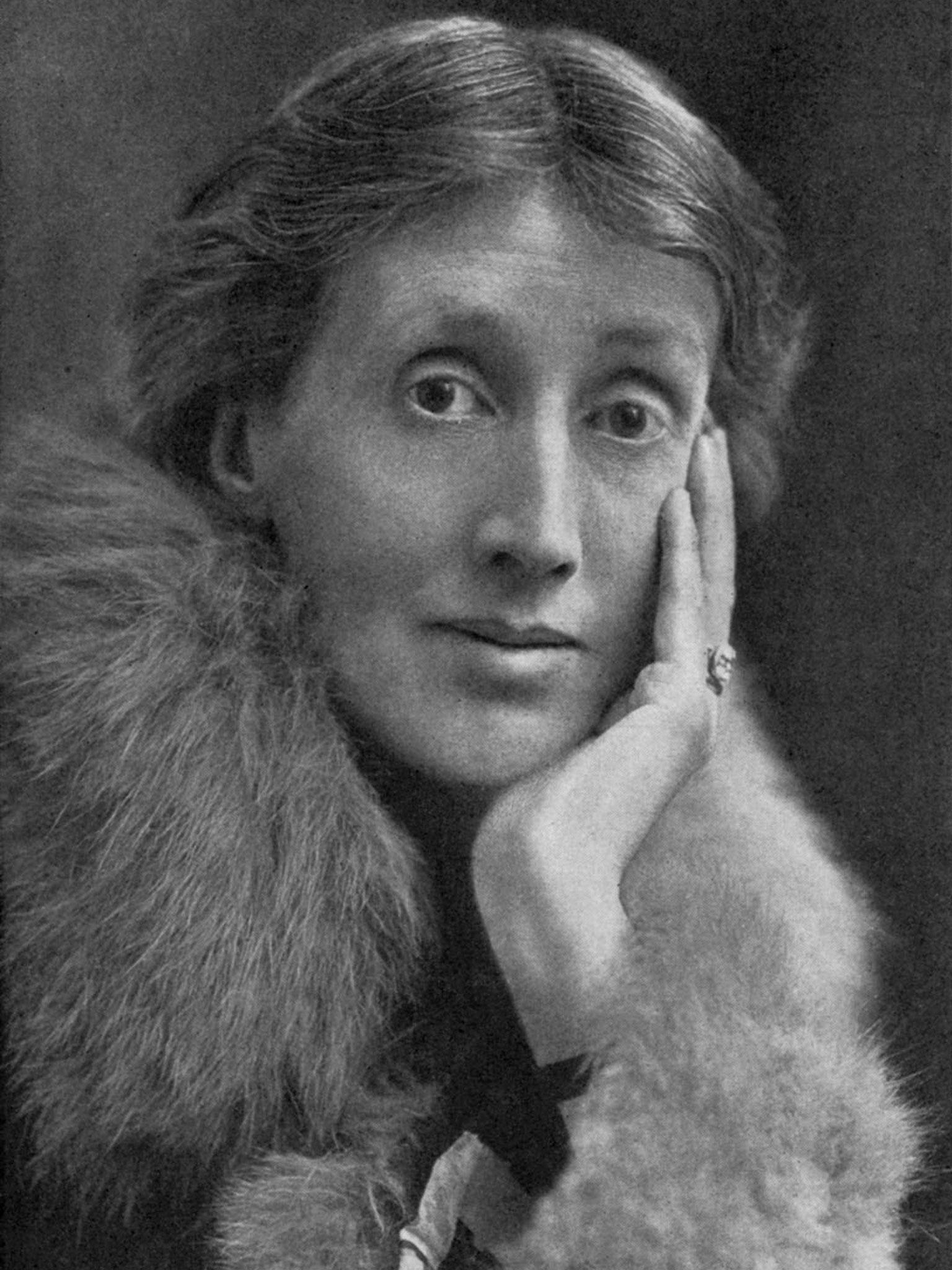

Having a press of one's own: Virginia Woolf's publishing preoccupations were our own

There are two rooms in the National Portrait Gallery’s Virginia Woolf exhibition which show, under glass, the beautifully designed covers of the books that Woolf published after she set up her own press with her husband, Leonard Woolf.

Visiting the exhibition, which re-constructs the author not just through portraiture but the objects that belonged to her (walking stick, letters, passport), it’s startling to see how her preoccupations with publishing chime with themes of our own age. She was, in effect, a self-published author –creating Hogarth Press for the purpose – and she also wanted the book to become a thing of beauty. Sound familiar?

She and Leonard sought a press of their own to escape the creative restraints of conventional publishing houses, and to produce books that more commercial publishers might eschew. They also decided to make covers beautiful.

Admittedly, this Bloomsbury couple are not quite equivalent to the self-published authors of today. Woolf’s debut and bildungsroman, The Voyage Out (1915), was published by her half-brother’s firm, Duckworth Press, so she was hardly struggling to get into print, though there is apparently evidence to suggest that she toned down passages on homosexuality, colonialism and women’s suffrage in this book, perhaps because of the conservatism of the publisher.

So they were rich and well-connected enough to start their own press, but all the same, it showed daring, and a liberating resourcefulness. Reading Frances Spalding’s book, Virginia Woolf: Art, Life and Vision, which accompanies the exhibition, it is clear that this venture was a labour of love.

“What catapulted them into action was the arbitrary sighting of a small hand-press in the show window of the Excelsior Printing and Supply Company, as they walked down Farringdon Street...It took them two months to create [their first] 34-page booklet, partly because they only worked part time on the press, but also because they did not have enough type to produce more than two pages at a time.”

They spent yet more time finding “beautiful, uncommon, and sometimes cheerful paper for binding our books” including Japanese print, patterned paper from Czechoslovakia, marbled paper made by Roger Fry’s daughter, Pamela, and woodcuts by Virginia Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell. There are ample examples of the results at the NPG: the marbled front of TS Eliot’s Poems (1919); the art deco style woodcut cover design for Virginia Woolf’s short story collection, Monday or Tuesday (1921), designed by Bell. The first book they ever produced is there – two short stories (one by Virginia, one by Leonard) with illustrations by Dora Carrington. And so are the first, very pretty editions of To the Lighthouse (1927), and Mrs Dalloway (1925).

Transforming the book into an aesthetic, covetable physical object is just what they achieved.

We are seeing some small publishing houses do daring things and triumph against the odds – Galley Beggar, which published the experimental, Baileys Prize-winning novel, A Girl is a Half Formed Thing, is one – and we are also seeing lavish publishing ventures such as Notting Hill Editions that bring out books to be kept forever and treasured. The Woolfs would surely have approved. The exhibition at the NPG, which is on until 26 October, proves it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks