Blair Witch was a revelation, but found footage owes its roots to classic books

With shaky camerawork and creepy night-vision clips, we could feel the terror of our on-screen counterparts like never before in ‘The Blair Witch Project’. But, bringing a dose of faux reality into a fictional narrative can be traced back to the 1830s

At one point in 1999’s The Blair Witch Project, which tells the story of three young film-makers who head into the Maryland woods to make a documentary about a local legend, one of the trio, Josh, tells the lead Heather, “I see why you like this video camera so much.”

“You do?” she says.

“It’s not quite reality,” muses Josh. “It’s like a totally filtered reality. It’s like you can pretend everything’s not quite the way it is.”

Welcome to the cinematic sub-genre known as “found footage”, where – like Heather, who leads her friends into supernatural doom in the endless woods – we can pretend that everything we know might just be wrong.

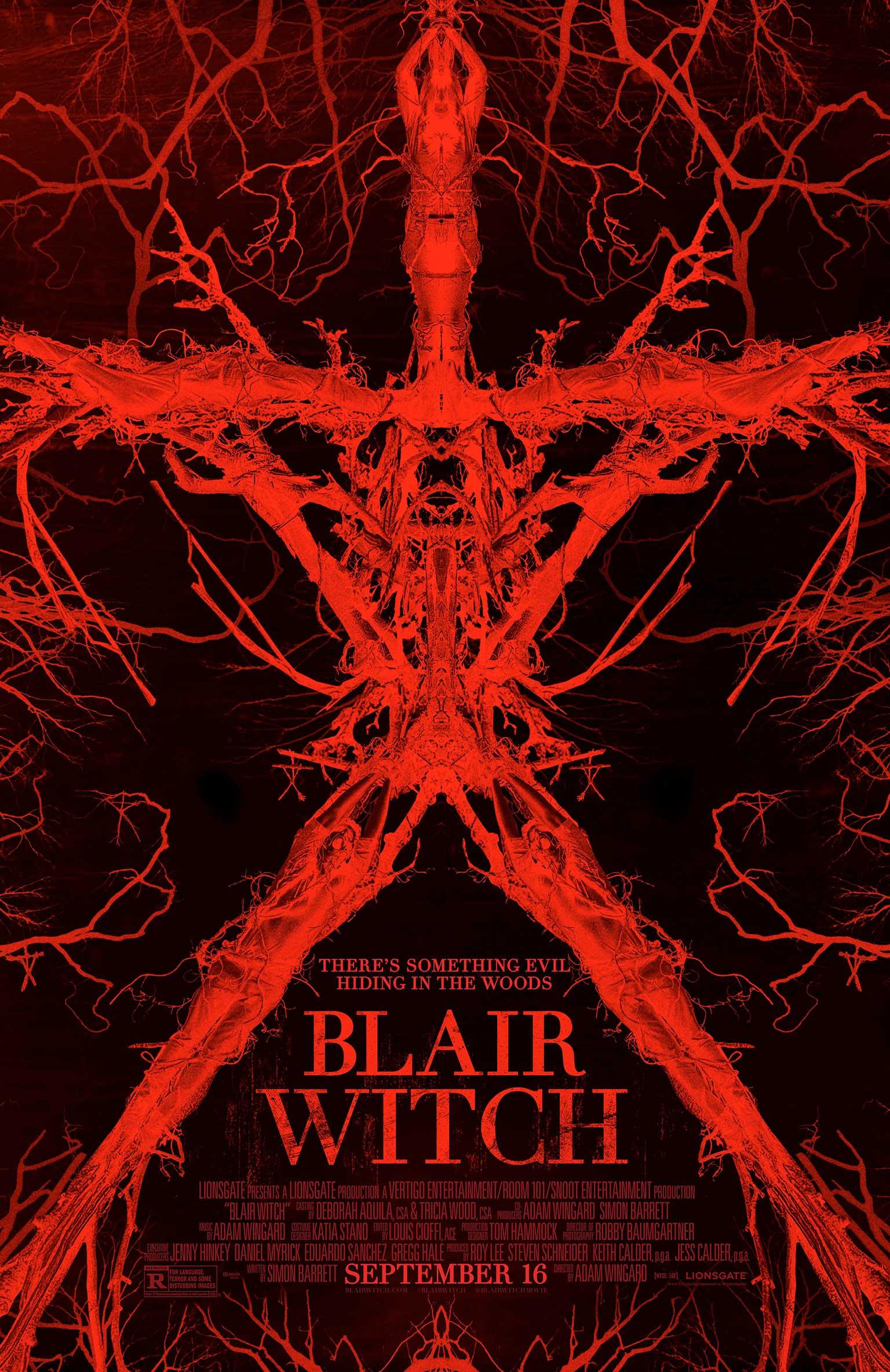

Found footage movies, like the original Blair Witch Project and like the much-anticipated sequel, Blair Witch, that goes on general release today, purport to be true stories assembled from discovered videos left behind after some mystery or horror. We know what we’re watching is fiction, we know it’s carefully constructed, but it’s not strictly the “reality” of normal drama, and for a couple of glorious hours we can imagine, as Josh said, that what we’re watching is not quite the fiction it is... and that it really, truly happened.

That’s the idea, anyway, and while the concept has been around for a while, it was The Blair Witch Project which popularised it in recent times and it’s hung around in one form or another ever since, with the format proving so popular that the long-awaited sequel pretty much re-uses the whole original story, with the sister of 1999’s Heather leading a group of college students into those cursed Maryland woods.

And, without second-guessing the movie, it’s not going to end well. Found footage films never do; that’s sort of the point of their central conceit: an investigation or expedition into something legendary or spooky goes awry, no-one comes home, and only their video evidence is left behind, to be pored over, edited and presented in documentary form for people to make up their own minds about.

The Blair Witch Project was groundbreaking and, more to the point, terrifying. Rather than watching from the detached safety of our living rooms, we found ourselves living through the terror with Heather, Josh and Mike; we shared their growing unease and jumped out of our skins at flashes of movement caught on night-vision. The shaky camerawork and close-up selfie shots exaggerated the sensation that this was the real deal, and that we were voyeurs, witnesses to something we couldn’t really understand.

As an aside, there was a similar found-footage movie out a year before the Blair Witch Project called The Last Broadcast, which followed a similar path into the New Jersey Pine Barrens. It didn’t garner much attention at first but earned itself a re-release post-Blair Witch, and is definitely worth a look.

But it was Blair Witch that set the standard and having done so, nothing really happened for another seven or eight years. Then there were a rash of found footage movies, including REC (2007), in which a reporter and cameraman trapped in a quarantined building record a zombie outbreak; Cloverfield (2008), JJ Abrams’ take on Godzilla, with a grotesque monster devastating New York caught on camera by a man tasked with videoing his friend’s leaving party, and Paranormal Activity (2007), featuring the footage shot by a couple trying to gather evidence of ghostly happenings. Dr Johnny Walker is a senior lecturer in media at Northumbria University and the editor of a book released this year on the urban myth of so-called “snuff” movies that were reputed to contain footage of real, on-screen murders (Snuff: Real Death and Screen Media). He says that it was the start of the Paranormal Activity franchise (it has spawned several sequels) that really fed the public appetite for found footage movies.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“In fact, it was around the release of that film that the term ‘found footage’ was first used as a name for the sub-genre,” he says. “The Paranormal Activity movies are very popular, both with audiences but also with filmmakers, because they are relatively cheap to make and extremely lucrative.”

But if The Blair Witch Project was so influential and effectively kick-started a sub-genre of horror movies, why the eight-year gap before the found footage form began to properly take hold, and the 17 years for a sequel to be made?

The answer, says Walker, is in the technology. Think back to 1999, and if you wanted to shoot even the most amateur film you had to buy a video camera costing several hundred pounds – and they were the ones that used videotape. “Digital video was something you didn’t see outside of European art film,” he says. “Now with smartphones everyone’s got a video camera in their pocket.”

Although The Blair Witch Project is considered the start of the trend, Walker points to one of the classic “video nasties” of the Eighties as the true beginnings of it – the infamous Cannibal Holocaust, a 1980 Italian exploitation movie which Walker describes as a “hybrid” – part found footage, part conventional movie framing – the “documentary” based on the film supposedly shot by an ill-fated expedition into the South American jungles.

But the concept of found footage goes back even further, before even the dawn of movies. As far back as the 1830s, the quintessential weird fiction writer Edgar Allan Poe was presenting ambitious stories that were suggestively titled as though to imply they were true accounts – see his 1833 short story MS. Found In A Bottle, about a sailor who falls in with a very strange crew, and his novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, which drifts on similar tides and upon its first publication in 1838 was printed without Poe’s name on the title page to suggest it was a true account written by the fictional Pym.

Even Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897, is composed of letters, reports and journal entries without any orthodox prose fiction at all, as though it were a collection of documents assembled to portray a horrifying narrative.

A century on, The Blair Witch Project brought that concept bang up to date and 17 years later, Blair Witch repackages it for the smartphone generation. Dr Walker will be going to see the new movie, but he does suspect that the found footage trend is on the wane.

“The market has become a little saturated recently,” he says, “and perhaps the two Blair Witch movies will book-end the trend, certainly for mainstream audiences. I imagine there will still be found footage movies made, but they’ll need to do something different and original to get such a high profile as Blair Witch.”

That said, as Dr Walker points out, we all carry around more video technology in our pockets than the amateur filmmaking crew had in their entire arsenal for the first Blair Witch movie. In other words, perhaps we’re all potentially a found footage horror story waiting to happen, which is something of a sobering thought.

‘Blair Witch’ is on general release from today

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks