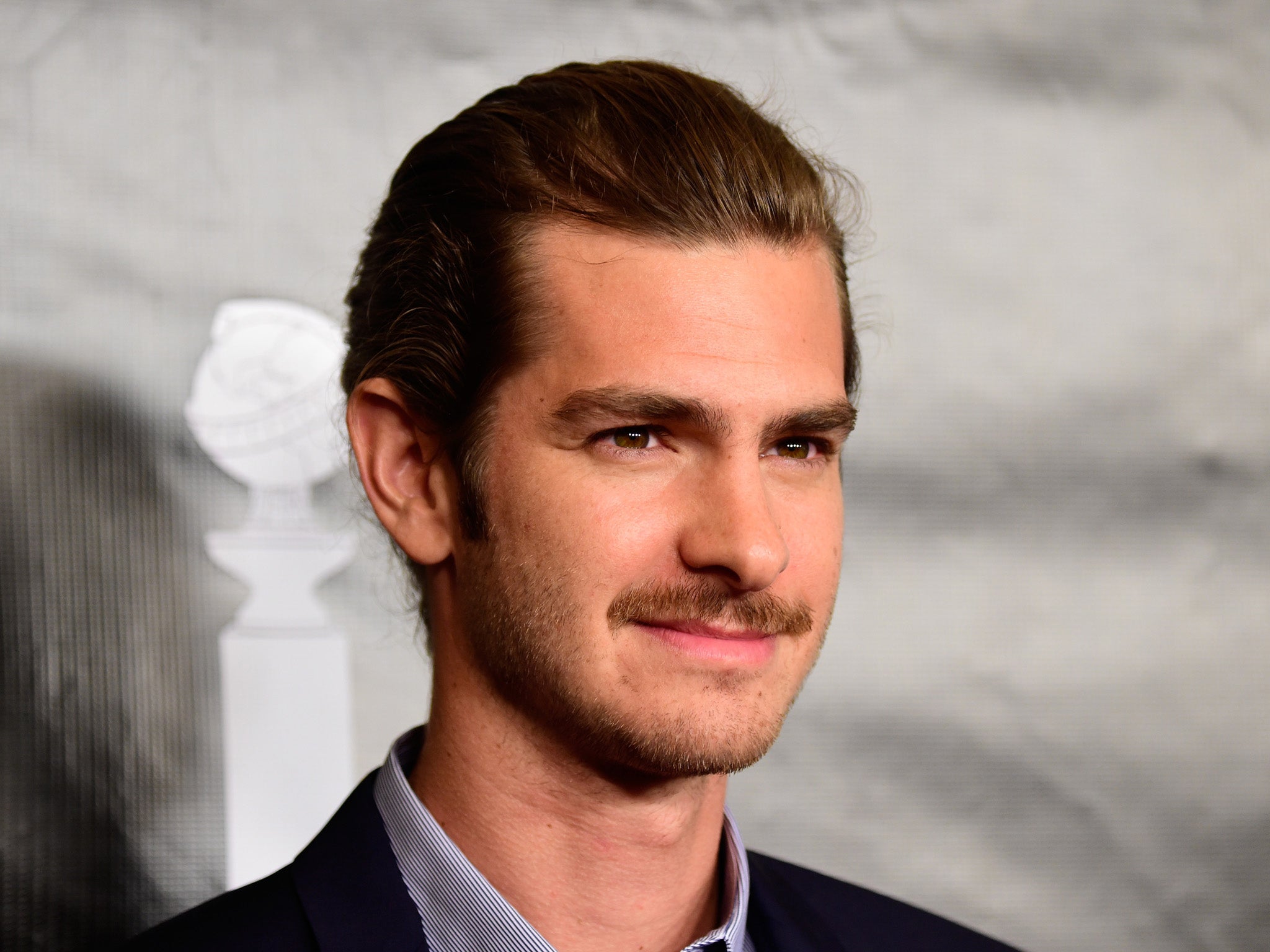

Andrew Garfield on The Amazing Spider-Man: 'I started to feel the separation of myself from the world - it hit me in a very sad, scary way'

Having escaped the superhero franchise, Garfield prepared for his new film '99 Homes' by carrying a gun and accompanying a repossession agent

With his easy laugh and relaxed demeanour, Andrew Garfield seems like a man who has received an early reprieve from a long sentence. He’s much too polite to put it quite like that, but he’s clearly relieved to be disentangled from the webs of the The Amazing Spider-Man franchise.

“There were beautiful things about it and also privileged things about it which I struggled with and then some really disenchanting things that happened,” says Garfield, 32, whose web-slinging days are officially over, the Spidey suit currently belonging to another British actor, Tom Holland, 19.

Back in 2010, fresh from his success with interesting roles as The Social Network’s Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin, and doomed Tommy in Never Let Me Go, Garfield was the new boy in town, the one to watch. But his anointing as the new Spider-Man quickly sent him spinning down the rabbit-hole of fame and all that entails.

“I started to feel the separation of myself from the world and from my community and it really hit me in a very sad and scary way, and I thought: ‘Oh f**k, I can’t live like this. I can’t be this thing that I’m being asked to be. Its just not real. If I chase that then I’m not being true to myself, and if I act as if I am somehow better, we all know that’s bullshit.’ I was really scared to be on some kind of forced pedestal. Thank god some people are smart enough to know the whole celebrity thing is a fallacy,” says the actor, whose relationship with Spider-man co-star Emma Stone was strained under constant paparazzi scrutiny.

Taking little comfort from the fact his two The Amazing Spider-Man movies grossed $1.5bn worldwide, he says: “Hollywood is the epicentre of worldly values where a piece of art is judged, not on how many lives it touches or what change it makes, but as long as that film makes money. Only then is it a success. Or as long as that film gets awards then it’s a success, its worthy to be here.” Not that he’s ungrateful.

“I feel lucky that I now have that awareness that something is damaging and can separate me from just being in the world, and I really want to be in the world even though it’s painful. I’d much rather be in the world than in some ivory tower somewhere.” Words to live by.

Previous Spider-Man press days would be two-day, stage-managed extravaganzas. Today when we meet at a Los Angeles hotel, there’s no security, no assistant sitting in on our chat. Just Garfield, stirring a cup of tea, his hair now brushing his shoulders, the beginnings of a beard sprouting from his chin. “I’ve enjoyed the long hair but it’s coming off any day now,” he smiles. He completed his second, and as it turns out last, Spider-Man outing two years ago, before stepping into the distinctly low-budget realm of Ramin Bahrani’s 99 Homes.

Tackling the US mortgage meltdown and foreclosure crisis through the framework of a thriller, 99 Homes is so real it often seems more like a documentary. Its Faustian themes resonated deeply with the actor, who would show up in Florida courtrooms, taking copious notes, as real-life families fought eviction notices, later meeting dozens of people whose lives had been devastated.

If it seems weird having a wealthy movie star show up at your door just when you’ve hit rock bottom, then he begs to differ: “If there was any of that, it was eradicated very quickly once they could feel I was actually there in compassion and love and empathy. We were really able to talk because I’ve also had experiences with this growing up in a family which was fearful of losing everything.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Born in Los Angeles to British mother Lynn and American father Richard, he was three years old when the family moved to the leafy suburb of Banstead, Surrey, where he and his elder brother attended private schools, both competing in local sports teams.

If it paints a picture of middle-class prosperity, then the truth was somewhat different. “We were under a lot of financial pressure when I was growing up,” reveals Garfield, whose role paved the way for he and his father to discuss their own versions of their shared family hardship. “It was a hot-button topic and we didn’t get to talk about it at the time because I was a kid and he was living it and not sleeping and trying to keep us afloat, and so was my mum. They were just trying to protect us and its a beautiful impulse,” says this son of a high-school swimming coach and nursery-teacher mother.

“So we got to really talk about that period of time and he got to reveal to me what that was actually like, and I got to reveal to him my own experience and how I knew what was going on even though no one was talking about it, and the atmosphere it created, in the house.”

The experience served him well for 99 Homes, in which he portrays unemployed carpenter Dennis Nash, who will do anything to keep a roof over his young son’s head.

Perhaps most surprising is Garfield’s revelation that he has never owned a home. “I don’t own anything, anywhere,” he says softly, appreciating he is anomaly in an elite culture where it’s a given that most movie stars own impressive property portfolios. “I don’t know what it is. I just haven’t felt like it’s been right yet.” He hasn’t even settled on a country to put down roots. “I haven’t moved anywhere. I’ve been around and about a lot.”

Overcoming early privations, Garfield followed his dreams, attending London’s Central School of Speech and Drama and launching a promising stage career, being acclaimed for performances in Kes and Romeo and Juliet. Subsequent roles in television’s Sugar Rush and Dr Who led to his US film debut, improbably co-starring with Meryl Streep and Robert Redford in political drama Lions for Lambs.

Despite all his success since, he relates passionately to 99 Homes’s themes of powerlessness and the plight of families who have lost everything, even serving as co-producer on the film.

“On a personal level, it was more about that feeling of being discarded, of being deemed unworthy or valueless, that hit me in a deep way.” It’s a feeling that has haunted him forever. “Since I was born I’ve had that feeling of: ‘Am I enough? Am I worthy? Am I supposed to be here?’ And my culture and society is telling me that I’m actually not in a lot of ways – unless I have this amount of money, or I’m in this kind of car and I have this kind of job, or I’m famous or whatever. Those are the things that our society values most right now, which is sick and a worship of false idols.”

Garfield is Jewish and chooses his words carefully when he compares prevailing trends to that of the Nazi regime. “It’s the same thing today that this story depicts – people just being discarded, deemed not of value – whether it be on a playground, or in a family situation where you’re a burden, or you feel unwelcome at the dinner table. Wherever it is, I think we all know that feeling of exile or not-enough-ness.

“I think about the Nazi regime and how direct that was; groups of people deemed unworthy of being alive. So Jews, gays, [the] disabled, [the] mentally ill – we’re going to take you into this place and we’re going to execute you, you will literally be evicted from life.

“There’s something insidious that’s happening in our culture, it’s unseen and slow and subliminal. Its the same message but its not mass murder, just slow, painful exile.”

For the role he accompanied a repossession agent, a “repo man”, knocking on doors and telling people to leave their homes.

“It was heartbreaking because he was heartbroken to be doing it. He’s a good man in a really horrible set of circumstances doing what he can to help with all the humanity he can muster. He was in a lot of pain for being in that position.”

In the US most repo men carry guns for protection, and Garfield holstered up for the role. “It was horrible. It’s so allergic isn’t it?” he says, referring to the peculiarly British unease that comes with living in a foreign country where guns are sold in supermarkets.

On bonding with the child actor who plays his son in 99 Homes, he says: “It caused me to ask questions about what does it truly mean to be a man in this modern age. There’s no context anymore for womanhood or manhood. The ritual of womanhood is a bit more firm because something physical happens but, as a man, there’s not some ritualistic thing that we get to do. The closest thing is sports, or enjoying the armed forces, which isn’t enough.”

Suggest that fatherhood changes a man, and he nods. “I think its inevitable but it doesn’t mean you are a man once you become a father.”

With Donald Trump’s presidential bid dominating the US news, images of Trump and his comb-over play on a TV screen in the background. “Donald Trump is a lost soul wandering this Earth,” he sighs. “He’s been led down the Willy Loman path and believes his own hype. He’s serving his little self and his little ego, otherwise why would he need to over-compensate so much?” The Loman reference comes readily to Garfield, who earned a Tony nomination for his performance as Biff in the 2012 Broadway revival of Death of a Salesman.

Taking some time out after completing 99 Homes, he travelled, regularly returning to Britain to visit friends and family. His parents’ house still feels like home to him, even though it has been many years since he lived there. “It has a lot of the old stuff. All of the meaningful, and some less meaningful, mementos of early life.”

At home, he always picks up The Independent. “I like reading The Independent because it’s a very impassioned newspaper that doesn’t sit on the fence with everything. What you guys do, from my understanding, is you come in with fire a lot of times, with true perspective and opinion.”

While searching for meaning in his post-superhero life, he received a call from Martin Scorsese, asking if he’d be interested in playing a Jesuit priest in the epic period drama based on Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel Silence. It was filmed on location in Taiwan, and he says of the experience: “I don’t know how that happened but I’m still in disbelief that I got to do it.”

‘99 Homes’ opens on 25 September, ‘Silence’ is scheduled for release in 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments