David Bowie’s Lodger finds a new home: Philip Glass and John Adams discuss tribute symphony

On the anniversary of Bowie’s death, Philip Glass premieres a new work inspired by the pop icon's 1979 album, conducted by John Adams. Zachary Woolfe talks to the two composers

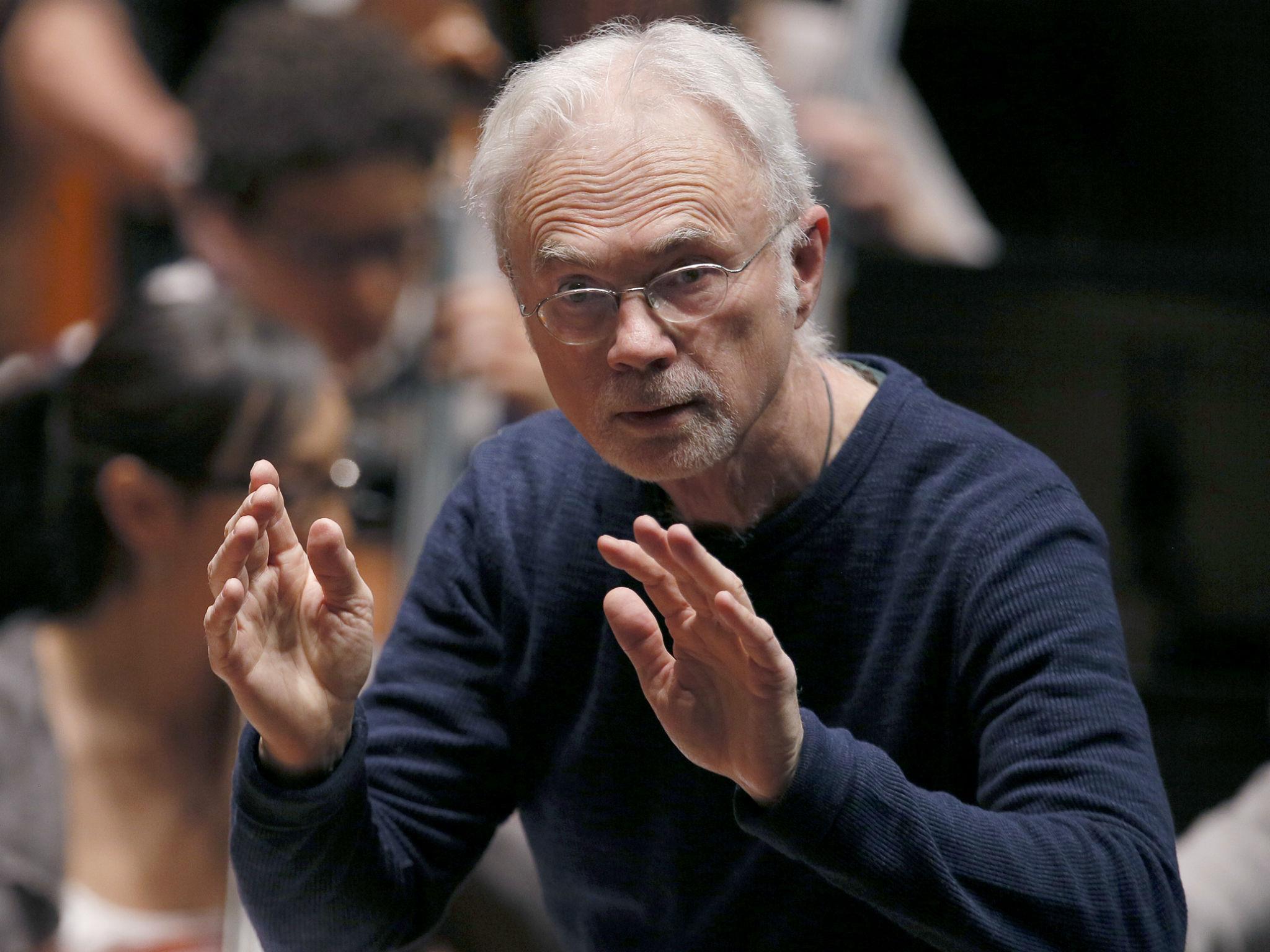

Three years to the day after the death of David Bowie, two eminences of American music will come together in Los Angeles to pay tribute. John Adams is set to conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the premiere of Philip Glass’s Symphony No 12, Lodger, at Walt Disney Concert Hall on Thursday. In May, the symphony will have its European premiere at London’s Royal Festival Hall.

The work is inspired by Bowie’s 1979 collaboration with Brian Eno and the producer Tony Visconti, the final album in what’s usually called their Berlin trilogy, which also includes Low and Heroes, both from 1977. Glass’s First Symphony, back in 1992, was based on Low; his Fourth (1996), on Heroes.

“I put off the third for a long time – 20 years – before I realised that I owed them something,” Glass said in a recent telephone interview.

Adams was also on the conference call – he in Berkeley, California, Glass in New York to discuss the symphony, Bowie and whether Glass’s music is hard to conduct. Here are edited excerpts from the conversation.

How did this symphony come about?

Philip Glass: It’s part of a commitment I had made to David Bowie and Brian Eno to take three of their records and turn them into symphonies. In Lodger, to me the most interesting thing was the lyrics, the poems.

In the earlier ones, the musical idea was quite challenging and worthwhile to work on, but when I got to Lodger, I didn’t find that interest in the musical part of it; the interest was in the text. After hedging a little bit, I thought I might as well make a song symphony. Mahler, of course, was the great one at that. I used seven of the texts; I didn’t use all 10. That would have pushed me over an hour, and I didn’t want to go there.

I don’t know, John, if you’re aware of this, but this was written – the words were written – when David was living in Berlin.

John Adams: Yeah, you mentioned that to me.

Glass: And Brian was there, and Iggy Pop was there; those were his companions. They were there trying to make a movie out of The Idiot by Dostoyevsky. None of them spoke Russian, or German, even. But on the other hand, these were three really interesting people in our music world and music life, and made big statements – icons, all of them.

Adams: A really great text is just so generative; it produces the best music. If I have a concern about some operas these days, it’s that the texts are just not good enough. It doesn’t have to be someone with a deep literary background; it can be a David Bowie or Brian Eno. The great thing about American music is the total bleed-through of, if you want to call it that, high or low, popular versus art. I think both Philip and I share this. We have very loose filters in terms of classification.

When did you first hear each other’s music?

Adams: The thing I remember most vividly is a tour of the ensemble doing excerpts from Einstein on the Beach, which I heard in San Francisco sometime in the 1970s. Then I actually conducted quite a bit of his music — a little piece, Facades, and then I think we did the very first performance of parts of Akhnaten in LA on a Philharmonic program. I did the Ninth Symphony, again with LA, and then this.

I came of age during what we now call the bad old days, when the world said you had a choice between European modernism and its American version, or Cagean aesthetics. Hearing Philip’s music and Steve Reich’s music was this wonderful, new possibility of a language that embraced both tonality and sort of living with a pulse, new, original and fresh.

Glass: I was very much taken with hearing John’s work – of course, Nixon in China we talked about a number of times. It’s not enough to create a style of music or identity of your own; what you really want to be is in the company of other people. It’s more meaningful to be part of a large group of people sharing ideas.

He was the first time I met someone who wasn’t part of my immediate generation but had the interest and talent. How many operas do you have now? Five or six?

Adams: Not as many as you do! [Depending on how you count, Glass has composed nearly 30.]

Is Philip’s music tough to conduct?

Adams: It continues to be a slow absorption of Philip’s orchestral music into the regular repertoire; I’m surprised that more conductors haven’t taken it on. He has a couple of symphonies, like the Eighth, where there are some real challenges rhythmically.

But it’s not hard to conduct on a technical level. I think the challenge is creating a sound, and with some orchestras it’s simply getting them into the right frame of mind. Something like the Ninth Symphony, which is nearly an hour long, it demands a kind of Zen-like concentration by the players, the way some Bruckner symphonies do. It’s not like doing The Rite of Spring, where there’s a thrill every 10 seconds. You have a steady build and a long line.

What does it pair best with?

Adams: I don’t think there’s a great challenge there. You could put anything with it. I see programmes that have put a piece of Philip’s together with a Baroque piece; that makes sense in certain ways. I’ve put his smaller pieces on programmes with my own music, but sometimes with Steve Reich or Terry Riley: obvious harmonious conjunctions. This program we’re doing at the LA Phil, I’m doing with an old piece of mine, Grand Pianola Music.

Glass: I’m delighted to be able to hear it again. I haven’t heard it in a long time.

Philip, does it annoy you that these symphonies are still not done more widely?

Glass: Quite the opposite: I’m astonished at the size of audiences I’m getting now. I never thought that this music would be accepted in the way it’s being accepted. I had my first performance with the New York Philharmonic when I was 80 years old. I mean, come on!

I think it’s partly that I’ve been helped by a younger generation that has very broad ideas and taste, and I don’t seem nearly as strange as I used to be. I’ve become – not mainstream, that seems a little too far – but still I can tell from the Ascap (the music licensing agency) reports that the music is being used.

Adams: A central thing about Philip’s music is it is utterly original, it is immediately identifiable as his, and that is an extraordinary thing, and it’s actually a very rare thing. It’s such an astonishing thing that Philip did, which was to take very, very simple materials and a simple mode of expression, and create something that was original. And it just caught on in an immensely popular way. It’s an honour to be a part of it.

Glass: I have to publicly apologise for getting you the score so late.

Adams: It’s OK; we all do it.

Symphony No 12 (Lodger) will be performed as part of Philip Glass: The Bowie symphonies by the London Contemporary Orchestra, conducted by Robert Ames, at the Royal Festival Hall, 9 May (southbankcentre.co.uk)

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks