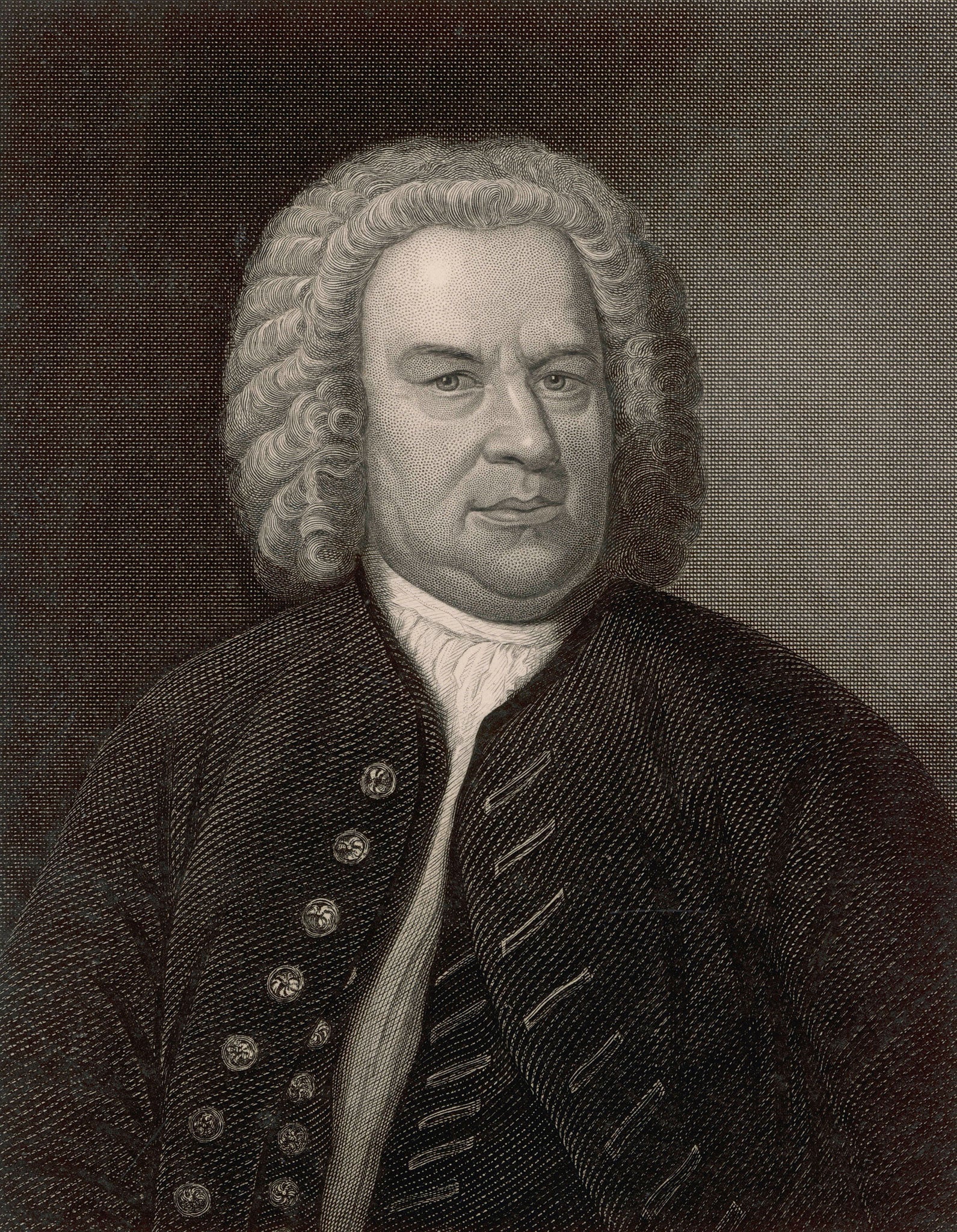

Johann Sebastian Bach: Leading soloists on the mastery and mystery of the genius composer

There's a composer whose genius is so unfathomable that he pushes musicians to the very brink. Leading soloists talk to Boyd Tonkin about capturing the spirit – and solving the puzzle – of Johann Sebastian Bach

In 1977, Nasa's two Voyager space probes began an endless mission across the Milky Way that has already sent Voyager One beyond the borders of our solar system and out into the interstellar void. Before they launched, the astronomer Carl Sagan invited proposals for the content of the "golden records" aboard each craft, designed to inform curious aliens about life on Earth. Biologist Lewis Thomas suggested the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach, but then had second thoughts: "That would just be boasting."

All the same, the long-serving Cantor of the Thomaskirche in Leipzig does now glide towards the stars. He is represented on the discs with not only a Brandenburg Concerto but two solo instrumental works: a violin partita played by Arthur Grumiaux, and one of the 48 Preludes and Fugues from the two books of The Well-Tempered Clavier. The latter comes in a piano version by the wayward Canadian genius Glenn Gould. As I write, these sonic wanderers are precisely 19,618,915,209 kilometres from home.

When and if some life-supporting planet in the constellation of Camelopardalis hears the Gould, its inhabitants need to know that, back on our blue marble, music-lovers are still arguing about him. He's too fast, too clinical, too jazzy, too percussive, he sings along too much… and so on.

Equally, they ought to understand that, for millions of earthlings, this music has gone back to its rightful home: it belongs to the heavens. Take two minutes to listen to (say) the opening C major Prelude of The Well-Tempered Clavier, and the idea that Bach might have composed the call sign for Planet Earth sounds far from outlandish.

When Pablo Casals, whose late-1930s recordings of Bach's Cello Suites became an aural icon of humanism and peace against fascism and war, was asked to pick one piece of music for the whole world to hear, he chose the sarabande from the fifth suite in C minor. Yo-Yo Ma played this movement in Manhattan for the ceremony, in September 2002, to commemorate the first anniversary of 9/11. The Russian master and Soviet dissident Mstislav Rostropovich brought the Cello Suites to Checkpoint Charlie as the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989. Ma himself played the same music to say farewell to his friend Steve Jobs – a Bach aficionado – at the memorial service for the Apple co-founder.

Somehow, these fiercely learned works that began as virtuosic exercises or even teaching aids now enshrine an ecumenical ideal of sacredness. In a brilliant early-1960s talk for Canadian TV, Gould said that all music since Bach's time had lost "that inordinate state of ecstasy that Sebastian Bach never thought to question". Gould would find it apt that his Well-Tempered Clavier piece now shoots towards infinity: "For Bach, it wasn't finality that mattered in music, not really; it was simply the joyous essence of being."

Bach's solo works speak to modern players and listeners as a sort of gold standard, or even holy grail – precious scriptures where unique insight and revelation lie. The tradition goes back to Beethoven, who called The Well-Tempered Clavier his "Bible".

This is a strange paradox. These instrumental sets and suites for violin, keyboard, organ and cello often look so technical, so formal, as they tease out every harmonic strand within the musical DNA of a slender phrase or theme. So how can they cast such a spell in contemporary ears? The chastely gorgeous The Art of Fugue, which Bach left unfinished at his death in 1750, doesn't even specify an instrument. Its dozens of arrangements for both soloists and ensembles include one for a saxophone quartet.

Yet the distinguished Bach interpreter Angela Hewitt – like Gould, a Canadian piano virtuoso, though of a far less extraterrestrial stamp – tells me that "in its austerity, it has such beauty of expression." She sees in it "one masterpiece after another. It's mind-boggling when you play it." The British pianist Joanna MacGregor loves The Art of Fugue but notes that "a lot of people argue that it's not meant for performance at all – that it's a set of exercises or a philosophical investigation". Hewitt considers it the work of an ageing master "pushing himself ever more forward, even though his style was already seen as out of date". MacGregor meanwhile treats it as "a rock-face": epic, challenging, but with an awesome view. Still, she recalls that, when she discussed it with the composer Harrison Birtwistle, he had a brisker reaction: "That Bach – he's such a show-off."

These works, though, manage to move as much as they awe. Hewitt asks: "Why in particular do the Goldberg Variations have the emotional effect that they do? Why is it akin to a spiritual experience, even when there's nothing sacred in it?" In 1955, it was Gould's best-selling Goldbergs LP – a bebop-like blizzard of breakneck virtuosity – that helped place solo Bach at the heart of Mad Men-era "cool". Hewitt suggests that, as its exquisite aria voyages like a spacecraft through 30 incarnations in distant harmonic galaxies and then touches down, "it's a long journey that leads back to the beginning: a homecoming, and we like to feel that. But it's a mystery how he does it."

At this year's BBC Proms, audiences will have several opportunities to plumb the mysteries of unaccompanied Bach. In a series of late-night concerts, his works "senza basso" – without even a basso continuo to partner the exposed instrument – will take pride of place. Edward Blakeman, the director of the BBC Proms 2015, says that the nocturnal Bach gigs "will be very intimate, in semi-darkness with a single spotlight focused on the stage. A lone performer can draw you in and you feel part of a unique, shared experience."

Sir Andras Schiff will play the Goldberg Variations, Ma the Cello Suites, while the prodigiously talented young Russian-born violinist Alina Ibragimova will take on the six Sonatas and Partitas. Patiently, Ibragimova meets my clumsy efforts to pin down the ineffable appeal of the Bach solo repertoire with a succinct formulation. "For me, it's like it speaks of everything," she says: "And it's always true."

Critics can perch smugly on the mountain-top of Bachian metaphysics. Players have to climb up, ledge by ledge, through sheer hard graft. These works are tough. Above all, one instrument often has to stand in for an entire orchestra, and hint at harmonies that it alone cannot produce. The American violinist Hilary Hahn, who began her recording career with solo Bach, recalls: "At the beginning, I remember trying to figure out, how do I do all this? The string-crossing, the double-stops, the chords. It was so much like patting my head and rubbing my tummy at the same time." For Hahn, "it was really my first experience of polyphonic music, and it's still unusual to come across something so polyphonic." She finds Bach's violin writing so densely interwoven that "if you change a little detail on the spur of the moment" in performance, "it changes everything. You have to work that out over the rest of the page or the movement. It's always fresh, and I'm always on my toes".

Ibragimova remembers that "it was quite a struggle to begin with, to really accomplish what's there in the music. You need to be very technically assured." Any performer of the solo works faces the challenge "of letting the whole seriousness of Bach show, and at the same time of feeling every emotional phrase". The master gives few clues. Bach's autograph manuscripts are things of beauty in themselves, but they offer to performers little guidance in the way of dynamic markings or other hints and steers.

Hence the inexhaustibly wide spectrum of sound and mood that one Bach piece can generate. MacGregor stresses that "one of the hardest things about Bach is that he presents you with a very pure score. So it's an exploratory process." Thus 20 versions of the Goldbergs will reveal 20 different visions. "It can be very liberating; it seems to ask you a lot of questions." Go back to that limpid C major Prelude. To Sir Andras Schiff, it's a rippling stream; to Edwin Fischer (MacGregor's favourite Bach interpreter), virtually a boogie-woogie.

In his tremendous book about Bach, Music in the Castle of Heaven, the conductor John Eliot Gardiner argues that this scary freedom bears traces of Bach's practice as a celebrated improviser at the keyboard. And he finds the violin sonatas "festooned with little time-bombs of harmonic potential" that both performer and audience have to realise. Player and listener are "required to complete the creative act". As Hahn puts it, "You don't always know where you are going. But as a listener, you know that if you put one metaphoric step in front of another, > you will arrive there." She thinks that "there's something about great solo works that allows the audience to make their own interpretation. Something about it zeroes in on one point."

MacGregor says that her involvement in the early-music movement, with its efforts to discover and replicate the sounds of Bach's own time, "gave me confidence in a more improvisatory approach to his ornamentation and decoration". Bach, many players have thought, invites them to take liberties – because he took so many himself. The late-Romantic transcribers who blew up delicate solo suites into "Big Bach" for mighty symphony orchestras certainly did that. And so, inevitably, did some of the many jazz players who took to Bach like syncopated ducks to water.

A few jazz virtuosos sought to make Bach swing even more than he already does. MacGregor recalls that "to me aged, eight or nine, it felt quite jazzy. I loved Dave Brubeck too and, at that stage, I could barely see the difference." Jacques Loussier and his trio built a career on albums that blended improvisation-based cool jazz into Bach and stirred it into the ultimate mid-Sixties cocktail: not so much Mad Men, perhaps, as Austin Powers. Remember the Hamlet cigar ad? That was Loussier. And in another corner of the Sixties, the same theme took up residence in Procul Harum's "A Whiter Shade of Pale". In his ear-opening book Reinventing Bach – about how changes in recording technology have transformed the way we hear this music – Paul Elie explains that pop culture always adored JSB: "Beethoven was rolled over, but Bach was left standing."

Many jazz greats sat down at the keys with a respectful, even reverential, view of Bach. Fats Waller loved the organ works. He played them straight, though his record company, Victor, refused to release these versions. An apocryphal story plants Fats in the organ loft at Notre Dame in Paris in 1932, blasting out a Bach Toccata and Fugue. It probably never happened, but Waller – who told variants of the yarn – clearly wished that it had.

Bill Evans, Miles Davis's pianist and a distinguished composer-performer whom Glenn Gould admired, refused to muck around with Bach. Some Bach buffs, let alone jazz fans, find piano wizard Keith Jarrett's scrupulous versions of the Goldbergs and The Well-Tempered Clavier on the harpsichord a little too polite. "This music doesn't need my help", Jarrett has said. For him, Bach's note "is always better than yours". Besides, even the most radical jazz take on solo Bach can end up as an act of worship. Listen, for example, to the late free-jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman attempting to carpet-bomb the first Cello Suite, as played by Tony Falanga on the double bass, with a cacophonous sonic blitzkrieg delivered on his trumpet and alto sax. Bach wins, as Coleman always knew – and planned – he would.

So delicate, so abstract, this is music built to withstand a nuclear strike. Iranian-American harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani says, "Bach's music can survive a host of orchestrations: they simply shed light on it." Whatever the instrument, "ultimately, I'm hearing Bach's message. Even on the harpsichord, one is in a sense transcribing and interpreting. We're always translating".

Musicians never tire of this repertoire. For Ibragimova, "it's a never-ending journey with Bach," as a listener as well as a player: "When I listen to someone else playing the solo works, it's a real meditation." Esfahani reflects: "All these years I've spent with Bach, and sometimes I don't think that I understand anything. But you can do things in life that you don't understand." Like faith, he suggests, or love: "We're always groping and grabbing" in the dark. Above all, "at the end of the day, you have to play well."

Steven Isserlis would say amen to that. The leading British cellist released an acclaimed recording of the Cello Suites in 2007. Following an eight-year break, this summer he will tour them around the festival circuit. Why the hiatus? "It's not from lack of love; it's from too much love. Just because I haven't been playing them does not mean I haven't been thinking about them." Isserlis sees them as "fascinating and enigmatic" pieces but also – that old Bach conundrum – "very human and communicative" too. Musicians have often hunted for a narrative programme or pattern in Bach's intimate works. Isserlis remains convinced that the Cello Suites represent the life of Christ. For him, they form a set of six devotional "mystery sonatas", three joyful and three sorrowful. However, he insists that players must never let such a reading skew the music: "Ideas and theories are the big enemy." Rather, its innate loveliness can move hearts. "The solo instrument has that purity, that vulnerability, that people love."

Once in fashion, story-telling around Bach's solo works has fallen out of favour. Some autobiographical speculations do survive: the idea, for instance, that the stupendous Chaconne in the second violin Partita – to Yehudi Menuhin, "the greatest structure for solo violin" – serves as an elegy for Bach's first wife, Maria Barbara, who died in 1720.

In truth, the music needs no such props. Last December, I heard the Korean virtuoso Kyung Wha Chung finally conquer her acute nervousness during a UK comeback concert (a decade after a finger injury had forced her off the public stage), with a grandly passionate, unashamedly Romantic rendering of the Chaconne. As ever with unaccompanied Bach, the music in the right hands will tell its own, thoroughly dramatic, story.

However, with Bach it's not always a matter of emotional intensity on one hand, and architectural finesse on the other. For Hewitt, "the spirit of the dance" lies at the root of his sound-world. "That's one of the most important things. Miss that and you miss an awful lot." Isserlis sees the Cello Suites as "dance movements above all". MacGregor quotes Stravinsky: "His music is in the end about dance." Gardiner feels that "the worst interpretative sin… is to plod in Bach." Fats Waller, who came from the dance halls but dreamed of the organ lofts, had his finger truly on Bach's pulse.

MacGregor affirms that Bach has "wit and light and humour, as well as a great capacity to express emotions". Every time, moreover, "you're in conversation – with someone who has an awful lot to say." That, Isserlis admits as he prepares to scale the Himalayan peaks of the Cello Suites again, can be a daunting dialogue: "I don't see how people can resist them. This is the ultimate beauty. There's nothing more beautiful in the world." No pressure, then. "They are so perfect. I have the perfect cello and the perfect bow. So the only thing that can let it down is me."

Upcoming Bach

At the BBC Proms, Alina Ibragimova plays the Sonatas and Partitas on 31 July and 1 August; Sir Andras Schiff the Goldberg Variations on 22 August, and Yo-Yo Ma the Cello Suites on 5 September: bbc.co.uk/proms. Steven Isserlis's recording of the Cello Suites, Alina Ibragimova's of the Sonatas and Partitas, and Angela Hewitt's of the Goldberg Variations, 'The Art of Fugue' and 'The Well-Tempered Clavier' are all available on the Hyperion label. Joanna MacGregor plays the Goldberg Variations on 3 August at Dartington Great Hall, Devon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks