The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy review: Her narrative rattles along at the breakneck pace of a gripping thriller

After losing her baby, the journalist's honest and touching memoir, in which tragedy and other problems struck at the heart of her perfect life, is about life not always giving us what we want

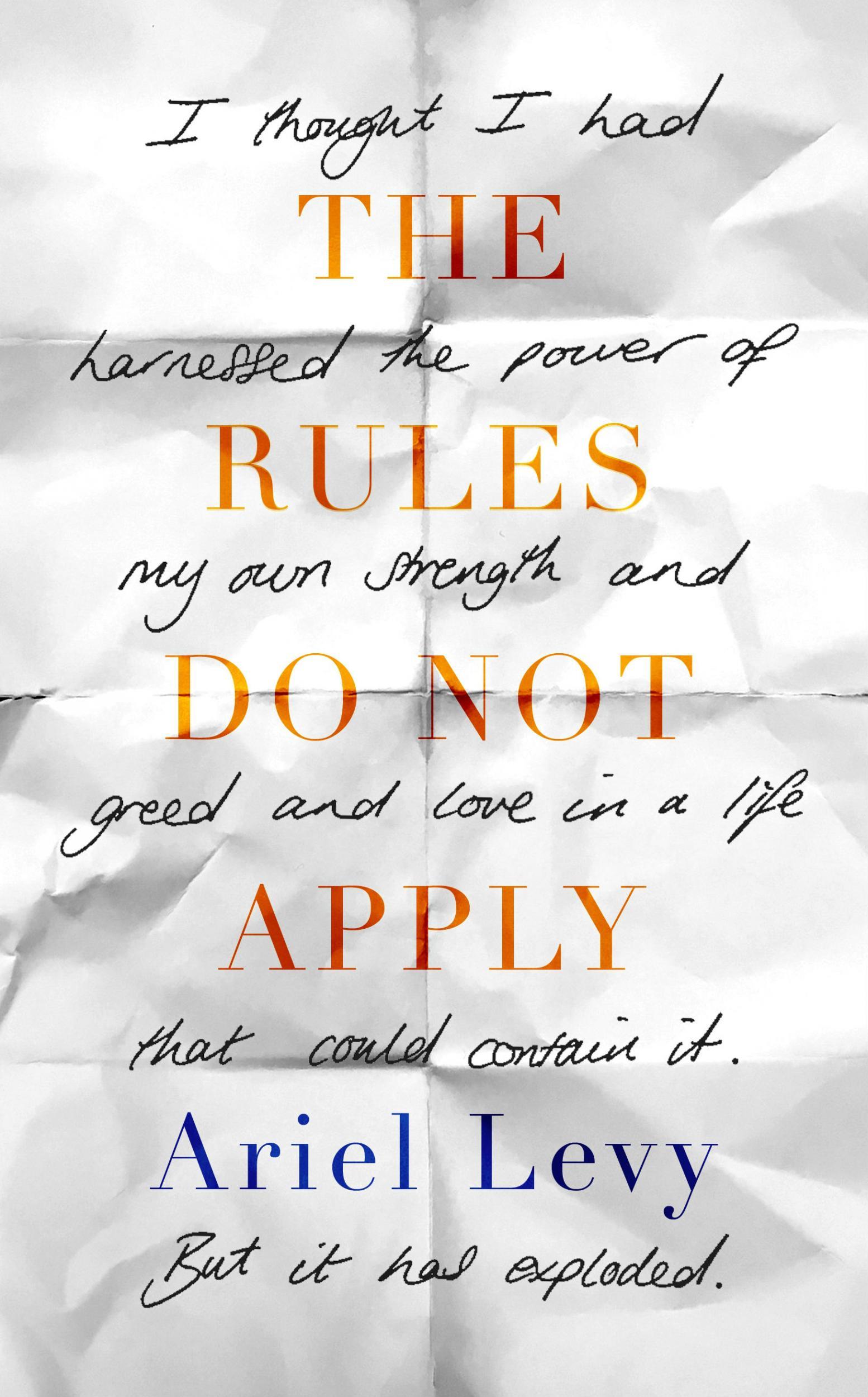

Readers of the New Yorker might recall Ariel Levy’s 2013 award-winning first-person article, ‘Thanksgiving in Mongolia’. Travelling for a story when five months pregnant, she gave birth to her son alone on the floor of her hotel room, shortly after which, he died. What we learn in her candid and moving memoir The Rules Do Not Apply, however, is that this traumatic tragedy nestled at the centre of an all-encompassing implosion of Levy’s so-called ‘perfect life’.

I’m not using this term sarcastically; central to Levy’s account is her realisation that despite our best efforts, life doesn’t always give us what we want. “I wanted what we all want: everything,” she shamelessly admits. “Women of my generation were given the lavish gift of our own agency by feminism—a belief that we could decide for ourselves how we would live, what would become of us.” Levy fully embraced her potential and ambition. As a staff writer at the New Yorker (a job she earned after years of scutwork and learning her craft at New York magazine), happily married to Lucy, the woman she loved (a grand romance of an affair that turned into a life of domestic bliss together), and finally pregnant with their much longed-for baby (the biological father of whom was a supportive friend of independent means and aligning values), she was living the dream. But, even before she lost her baby, if you looked closely enough—which she didn’t, of course: “There were shadows I saw out of the corner of my eye that looked like problems waiting to become real, but you never know with shadows”—cracks had already appeared; namely Levy’s infidelity, and Lucy’s alcoholism.

Her narrative rattles along at the breakneck pace of a gripping thriller, yet her writing is never anything short of crystal clear. She’s particularly good at describing love and loss, two sides of the same coin: the heady, delusional heights versus the plunging, dark depths. “Grief is another world,” she writes. “Like the carnal world, it is one where reason doesn’t work.” Elevating her story from run-of-the-mill misery memoir, Levy’s command of her material is impressive—and again, I choose this word wisely, since the very same training that’s equipped her to be a brilliant memoirist, left her ill prepared for the stumbling blocks strewn in her path. “Writers may be particularly susceptible to this outlook,” she explains immediately after describing how she embraced the “gift” of her own agency, “because we are accustomed to the power of authorship. (Even if you write nonfiction, you still control how the story unfolds.) Life was complying with my story.” In short, Levy thought she could have it all. How naïve, I hear some of you say, and yes, with hindsight, perhaps; but she realises this now, and she’s not afraid to admit that empowerment and guilelessness went hand-in-hand for too long: “Daring to think that the rules do not apply is the mark of a visionary. It’s also a symptom of narcissism.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks