Victorian fairytales and folklore: round up

Fairytales and folklore are cut from the same cloth, but while the former enters the acknowledged literary realm of written text, the latter remains for the most part in the oral tradition, passed down from generation to generation.

As such, Robert Means Lawrence’s The Magic of the Horseshoe: A Collection of Folklore, Myths and Superstitions (Hesperus, £9.99) is an informative beast. His Victorian compendium has been repackaged for the modern day, but the text remains the same as when it was first published in 1899. From the presumed supernatural qualities of the horseshoe as a preventative against bad luck and associated amulets in the shape of horns; the folklore surrounding common salt; superstitions relating to animals and numbers; to the origins of salutations after sneezing, this book covers them all, from the myths of the Ancient Egyptians to the natives of the Fiji Islands. Read between the lines, however, and we perhaps learn most about his initial Victorian readers, eager to uncover the origins of the folklore they lived by.

The Victorians were also fascinated by fairylands, explains editor Michael Newton in his introduction to Victorian Fairy Tales (OUP, £16.99), thus this era saw some of the best fairy tales ever written – fourteen of which Newton has chosen for inclusion in this edition, from familiar names such as George Macdonald, Oscar Wilde, and John Ruskin; to lesser known works like Ford Madox Ford’s ‘The Queen Who Flew’, something of a far cry from his adult novels The Good Soldier and the Parade’s End series. But rather than regard these works as childish entertainment, all whimsy and escapism, Newton passionately argues that these stories offered their authors and readers, “a way to expose social tensions and psychological conflicts and to devise potential solutions.” The inclusion of Dinah Mulock Craik’s ‘The Little Lame Prince and his Travelling Cloak’, for example, highlights Victorian gender inequality. Her protagonist may be male, but critical consensus holds that he represents the female situation. “Fantasy,” Newton explains, “offers the possibility of fantasizing gender relations, both exposing injustice in the real world and opening up the possibility of other social models.”

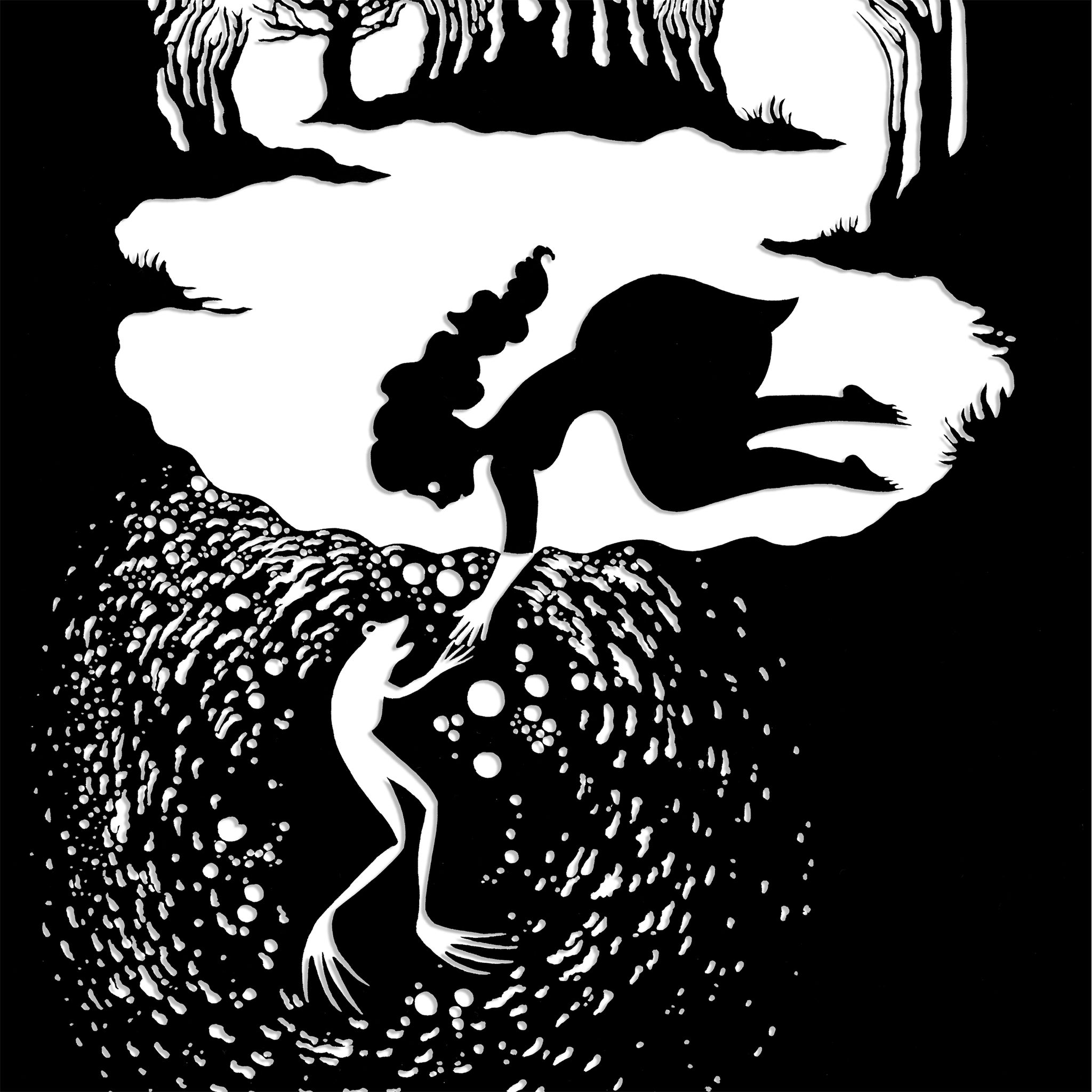

They aren’t, however, all projection and metaphor. An interest in fairies goes hand in hand with the obsession with spiritualism that marked the latter years of Victoria’s reign. Conan Doyle, for example, used the famous Cottingley Fairies photographs as conclusive evidence of “the existence of a spiritual realm.” But rather than see this as a rejection of or a reaction against the logic of science, if we turn to Melanie Keene’s Science in Wonderland: The Scientific Fairy Tales of Victorian Britain (OUP, £16.99), she presents us with a compelling argument for “the close relationship between fact and fancy”. Although just out of the Victorian age proper, what with the crossover of magic, the science of photography, and the dark recesses of parapsychology, I felt the case of the Cottingley Fairies haunting Keene’s text. From the identification between dragons of myth with newly-discovered dinosaur fossils; the links between the study of entomology, “an increasingly popular participatory science” of the period, and the “conventions of giving fairies butterfly-like wings, cricket-like voices, and a mayfly existence”; to the evolutionary theory enfolded in Charles Kingsley’s nursery classic, The Water Babies, Keene provides a wealth of examples of magical creatures as metaphors for the scientific developments of the Victorian age. The illustrations are rather brilliant too – a water molecule portrayed as a trio of fairies holding hands – the book is marred only by her often overly convoluted style, which sometimes makes for confused reading.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks