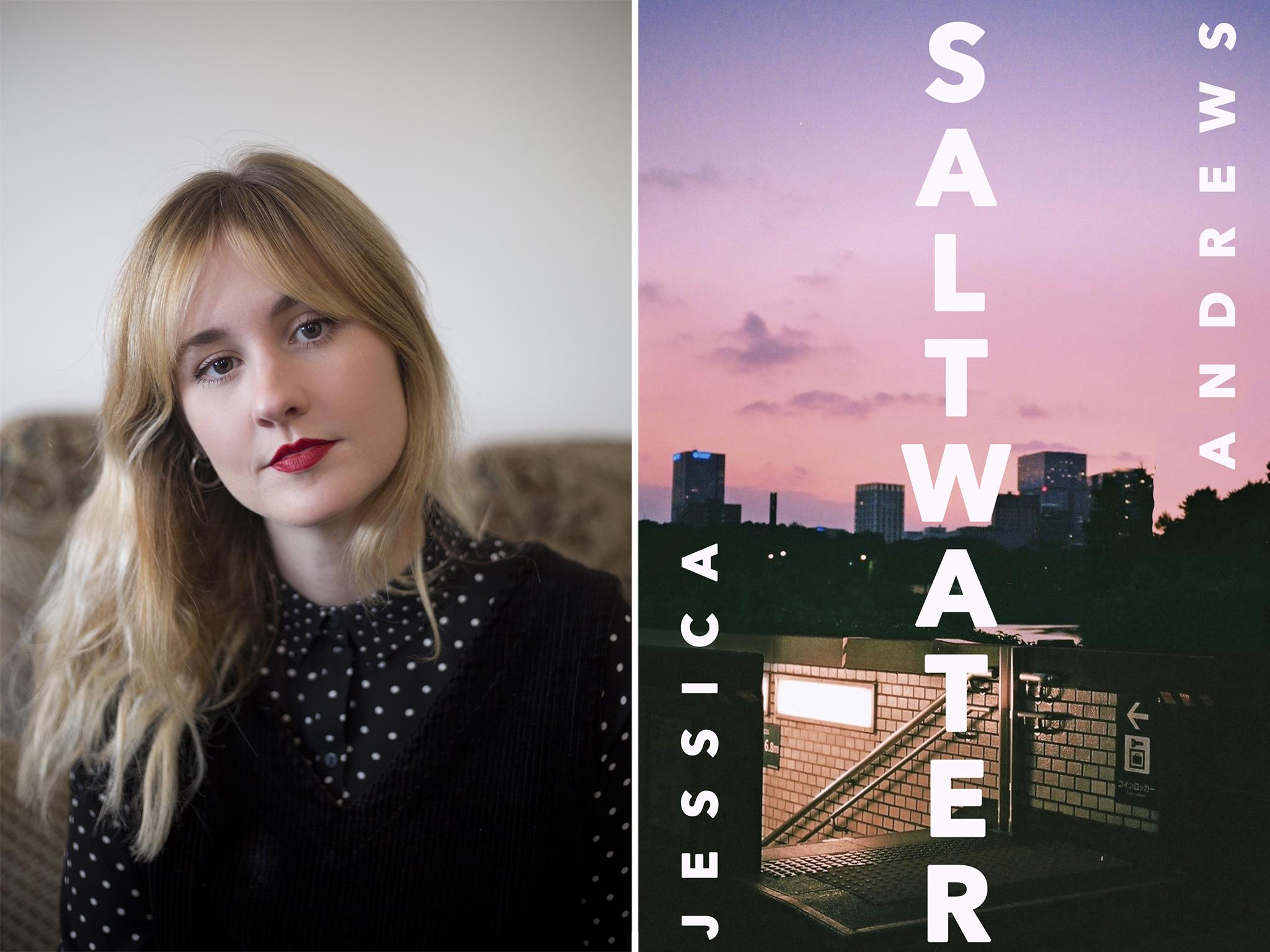

Book review: Saltwater by Jessica Andrews: Debut novel shimmering with promise

A distinctive new voice for fans of ‘Fleabag’ or Sally Rooney, this autobiographical work about a young woman figuring out her place in the world will surely find readers who’ll groan and declare they ‘feel so seen’

Jessica Andrews’ debut novel shimmers with promise: it’s one of those books where, from the first pages, you’re grabbed by a distinctive new voice.

Andrews has a real talent for description, which elevates this autobiographical work from slightly unearned naval-gazing memoir – she is in her mid-twenties – to something more memorably textured.

But it can also be too much, the vivid spray-painting of tiny detail ultimately obscuring any bigger picture. As Andrews churns through the years, glittering descriptions mount up but meaning or narrative drive doesn’t.

Saltwater is about figuring out who you are, on your own, while acknowledging your place in the line of those who went before you. It’s formed of short, bite-sized chapters that flicker between the present – Andrews’ narrator Lucy has inherited her grandfather’s cottage in Ireland, and fled there from her chaotic London life – and memories of her working-class family and upbringing in Sunderland, as well as more poetic sections on her bodily bond with her mum. These viscerally explore mutual dependency, and provide a counterpoint to the rest of the book’s narrow focus – Saltwater will do nothing to dissuade those who think millennials are too self-absorbed, I’m afraid.

(Side note: the novel feels like it’s been marketed slightly cynically as a broke and broken young-woman-in-the-big-city story, for fans of Fleabag, or Irish author Sally Rooney. This is only a small part of the narrative – just more floggable than Noughties Sunderland, presumably.)

Lucy’s shifting closeness with her mother – not to mention thornier relationships with her alcoholic father and deaf brother, strangely underwritten – pull the book into its most interesting territory. But too often Saltwater is just about Lucy’s inner anxieties, and the changing external trends of the world she’s growing up in. This can leave the novel seeming, at times, more a pretty sketch of ennui in a vintage frock than anything very profound.

Andrews is very good on subtle gradations of class, however, especially as Lucy moves from Sunderland to London – and she’s even better on the general youthful yearning for our lives to begin, to become some other, ill-defined, more exciting thing. Also impressive is how the disappointment at not finding that, at not fitting in, is often rendered in bodily terms: Andrews smartly elides the notion of feeling uncomfortable in our own skin with the idea of not having found our place or purpose in the world.

It is all very relatable, especially if you’re roughly of her generation. I felt pinprick-precise needlings of nostalgia; Saltwater will surely find readers who’ll groan and declare they “feel so seen”. But if some of the period detail may give you flashbacks (a line about copying Jacqueline Wilson illustrations into a fluffy notebook certainly catapulted me), Andrews leans rather too heavily on her litanies of it. Teenage years are measured out in Tia Maria-and-orange and MSN messenger, student days delineated by vodka and tote bags, warehouses and mephedrone. I stopped counting sweet brands after fizzy cola bottles, Wham bars, Drumstick lollies, Parma Violets and Opal Fruits piled up within 10 pages.

Much of Andrews’ imagery is persuasive. It’s often raw, unsettling: unspoken thoughts get trapped under skin “like blisters”; overflowing bath water “dripped guiltily” through floorboards; spilled candlewax “hardens into a long white scar”. But it can be overwritten. It’s almost as if she’s effortfully ticking off the five senses: next to that gorgeous wax image is the more dubious “the sunsets are crisp and smell of cardigans”.

Her form suits her story, each short chapter a memory-fragment, flitted through rapidly. The rhythm allows Andrews to evoke the sensory overload of her protagonist’s buzzing, overstimulated mind. On a craft level, it feels like a wee bit of cheat, mind – tight, clever vignettes drawn from your own life are easier to hone and arrange than conventional narratives are to sustain. But perhaps I am not being generous, given this is a debut – and given that each vignette is so sharply cut, with such high shine. Saltwater shimmers with promise, and it will certainly be worth watching what Andrews does next.

Saltwater by Jessica Andrews is published by Sceptre on 16 May, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks