyard Kipling and Neil Gaiman.

She prefaces each story with a few personal lines - that make you see things you might otherwise have missed. There are clear themes to the collection - cats, children, houses (which can shelter us or go weirdly bad), unrequited love, bereavement. Each story seems to build on the one before.

Most are psychological mysteries; a few are spiky social satires. But all are about death. In her introduction to the beautifully designed book Niffenegger writes: “Ghost stories are speculations, little experiments in death… a literature of loneliness and longing.” In essence they allow us to play, safely, with the concept of inevitable loss.

And children with their stolen, unlived lives, make excellent ghosts, as Niffenegger observes. In A. M. Burrage’s Playmates (1927) a little girl schooled alone as a social experiment finds solace with ghostly peers. Both Kipling and AS Byatt experienced the death of a child in real life, so their stories are shot through with pain. In Kipling’s They (1904), a man stumbles across a house (based on Kipling’s own East Sussex property Bateman’s) inhabited by a blind woman and a group of children. Drawn back again to the enchanted spot, he realises he cannot inhabit grief forever.

Byatt’s modern-day The July Ghost (1982) sees a self-absorbed man offer to make love to his landlady after the death of her teenage son. It’s an exquisitely awful yet touching scene. “Sex and death don’t go,” she protests. “I can’t afford to let go of my grip on myself. I hoped. What you hoped. It was a bad idea.”

Babysitters - near strangers we let into our houses - are ambivalent. In Kelly Link’s The Specialist’s Hat (1998) motherless twins are lured into an attic, straight out of The Turn of the Screw. But in Gaiman’s Click-Clack The Rattlebag (2013), it’s the child who is chillingly creepy.

Romantic compulsion is another driver. In Wharton’s elegantly devastating Pomegranate Seed (1931) a woman in a late marriage realises her new husband is communing with his dead wife. While the novella-length The Beckoning Fair One by (George) Oliver Onions, 1911, is an extraordinary study of a man who fears flesh and blood women and tips over into obsession with a ghost. Is it actually a psychotic breakdown?

Several stories are very funny. Tiny “not-people” come through a portal in the bath in Amy Giacalone’s Tiny Ghosts and terrorise a working-class couple whose house is a shrine to Walmart (you’ll be glad they see off their snooty manipulators). Niffenegger discovered Giacalone reading in a Chicago bookshop - the story she says “seemed to jump in my lap and lick my face”.

And then there are the cats. Edgar Allan Poe’s The Black Cat (1843) is a classic revenge tale. But it’s Niffenegger’s Secret Life With Cats (2006) that left me reeling. Inspired by her time working at a cat shelter, it’s the story of a lonely housewife who escapes a husband who keeps remodelling their house.

At the shelter she is drawn to an older woman who later disappears. The final vision of a cat-filled basement “which smells of unbathed flesh, meat, baby powder” chills the soul. Is it a ghost story, a murder or a (veiled) love affair? Niffenegger admits she wrote it after being unfriended by a woman (interestingly in today’s slang dumping a friend or lover is called “ghosting’).

Niffenegger is happy to include un-PC writers. But she’s not embarrassed to draw a moral from these little experiments in death. Be kind, pay attention, don’t get carried away she advises. You never know what you are up against.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks