Wilde in America: Oscar Wilde and the Invention of Modern Celebrity by David M Friedman, book review

The dramatist toured the US in 1882 and blazed a trail for all celebrities to come

Perhaps it is merely romantic to suggest that the stylised wigs, satin breeches and silver-buckled shoes worn by our bishops, peers of the realm and high court judges have a homoerotic component.

The gorgeous faux ermine stoles worn in the House of Lords are offset by crimson robes with silk ribbon ties and tassels. Englishmen of a certain sort embrace drag. Mick Jagger, the Danny La Rue of rock, fetchingly impersonated a woman on the cover of the 1978 Stones album Some Girls.

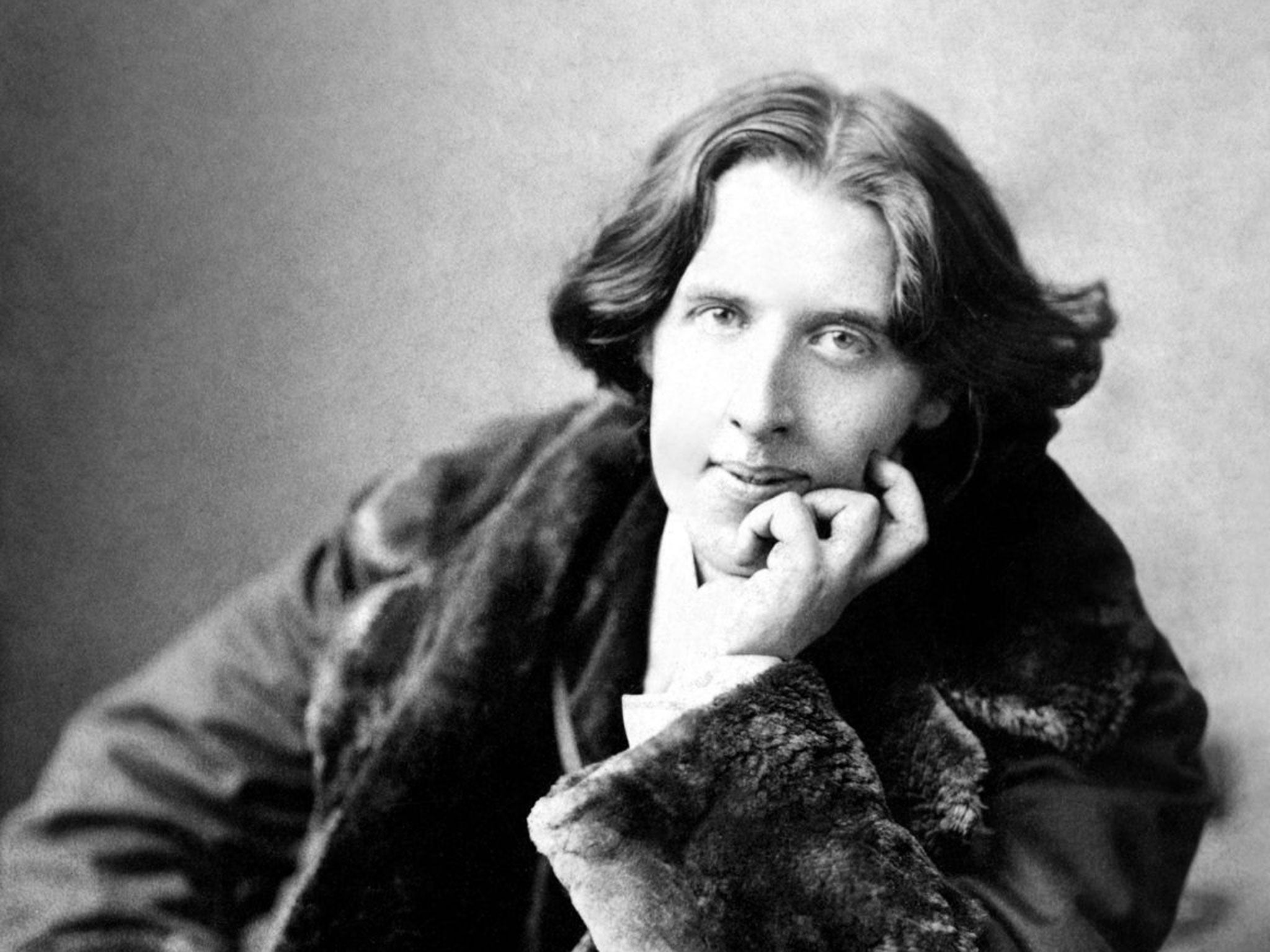

Oscar Wilde, the queen of sartorial finery, toured America in 1882 in a velvet coat with lace trim and a trunkful of blouses with low-cut Byronic collars. "If I were alone on a desert island and had my things", the 27-year-old Dublin-born aesthete declared, "I would dress for dinner every night." With his plucked eyebrows, applications of rouge and his nails carefully manicured, Wilde presented a celebrity-conscious image of style and self-adornment. His plan in 1882 was to bring the British aesthetic movement to America and cauterise the nation of its vulgar (as he saw it) materialism.

However, when Wilde stepped off the boat at New York on January 3, he had yet to write any of the works that would earn him fame. The Importance of Being Earnest, The Picture of Dorian Gray, De Profundis and The Ballad of Reading Gaol were all some way off. Through his self-promotion and gift for turning himself into a commodity, though, Wilde became famous in America merely for being famous. Without his genius for self-promotion, conceivably, there might never have been an Andy Warhol or, indeed, a Jade Goody. Such was the importance of being Wilde.

In his impeccably-researched and absorbing chronicle, Wilde in America, the cultural historian David M Friedman argues that Oscar Wilde was responsible for creating what we now call "celebrity culture". In the course of his ten-month tour of America the self-adoring dandy gave 150 lectures on aesthetics and interior decoration, generated more than 500 newspaper and magazine articles, and consorted with society belles, prostitutes, industrialists, journalists and even penitentiary inmates. ("Oh dear, who would have thought of finding Dante here?", Wilde marvelled on finding a copy of The Divine Comedy in a Nebraskan jail.)

From Canada to the Gulf of Mexico it was an extraordinary journey as Wilde travelled 30 states. Wherever he went, he was overwhelmed by crowds and applause. If there were any misunderstandings, it was because the giant, 6 ft-3 Irishman represented an unfamiliar figure on the American scene. Even when addressing workers in a Colorado silver mine, the self-styled "Professor of Aestheticism" wore a dyed green carnation in his buttonhole.

Not all Americans warmed to this extraordinary creature. The Civil War veteran and journalist Ambrose Bierce sniped: "There was never an imposter so hateful, a blockhead so stupid, a crank so variously and offensively daft." On the whole, however, Wilde was generally liked. According to Friedman, Wilde's immense reputation stemmed from his American trip. The Picture of Dorian Gray, his great 1890 novel, was commissioned by the American editor of Lippincott's magazine, JM Stoddart, who had introduced Wilde to the fellow homosexual poet Walt Whitman. Wilde's mission to bring swags of lilies and tales of the Italian Renaissance to the American people met with Whitman's unqualified enthusiasm.

Witticisms flew like confetti. In Washington a woman approached Wilde and said: "So this is Oscar Wilde: but where is your lily?", to which Wilde replied: "At home, madam, where you left your good manners." He became an unforgettable name in America. But of course the honeymoon did not last. In 1895, 13 years later, he was tried in London for "gross indecency" (Victorian-era code for homosexuality) and afterwards jailed. The image-conscious aesthete had been consumed by the monster of his own celebrity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks