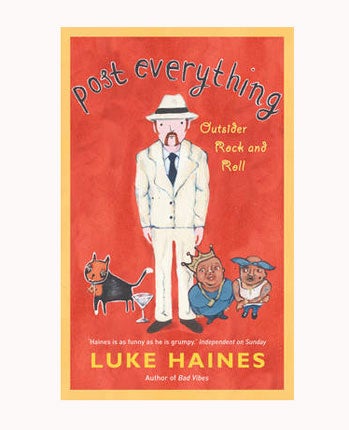

Post Everything: Outsider rock and roll, By Luke Haines

Memoir of a not-so-hot property

Even fans might be surprised that singer-songwriter Luke Haines has produced a second volume of recollections of his musical career (one more than Keith Richards, Miles Davis or Mark E Smith), especially as this volume ends in 2005, suggesting that yet another instalment might be on its way.

But Post Everything is written with such authority that it suggests that Haines has finally found his calling: indeed, it's almost as if he's deliberately sabotaged his career until now to give himself something to write about.

Post Everything picks up Haines's story in 1997. He claims it's about becoming an "outsider artist" but the true outsider is not a success who then drifts off to the margins, but an artist who always records and releases far from the public eye. Haines has put out 13 albums on sizable labels, remains a treasured cult figure and has written at least one hit single. From the outside, he looks like a man who has enjoyed as close to a regular gig as the music business can provide. As much of the book concerns big deals for projects Haines himself sees as unlikely to recoup, it's hard to see him as the marginal man.

Haines sees himself as too clever for music, but the music he likes (Black Sabbath, Billie Piper, Status Quo) is mostly dumb. He has a killer knack for the cruel put-down – people who end up on the wrong end of his tongue include Chrissie Hynde (for calling him a Nazi), Glenn Hoddle (for his stupid comments about disabled people and karma) and, bizarrely, Don Warrington from Rising Damp (for looking disgusted when Haines drunkenly eats a hot dog in front of him).

But the book's best sections are concerned with genuine failure. After finally drifting away from the music business, Haines decides to write a musical called Property for the National Theatre. He brilliantly describes two years of futile effort, and the true pain of collaborative endeavours. Although he has changed the names of most people involved, the anguish it caused him is clear, and it turns out the only thing Haines dislikes more than people going along with his ideas is people who resist them. After so many years of getting away with smuggling avant-garde concepts onto vinyl, he suddenly meets resistance, and it hurts. But Haines's pain provides our pleasure: if Property had succeeded, this book might have seemed mere boast.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks