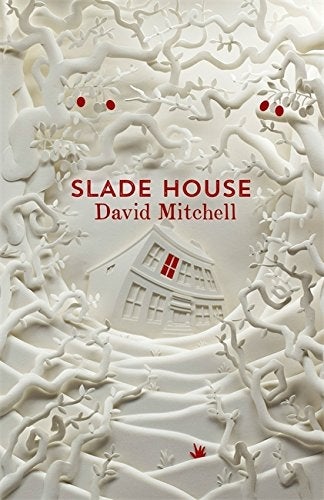

Slade House, by David Mitchell - book review: It’s not just the floorboards that creak in this haunted house

Sceptre - £12.99

Home is where we ought to feel safest, so no surprise that there are several haunted houses in the mix this Halloween. David Mitchell’s Slade House joins Guillermo del Toro’s film Crimson Peak and Peter James’s thriller The House on Cold Hill, being set in a mansion which, initially seductive, proves nightmarish.

Once again, Mitchell plays with interlocking stories and times as if fiction were a Rubik’s Cube. The first section, “The Right Sort”, began as a short story on Twitter in 2014, and is narrated by Nathan, a bullied boy accompanying his embarrassing mother to a gorgeous garden and house whose entrance, off a narrow, slummy alley, seems as mysterious and magical as that to Wonderland or Narnia. High on his Mum’s Valium, Nathan embarks on a game of Fox and Hounds with Jonah, a curiously old-fashioned boy the same age as himself. In the Twitter story the drug, which “breaks down the world into bite-sized sentences”, worked within the parameters of the form and provided an explanation for some terrifying visions.

In Slade House, however, the story is re-written, and set in 1979. The Valium is still there, but the visions are produced by soul-sucking “atemporals” – twins who, every nine years, must tempt mortals into the timeless bubble of Slade House in order to feed on their life-force. It’s a gripping premise which becomes increasingly suspenseful as the stories move closer to the present day. What the twins do in creating their seductive time-bubble is not dissimilar to what Mitchell does in luring readers in, and not letting us go. Be warned, this is not a book to read before bedtime.

Mitchell deploys his gift for creating convincingly realistic characters who rapidly command our interest and sympathy, but who turn out to be not always what they seem, and who, once again, have links to previous works. The next victim is a policeman, whose sexual vanity, greed and materialism make him easy to dislike – but whose sense of humour and responsibility make him more than the easy prey which almost deserves his gruesome fate. Each time, the reader hopes the victim will escape. Each time, the nastiness inches up, before the trap snaps shut. As in fairy-tales, those who eat or drink anything are doomed, yet just enough of the personality of previous victims remains to try to warn the next. One of the most chilling moments comes when Nathan sees a woman mouthing “‘No, No, No; or ‘Go, Go, Go’” behind a window, a warning he ignores. This is, as the best kind of ghost story shows, much scarier than the actual physical assaults. The diabolical cleverness of the predatory twins evokes a sense of dread as four out of five of the narrators are captured. Things “fall down the cracks”, however, and when the ghost of the policeman hands his successor a real knife, something starts to change. The climax gives us a showdown which surprises, satisfies and horrifies anew.

Mitchell’s characteristic is to play with fiction in order to ask questions about time, identity and temptation rather than give us a linear narrative. He is above all a great storyteller, and if his modish mash-ups produce concepts that are familiar to fans of Christopher Nolan’s Inception (and indeed Dr Who), what emerges from the dazzle is less subtle and more morally didactic than it might be. Combining horror with science-fiction has been familiar ever since HP Lovecraft and AE van Vogt; Mitchell’s gift for inhabiting different characters sharpens our engagement with his entertainment, but whether Slade House is great literature is debatable.

A great ghost story has to do something more than create a memorable atmosphere of increasing menace – it must also do something original with the form. When Henry James introduced doubts as to the narrator’s sanity in The Turn of the Screw, or Susan Hill provided a motive for the unlimited supernatural malignity of The Woman in Black, they produced works which advanced the nature of the ghost story itself. The grandeur of the classic haunted house is, in a sense, that of the genre itself as it wrestles with its own past. Here, Mitchell is revisiting the same ground he trod in The Bone Clocks, asking what we would do if immortality came at the price of “decanting” the soul of another and using up its energy as our own. (In The Bone Clocks, they need to do this every three years, not, as in Slade House, every nine. If you are going to create an inter-connected fictional universe you should, really, stick to your own rules.) Given that Cloud Atlas was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and that Mitchell is widely regarded as a formidably talented literary writer, it is disappointing to find that the haunted house that he has created is less of a mansion and more of a cottage.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments