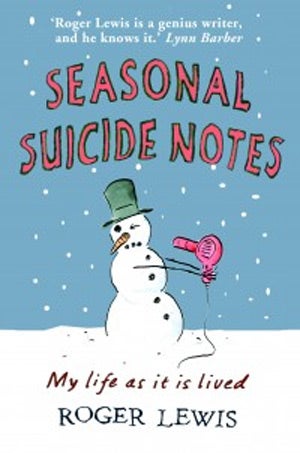

Seasonal Suicide Notes, By Roger Lewis

Comic tirade against philistinism

At first sight, the splenetic author of this gloriously funny book would seem to be an unlikely admirer of St Ailred of Rievaulx. Roger Lewis describes the abbot's two immortal Latin texts as "riveting". They are indeed riveting studies in tolerance and true compassion, written in the 12th century by a man who inspired love in everyone he met.

Lewis would argue that Ailred had it easy, living in a time of plagues, wars and colossal infant mortality. At least he didn't have to go on a cruise up the Amazon with Rosie Boycott and Maureen Lipman, or suffer the put-downs of "sad mother" Julie Myerson and historian Andrew Roberts, with his "grimace of a baboon with diarrhoea", or breathe the same fetid air as Piers Morgan, Simon Cowell and the titanically mammiferous Katie Price. Despite the lack of heating in the Yorkshire monastery, Ailred's warmth of feeling for others, and theirs for him, was a source of lasting happiness.

Lewis, resident in a former convent in the "Herefordshire Balkans", can only be said to be happy when he's at the circus or watching old recordings of the mesmerisingly dull soap opera Crossroads. On most days, as the rain falls on the Welsh borders, he is disgruntled and angry to the point of apoplexy with publishers, literary editors and the London literary scene in general. He rages against the cultural philistinism all about us.

One of the real pleasures of this grumpy collection of annual round-robin letters is in trying to ascertain where and when fantasy takes over from the truth. The family's housekeeper, a woman of limitless malevolence named Mrs Troll who makes Mrs Danvers look like Pollyanna, is a masterly comic creation. She would kill any pet who widdled on her carpet. Yet what Seasonal Suicide Notes also makes clear is Lewis's devotion to his saintly wife, Anna, and the freedom he allows his three sons to live their lives. The book is consistently hilarious, but has a certain poignancy too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks