Ryszard Kapuscinski: A Life By Artur Domoslawski, trans. Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Poland's superstar reporter led a double life – but does it detract from his achievement?

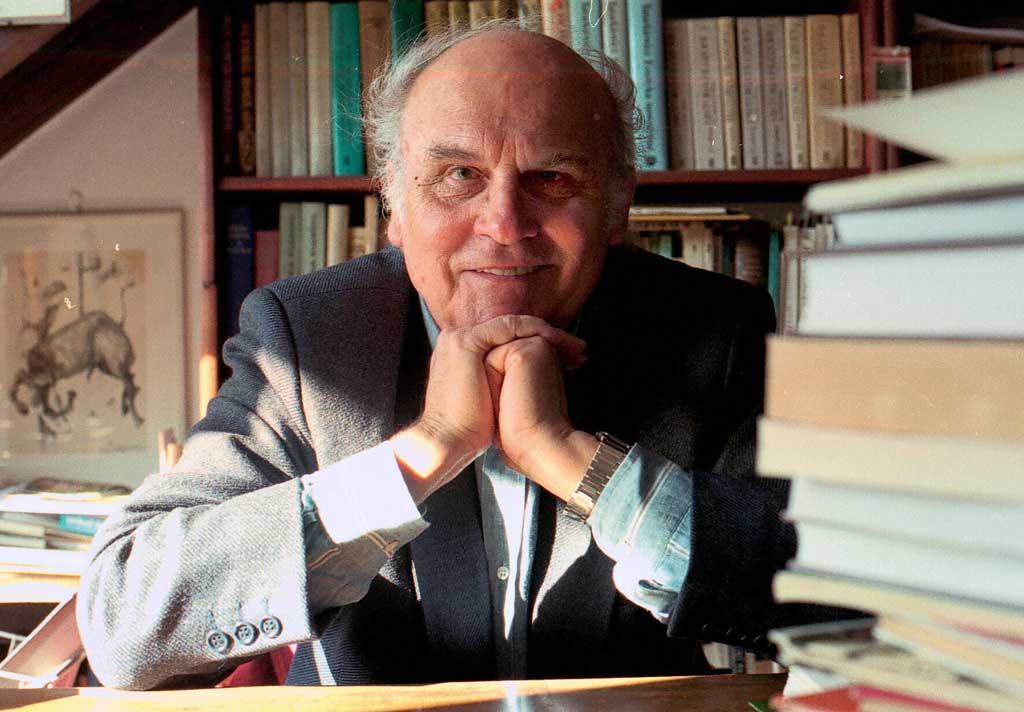

In its native Poland, this book has the English title "Kapuscinski Non-Fiction". That inspired contrivance has been replaced in the English version of the Polish journalist's biography by a generic formula that admits no hint of the tense ambivalences inside. Ryszard Kapuscinski cast a spell upon readers around the world as a reporter with transcendent literary gifts.

In his later years, and since his death in 2007, his reputation has been challenged by questions about his relationship with the facts and with his country's security services. This book is the first comprehensive reckoning.

It could even have been entitled "Anti-Kapuscinski". Although not hostile or malicious, it refuses to adopt the strategy favoured by its author's friend and mentor. Kapuscinski's books asked questions that they left unanswered, but they were stylistically resolved. The harmony of the composition counters the disturbance aroused by his accounts of war and the physiology of power.

Artur Domoslawski does the opposite. Trapped in the task he has set himself, he never spares his readers his discomfort and dismay. He fires off questions like distress flares. He is dedicated in pursuit of evidence, crossing continents to get it, but a reluctant judge. Instead he leaves the surfaces unsmoothed and the edges jagged. He has shortened the text for the English translation, largely by cutting quotations from articles, but the excisions do not substantially alter the picture. Above all, it remains clear that whatever else he may have been, Kapuscinski really was a communist.

When Kapuscinski broke through in the West with his book about Haile Selassie, The Emperor, it was recognised as a way to reflect upon power in his own country, where frank political discussion was impossible. In the 1970s criticism had to be roundabout – and Kapuscinski produced one of the most trenchant critiques of the period by going via Addis Ababa.

By the time The Emperor came out in English, the Solidarity trade union movement had emerged, gathered most of the nation under its banner, including many communist party members, and had been repressed by martial law. It was natural to take Kapuscinski for an oppositionist. But he only returned his party card after the clampdown, and hung on to the socialist ideals that had drawn him towards the scenes of armed struggles in the Third World.

He was used to overlooked places in indeterminate regions, having spent his early years in what were then Poland's eastern border marches. As a young man in Warsaw, he became an activist in a communist youth organisation in the early 1950s – during the Stalinist period, a fact he obscured in later life. He was a zealot, dedicating articles and even poems to that stilted cause. But he made his mark during the post-Stalinist thaw by setting the heroic clichés aside and reporting on the squalor of conditions in Nowa Huta, the concrete showpiece of socialist industry. His purpose was not to undermine the foundations further, but to see socialism built properly.

The system proceeded on the assumption that this could be achieved by pouring concrete and pronouncing slogans of a similar density. Kapuscinski continued to believe that if the cause was not a movement, campaigning and struggling, it was nothing. He roamed abroad to find new fronts, in Africa and Latin America, where the revolutionary spirit was being renewed. In those parts, working solo at ground level, he made himself one of a kind.

At the same time he was neither neutral nor independent. In Angola he learned that Cubans were assisting the leftist MPLA, a development that could have provoked Western intervention, but kept quiet about it. According to a former combatant, he carried a gun when in the field with MPLA fighters; by his own account, he fired it too.

As well as filing reports for the Polish press agency, he supplied briefing reports to the Polish security services. When this came out it was explained as the price of permission to travel abroad, which is true, but only part of the story. Kapuscinski's actions were consistent with his commitment to what he saw as a just cause, and to a state that he considered legitimate because of its own commitment to that cause.

Yet they were not open, and his sources were opaque too. The Emperor read like a fable, its courtiers speaking as their counterparts in Europe would have done centuries earlier. Its strategy of allusion allowed it to illuminate the murky discourse of a Soviet satellite state, but Ethiopians were entitled to feel that this had been done by making a mockery of their society.

One of Domoslawski's interviewees compares it to the Arabian Nights. Others are more sympathetic to Kapuscinski's elasticity, but there is no real defence. Sure, untruths can be used to construct a "higher truth", but you have to say that they are untrue and label it fiction.

Kapuscinski's modus operandi was based on combining journalism, literature, facts, fiction and political sympathies. In Polish idiom, "combining" refers to arranging things through combinations that are not necessarily legal, open or proper. He combined a long marriage with a career as a ladies' man. As well as collaborating with the security services, he maintained relations with the regime under which he had been raised, praying to the Virgin Mary when facing death, and taking Holy Communion when opportunity presented.

Another good title for this book would have been "The Kapuscinski Complex". Both the text and its subject are tissues of complexes, striving to construct themselves out of their own insecurities. Despite his courage in combat zones, Kapuscinski emerges as thin-skinned and under-confident. Being a reporter wasn't enough for him: he sought reassurance from being acknowledged as a literary figure and a thinker as well. Criticism unnerved him. He would have been devastated by Twitter.

Wanting to be liked, he made people feel that they were interesting and special. I can vouch for this: I met him once and that was exactly the effect he had on me. I was grateful then, and after reading Domoslawski's reckoning my feelings have warmed again. For after years of ominous hints, it appears that although Kapuscinski's transgressions were legion, they were low-level. He spun false impressions rather than flagrant lies. He did not persecute people when he was an activist or endanger people when he reported to the security services. The open questions teem around him; but that's inevitable when a man has spent so long in so many foreign countries, including one of the vanished European "people's republics", the most foreign of them all.

Marek Kohn's most recent book is 'Turned Out Nice' (Faber)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments