I & I: The Natural Mystics - Marley, Tosh and Wailer, By Colin Grant

As a biography of the Wailers, "undisputed kings of reggae", this is a pretty good history book - as was Colin Grant's previous work, on Jamaica's first national hero, Marcus Garvey. An apt link is that Bob Marley's "Redemption Song" quotes a Garvey speech from 1937: "We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery... none but ourselves can free the mind."

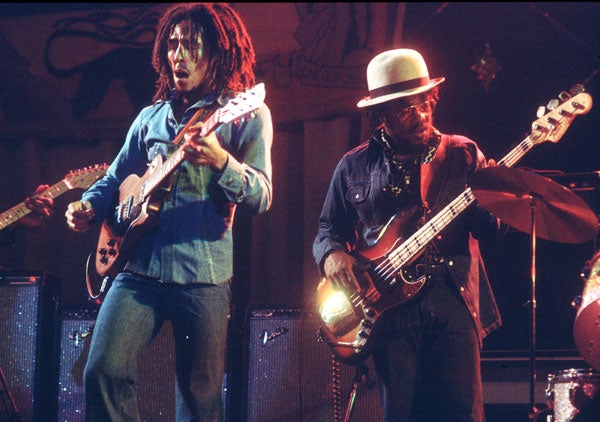

The mission of I & I: The Natural Mystics is to provide insights into the development of three young men who within a decade went from force-ripe countryboys to streetwise ghetto-dwellers to international music stars until their split in the mid-1970s. The trajectory was told in their evolving names: The Teenagers, The Wailing Rude Boys, the Wailing Wailers, and ultimately just The Wailers.

Grant's forte is setting the socio-political context that nourished and influenced them. He gives us lessons on the Frome Rebellion in 1938, a defining moment in Jamaica's colonial story; on the symbolic legacy of Garveyism; on the island's relationship with Britain and Empire; on Emperor Haile Selassie and the Rastafarian movement; on the banning of Guyanese academic Walter Rodney; and much else.

In terms of new information, others have already mined what is most accessible. The impoverished childhood, success in talent shows, the rip-offs by producers, the internal feuds, the seeking after spiritual truth are themes no less intriguing for being repeated, and the familiar trailblazing recordings no less impactful: "Get Up, Stand Up", "Nice Time", "War", "Simmer Down", "Stir it Up". Still, there are illuminating details and fresh revelations, as when Marley's muse Esther Anderson explains the controversial origins of "I Shot the Sheriff".

The shifting musical and personal dynamics are fascinating. Neville "Bunny" Livingston (he later changed his surname to Wailer) and Robert Nesta Marley were not just village neighbours; Marley's mother had a child with Wailer's father. In Kingston's Trench Town where they formed the nucleus of a band, Marley, Tosh and Wailer really were dirt-poor. When they later sang, "Cold ground was my bed at night and rock was my pillow too," it was not poetic licence.

The prickly Peter Tosh, who had fashioned his own guitar, could bring a session to a premature end by taking his instrument and going home. Thus far, Tosh was first among equals; but it was the elevation of Marley above the others, after the Wailers signed with Chris Blackwell of Island Records, that brought about the end – as if reggae was down to one man.

On Marley's death from cancer at the age of 36 in 1981, Peter Tosh was asked for a reaction. Well, if it so it just so," he said. "At least it leave a little space for all of us to go through now." Tosh himself died in 1987, shot by robbers who had targeted his house.

Grant argues (not entirely convincingly) that the three original Wailers represent ways of being for black men in the late 20th century: accommodate and succeed (Marley, his mixed race more acceptable to the mainstream); fight and die (Tosh, scary-looking tough guy in shades) or retreat and live (Wailer). That aside, in their different personalities were the seeds of their success and disbanding.

Interspersed throughout is Grant's own journey through the social layers of Jamaica, on the trail of the last man standing: Bunny Wailer. The changing fortunes of the elusive grey-bearded patriarch, now in his sixties, open and close this joint biography. In December 1990 at a festival in Kingston billed as "The Greatest One-Night Reggae Show on Earth", Wailer was one of 40 bands billed, the main attraction being a showdown between ragamuffin DJ Shabba Ranks and his rival for title of King of Jamaican Music, aka. Ninja Man. Wailer's contemplative start did not impress the crowd. In fury, he stopped playing but asked: "Don't you know who I am?" The answer was pelted bottles and cans.

Grant in turn poses a question for his book to answer: "if reggae music had delighted and enthralled so many around the world, transformed a tiny island into a musical superpower, and given a platform to the Wailers, a trio of extraordinarily poetic and powerful natural mystics, then how could it, in the space of 30 years, rise and fall so spectacularly and end so brutally?" Bunny Wailer, the reclusive survivor, became his quarry, a riddle to be solved. Several trips to Jamaica failed to track him down. Grant is at last accorded an audience with the man - at Gatwick airport. It takes no more than the final three pages of the book to report a happy ending, of sorts.

Margaret Busby edited 'Daughters of Africa' (Ballantine Books)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks