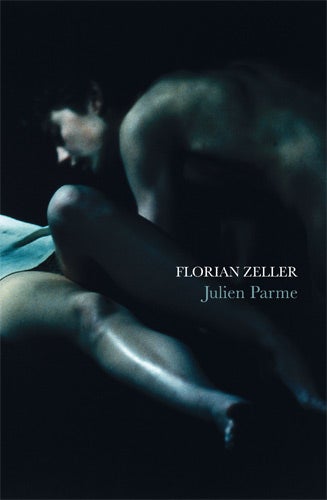

Julien Parme, By Florian Zeller, trans by Christopher Moncrieff

A classic tale of a misunderstood French teen

Julien Parme is 15 – well, nearly 15 – and destined to be a great writer. Trouble is, his mum insists on treating him like a kid and has shacked up with a creep called François who has a "de" in front of his name and, horror of horrors, wears corduroy trousers. Worse, François has a snooty, tell-tale teenage daughter, Bénédicte, who lives with them. Julien fantasises about his sexy French teacher, but reserves his idealistic love for schoolmate Mathilde. He can't wait to meet her at her sister's party, but after he gets caught smoking at school, his mother forbids him to go. Outraged, he steals his stepfather's bank card and embarks on a breathless nocturnal escapade through Paris.

This fourth novel by an award-winning French writer is a tour de force of literary ventriloquism. Julien is as unreliable a narrator as we are likely to come across, telling as fact things he contradicts, regaling us with fantasies in which, a few pages later, he has come to believe. His sufferings are as epic as his ambitions – like Hamlet, he wails: "My mother couldn't love this bloke. Next to my father there was no comparison."

His self-image as a writer seems as chimerical as his claims to sexual experience. His every attempt to write gives way to daydreams about his photo on the cover, and interviews with women journalists eager to sleep with him. Boasting of his literary knowledge, he reveals its flimsiness: he thinks L'Assommoir is by Balzac.

Yet in his seething ambition, ruthlessness and self-justification, Julien does indeed resemble one of the young men who populate much classic French fiction. His name is an elegant clue: Julien Sorel is the egotistical hero of Le Rouge et le Noir by Stendhal. Florian Zeller allows a chink of light to penetrate the edifice of Julien's self-regard when his hero reports an eavesdropped conversation between his mother and François. To him, it is indisputable evidence of their nefarious intentions; to the reader, it sounds like a sane discussion between concerned adults about a difficult and sometimes threatening adolescent.

But Julien never quite sacrifices our sympathies and, thanks in part to Christopher Moncrieff's stylish, street-smart translation, the reader is completely caught up in his adolescent longings, his sense of boundless possibility and danger, and his desperate need to construct a place for himself in the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks