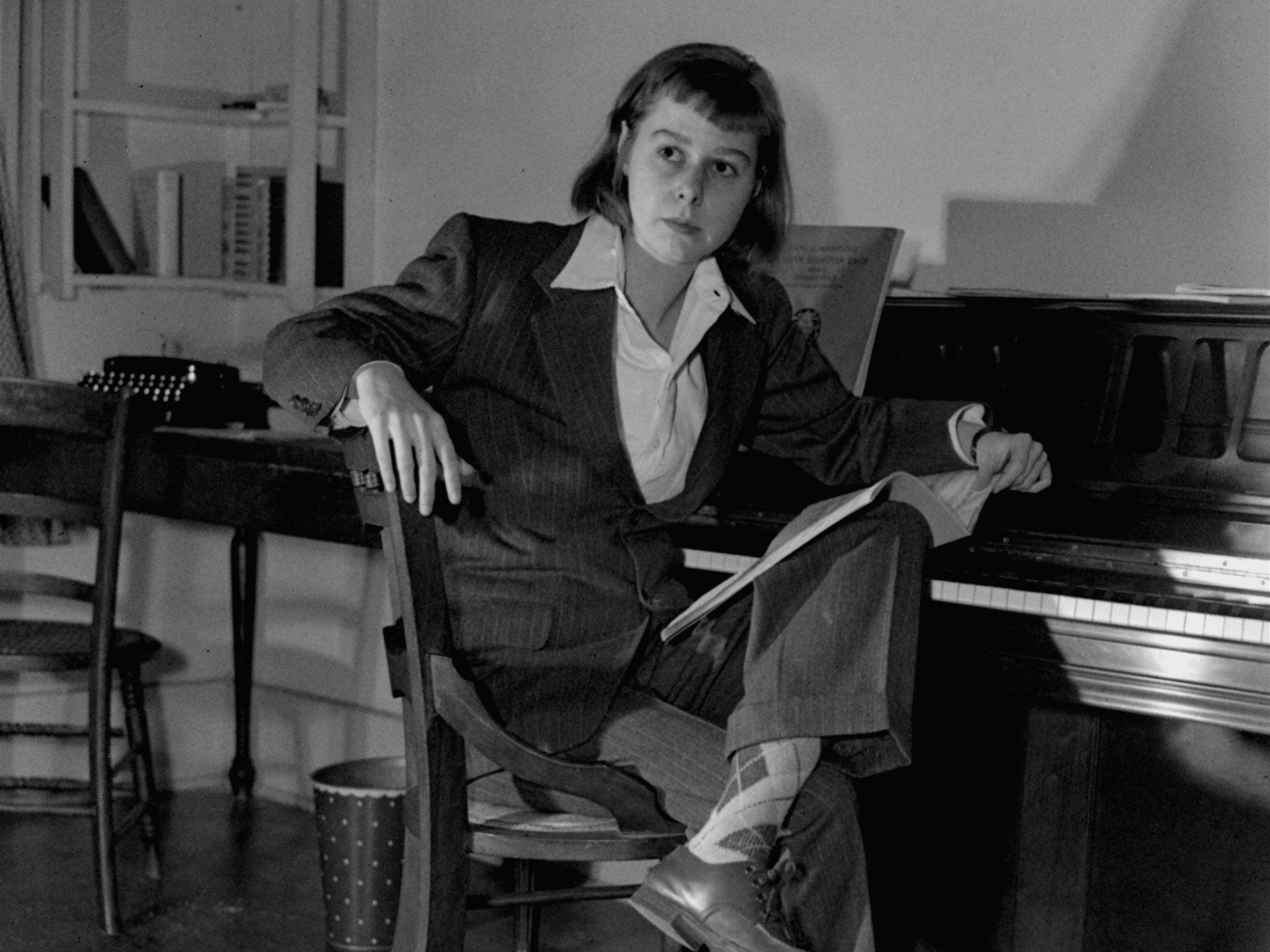

The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers, book of a lifetime

McCullers's book is a model of how to handle the demands of perspective

The idea for The Member of the Wedding surfaced in Carson McCullers's mind as she was running after a fire engine in Brooklyn Heights in 1940, or so the story goes. For months, she had been working exasperatedly on a dead-end version, and it was only when she was interrupted by the squalling sirens and went chasing after them that the book's premise became clear to her. It seems incredible that such a perfectly constructed work could begin in such an accidental way, but somehow it did.

The Member of the Wedding is a short novel with extraordinary resonance. It portrays the defining summer in the life of Frankie Addams, a gangly adolescent girl on the precipice of adulthood who feels so adrift from her smalltown life in Georgia that she becomes unreasonably fixated on the forthcoming wedding of her brother, believing it to be her best chance to escape, and to belong. It is in McCullers's evocation of the tiny desperations of childhood that the novel is most affecting. Frankie yearns to be accepted – as an adult, as a fully fledged member of society – but signs of her naivety are always looming (often darkly) in the narration: "She could not leave until it ended. The soldier was waiting at the foot of the stairs and, unable to refuse, she followed after him. They went up two flights, and then along a narrow hall that smelled of wee-wee and linoleum".

The novel adopts a third person limited point of view that is so well controlled, so richly infused with Frankie's implied language ("At last the summer was like a green sick dream, or a silent crazy jungle under glass") that the reader feels agonisingly connected to her consciousness. It is a model, for any developing author, of how to handle the demands of perspective, and I discovered it at just the right time, when I was working on my first novel and struggling to construct the worldview of my central character, a young man called Oscar Lowe, who felt similar to Frankie in his longing for acceptance and significance.

Sometimes a great book can function like a fire engine siren, too. It can steal your attention, refocus your mind, and lead you to a realisation you would never have arrived at otherwise.

Benjamin Wood's new novel is 'The Ecliptic' (Scribner)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments