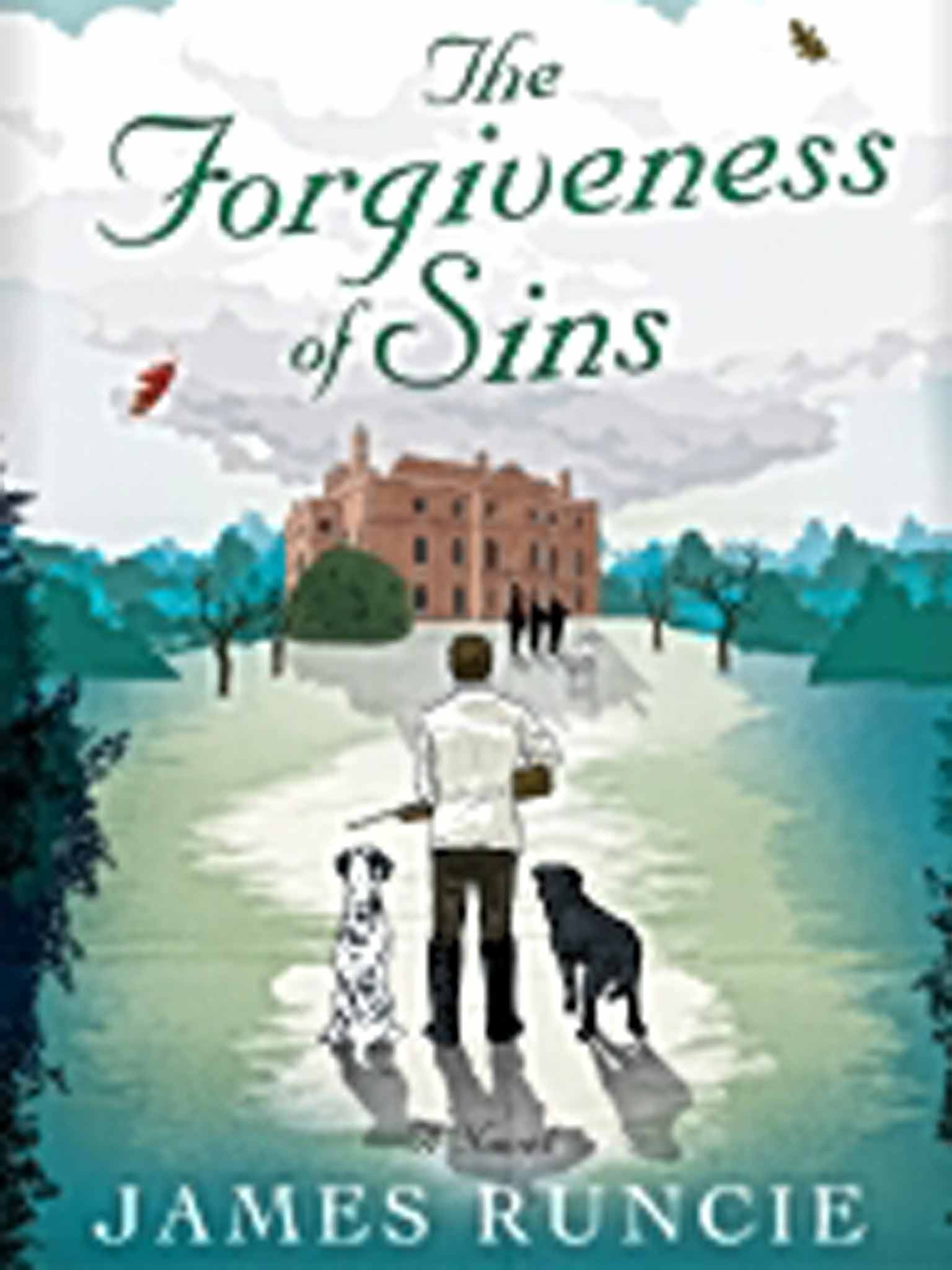

Sidney Chambers and the Forgiveness of Sins by James Runcie - book review: A delicious return for Grantchester's golden boy

It's no surprise that, after the rise of the serial-killer novel, which revels in gore and violence, there seems to be a yearning for the delights and comforts of the Golden Age in crime fiction. Although the fourth of James Runcie's Grantchester Mysteries – featuring his priest and part-time sleuth Sidney Chambers – is not set between the wars (the heyday of the Golden Age) there is a great deal of nostalgia to be found here.

The first of the six stories opens with a nod to the locked-door mystery, one of the tropes of the genre. A man wakes up in a Cambridge hotel room and sees his wife's bloodied body with a knife next to her and assumes he must have murdered her. By the time Chambers – a charming and handsome canon, now married and with a young daughter – has finished his investigation he reveals the truth of the matter to be more complex and morally disturbing than one might expect. As the name of the title story suggests, the theme of the book is "sin" in its many guises, and its forgiveness.

The author – who is the son of Robert Runcie, the former Archbishop of Canterbury and the model for Sidney Chambers – writes with warmth and insight about the tricky questions facing individuals in a post-war, godless universe. To what extent should you express personal freedom or should certain desires be curtailed? Do you have ultimate responsibility to yourself or to society? Is revenge for a crime ever forgivable? Who is best placed to mete out the most appropriate punishment? And what is the best way to live a happy life? "It's an Anglican Father Brown, Morse with morals," Runcie has said of the series, which opened in 1953 with the first book and which he intends to take up until the early 1980s.

Runcie is expert at exploring the fallout of betrayal, infidelity and the loss of a child. Issues such as wife beating and paedophilia are also explored in these new stories, set between 1964 and 1966. And while most of the historical detail is subtle and skilful, there are a few occasions when Runcie's social signposting is a little too forced and heavy-handed. But this is just a minor quibble.

Runcie works his magic using simple sentences, archetypal characters and a sense of suspense that creates an atmosphere of delicious anticipation. "Orlando Richards had never imagined that he would be killed by a piano falling on to his head," runs the opening line of Fugue. In Nothing to Worry About, Sidney, feeling slightly intimidated by a visit to an aristocrat's country home, remembers his mother telling him, "it's not all jam at the big house". And so it proves.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments