The Infidel Stain by M J Carter, book review: Victorian sleuths hunt cold killer and hot curry

If this series is not bought for film, it would be another mark of the corporate stupidity that lost the BBC Ripper Street

We all love a bromance, and never more than in a detective novel. M J Carter’s second outing for her Victorian sleuths, Blake and Avery, draws on that of Holmes and Watson, but she is also one of a growing number of literary novelists whose plot and pace are burnished by stylish writing and specialist knowledge of a particular period in history.

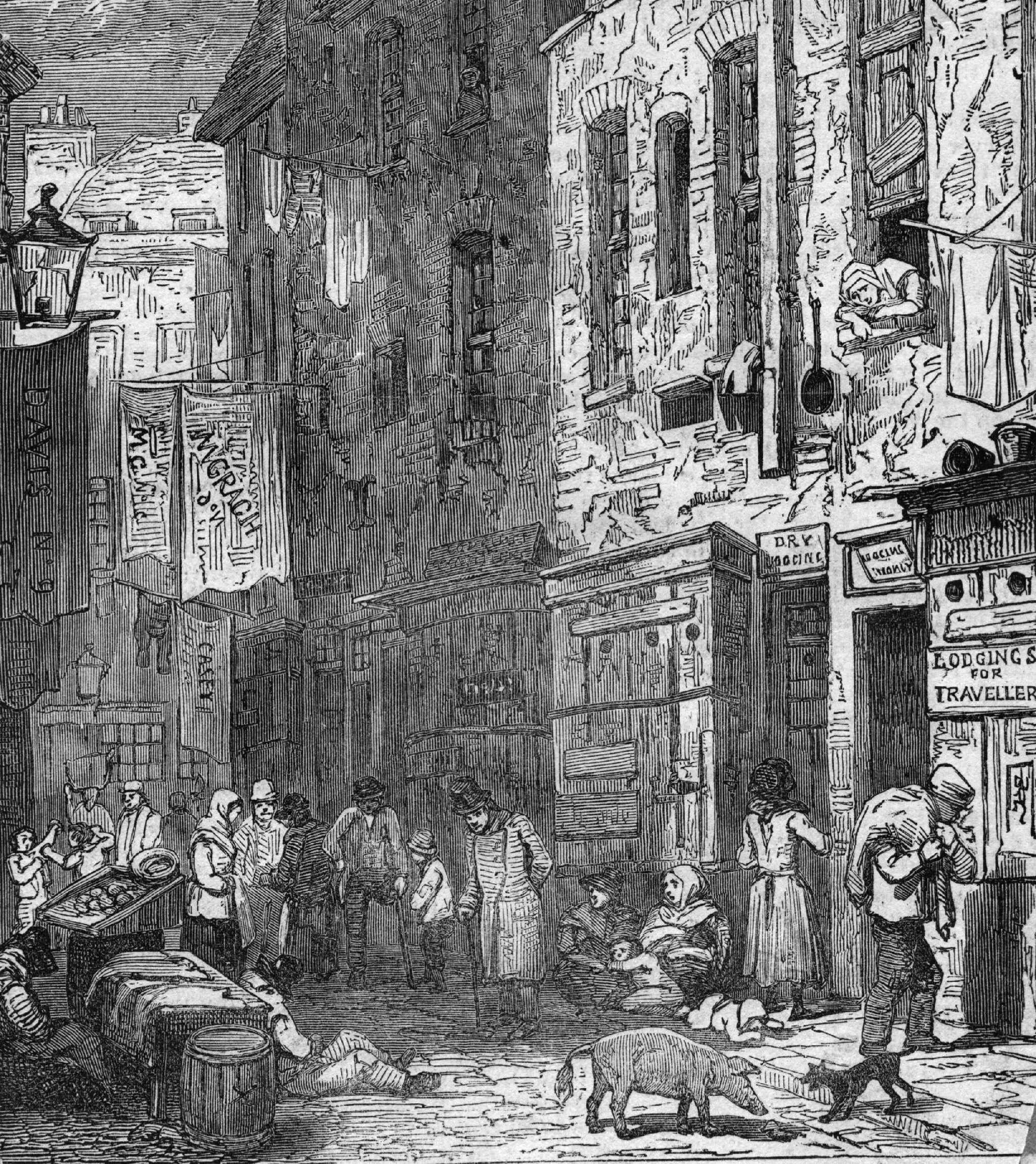

The Infidel Stain takes us to the slums of London in 1841. A printer has been slaughtered, and despite a very similar murder nearby, the police are not interested. Hired by the philanthropic Lord Allington, Blake and Avery are reunited after a long interval apart in which their Indian adventure (The Strangler Vine) has, to mutual embarrassment, become the stuff of national legend. Avery has enjoyed a successful career in the Army, and is the toast of the Oriental Club; the brilliant, truculent Blake still dresses and lives like a poor man. He knows the slums and miseries of the East End from personal experience, and one of the incidental but delightful surprises is that he is related to the poet William Blake, whose lines on London’s “chartered streets” are appropriate to the plot. Henry Mayhew, Dickens and other literary luminaries of the day also play their part. Like C J Sansom’s Tudor mysteries, Carter gives us historical fiction which works on multiple levels, illuminating while entertaining.

The contrasts between the lives of the haves and have-nots in mid-Victorian England echo those of contemporary life. Carter, married to the financial writer John Lanchester, is well-placed to suggest how the country has become “two nations, between whom there is less and less intercourse and no sympathy”, even if the miseries of filth, corruption, prostitution and degradation first recounted in Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor are thankfully beyond what we have today.

Naturally, Blake and Avery have very different views on the powerlessness and sufferings of the underclass: our narrator is a better kind of Tory in that his views on suffrage are tempered by compassion, personal courage and a sense of individual responsibility; the low-born Blake is sharper and angrier at detecting unconscionable oppression by the privileged. The Peterloo Massacre (which Avery has believed to be the “rioting of a criminal mob”) casts a long shadow; as the previous lives of the printers are revealed, the Establishment reluctance to investigate the murders takes on an increasingly political slant. In the face of cold, privation, threats and danger – as well as a shared enjoyment of foreign food – Avery entertains us with his honesty, prejudices and bewilderment at Blake’s intuitions.

The comedy and sincerity of the men’s friendship is done with even more assurance than in The Strangler Vine, which occasionally became bogged down in the complexities of imperial India: the London setting works perfectly. If this series is not bought for film, it would be another mark of the corporate stupidity that lost the BBC Ripper Street. It is, however, far more pleasurable and impressive to read.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks