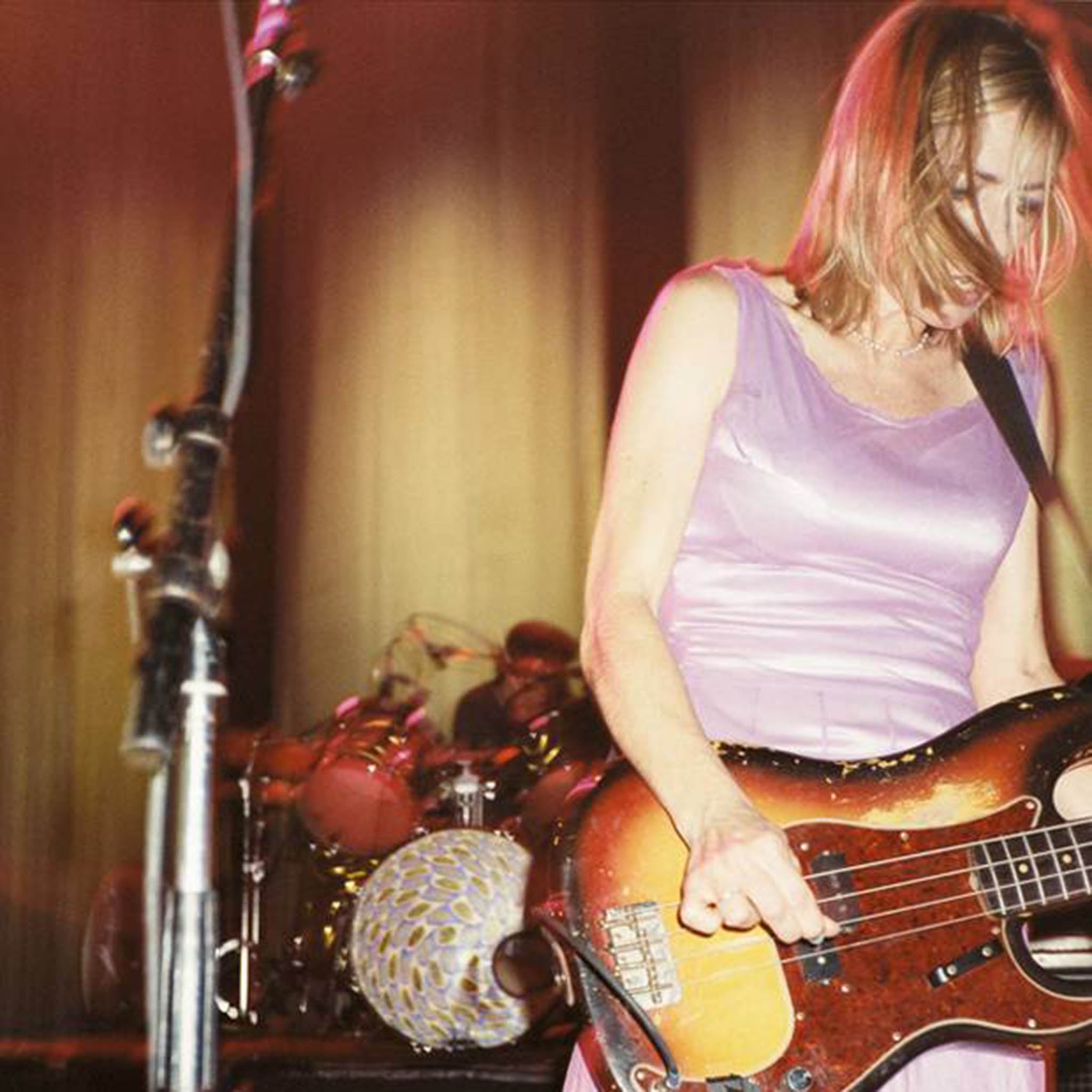

Girl in a Band: A Memoir by Kim Gordon; book review

When the post punk-rock group, Sonic Youth, disintegrated in 2011 following the break-up of the marriage of key members, Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon’s, bereft fans sought answers. This memoir, named after one of Gordon’s most hated interview questions (what’s it like...?) offers those answers, openly, and often bitterly. But first and foremost this is a book about Gordon’s life, from growing up in California, with years spent in Hong Kong and Hawaii to starting art school and moving to New York where her first job was working in a gallery as its inept assistant. You have to get nearly half way through the book before the story of the band even begins.

Gordon, now 61, first encountered music through her involvement with the conceptual art scene in Seventies New York. Her descriptions of her early twenties sound like a Who’s Who of the Seventies art scene - Jeff Koons, Gerhard Richter, Barbara Kruger, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Larry Gagosian were all involved in Gordon’s life, and the some of the juiciest bits are her snide asides about them (“No-one liked Jeff”” and Larry has a “complete absence of credibility as an art dealer”), but the name-dropping sometimes feels excessive, as the pages become lists of who she saw at which party in who’s loft apartment.

She was a conceptual artist first and fell into music because of the people around her. Her first attempts at being in a band were interactive art projects – one was Audience, Performer, Mirror, conceived by her friend, the artist and curator Dan Graham. Graham put Gordon together with musicians Miranda Stanton and Christine Hahn (with whom Gordon later formed a real, short-lived band called CKM) and they performed as Injection. During the performance, Gordon sang adverts from women’s magazines. One song was called: “Soft Polished Separates.” That one show gave Gordon the bug for performing. It was “as if I were a kid on a high-altitude ride I’d never had a ticket to go on before. I woke up the next day, and even though Injection had performed precisely one show, I told myself we were now officially on tour. This was surely what the Stones or the Yardbirds felt like the first time they played, I thought.”

She acknowledges that she’s perceived as “cold” on stage and in interviews but asserts she’s vulnerable underneath and as you read on that begins to ring true. It comes across in her descriptions of feeling awkward and out of place, her need to please the men in her life and the insights she shares on how women in the public eye still have to fit the “male gaze”:

“Female singers who push too much, too hard, don’t tend to last very long. They’re jags, bolts, comets: Janis Joplin, Billie Holiday. But being that woman who pushes the boundaries means you also bring in less desirable aspects of yourself. At the end of the day, women are expected to hold up the world, not annihilate it.”

Her early, pre-Thurston flings are glossed over, but with Moore it’s all laid bare. The bitter warning signs of his affair are spread out on the pages as though she’s dissecting them all over again.

She’s evidently still angry and as well as pointing out what he lacks as a husband and father, she also takes the opportunity to slam him artistically. “Thurston’s solo record, called Demolished Thoughts, was like a collection of sophomoric self-obsessed, mostly acoustic mini suicide notes,” she tartly notes.

Thurston is portrayed as a very flawed character who Gordon loyally stood by against her better judgement and she likens the experience to her childhood with a deeply troubled brother, Keller, who was the partial inspiration for Sonic Youth’s “Schizophrenia”. Keller manipulated her, but she nevertheless adored him: “I needed to believe he was larger than life, a distorted genius, declaiming and wild in white... Looking back, his sadism might have been a symptom of the disease that showed itself later,” she notes in one of many descriptions of how the divorce has forced her to re-assess everything through darker-tinted lenses.

The worst thing is the sordid mundanity of it all, which she captures with notes like: “The co-dependent woman, the narcissistic man: stale words lifted from therapy that I nonetheless think a lot about these days”, or by detailing the soap-opera way she discovered Moore’s infidelity from text messages on his iPhone. One moment in the early days of their romance becomes a metaphor for their relationship: “Once, when his stapler wasn’t working, he picked it up and threw it through the window, shattering the glass. It scared me... As creative as our relationship was, our marriage felt progressively lonely too. Maybe it got too professional. Maybe I was a person – like a stapler – who just didn’t work for him anymore.”

It’s a quotidian image and one that accurately sums up how a relationship, even that of a feminist role model and music legend, can easily crack.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments