‘We’re so scared of ourselves’: How a moral panic over video nasties swept the nation

Prano Bailey-Bond’s directorial debut rewinds to a recent past when minor horror films were demonised. As a veteran of 24-hour ‘video nasty’ festivals, which defied police action against tapes from the art-house slasher ‘The Driller Killer’ to ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’, Nick Hasted remembers the period intensely

It’s the 1980s, a moral panic about “video nasties” is gripping the nation, and troubled film censor Enid (Niamh Algar) is guiltily slipping into a backstreet video store for a drop of the hard stuff: an uncut, under-the-counter tape by a mysterious horror auteur whose work is warping her dreams. Soon her waking, professional world is in meltdown too, as she uncovers the sunken trauma of a missing sister. Oddly, by the time an enemy’s face is gorily skewered, turning her own life into a video nasty, Enid is starting to feel a whole lot better.

Prano Bailey-Bond’s directorial debut Censor rewinds to a recent past when minor horror films were demonised as existential threats to British life. It reconfigures this Thatcherite culture war so that, for Enid, experiencing such films’ extremes becomes a strange act of healing. “I’m drawn to horror to explore repression of things we don’t want to address,” Bailey-Bond considers, “and the way those things will eventually seep out. The more you try to fight it, the more twisted it becomes. That is what Enid’s going through. And censorship embodies that in so many ways, because it is saying: ‘We can’t look at this stuff, because it’s going to corrupt us, and doesn’t belong in the world.’”

Censor is an oblique take on the “nasties” phenomenon, dealing in psychology and metaphor, not historical verité. The reality, though, is equally outlandish. Much like the reaction to videogames and social media in the years since, it was rooted in dismay at the anarchy of a new, unregulated medium, as video stores opportunistically sprang up on every street corner. Films denied certificates by the British Board of Film Censors (now Film Classification) – the BBFC – such as Tobe Hooper’s gruelling The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), soon found their way into unsuspecting homes.

The era’s iconic, if much parodied, anti-“smut” campaigner Mary Whitehouse probably coined the term “video nasties” in 1982, with The Sun taking up the phrase that year. An informal “long list” of video nasties was drawn up by the director of public prosecutions, as cine-illiterate police rounded up random tapes including Apocalypse Now and Midnight Express. Mary Whitehouse seized her moment, compiling extreme “nasty” scenes for screening at 1983’s pre-election Tory conference, then again in parliament. “You could say that the films were taken out of context, but… so what?”, Whitehouse’s deputy John Bayer told me when I questioned the deceptive use of this footage in 1987. “Even you couldn’t deny [their] general loathsomeness.”

Seeking to exploit the panic for the purposes of their wider law-and-order agenda, the Tories’ manifesto associated “the dangerous spread of violent and obscene video cassettes” with “serious crime”, promising a Video Recording Act that would require videos to be certified by the BBFC. Its passage through parliament in 1984 was accompanied by assertions more frenzied than the films. “No one has the right to be upset at a brutal sex crime or a sadistic attack on a child or mindless thuggery on a pensioner,” Home Office minister David Mellor shamelessly warned, “if he is not prepared to drive sadistic videos out of high streets.”

“A couple of things really fascinate me, looking back,” says Bailey-Bond, who, born in 1982, sees the panic retrospectively. “There’s always this fear of new technology, and the way it’s going to make us think and behave. I’m interested in why we’re so scared of ourselves: that we think that deep down humans are immoral, and waiting to have that awoken by a technology that will make us kill each other. And I see an easy scapegoat for all the bad things that are happening in society, which perhaps were caused by a government who were not treating society well.”

The fightback against the video purge was ironically left to the cinema screen. The notorious, much-lamented Scala cinema, in London’s then-seedy King’s Cross, used its status as a cinema club, and the fact that numerous banned videos held cinema certificates, to run all-day, all-night festivals compiled from the “nasties” long list, pointedly allowing these demonised works to be viewed in full.

“You could oddly see these films in cinemas,” recalls Jane Giles, a Scala habitué who became the cinema’s programmer from 1988 to 1992. “So from December 1983 through most of 1984, JoAnne Sellar was programming those films in order to draw attention to the Video Recording Act as it ticked through parliament. It was provocative – one bill was called Sliver Bright’s Liver, after Graham Bright, the MP who had sponsored the bill. JoAnne invited all the MPs who were voting on it, because you need to see this material to make up your minds. JoAnne was 19 or 20 at the time. It’s been forgotten that there were these really punky young women, who were campaigning for the freedom to see wild movies.”

“It wasn’t snickering boys with plastic bags under the counter,” she says of the desire to watch a film such as Cannibal Holocaust (1980), with its rumours of real, “snuff film” slaughter. “That’s what people were forced into. But actually, we would like to see this material to understand what it is.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

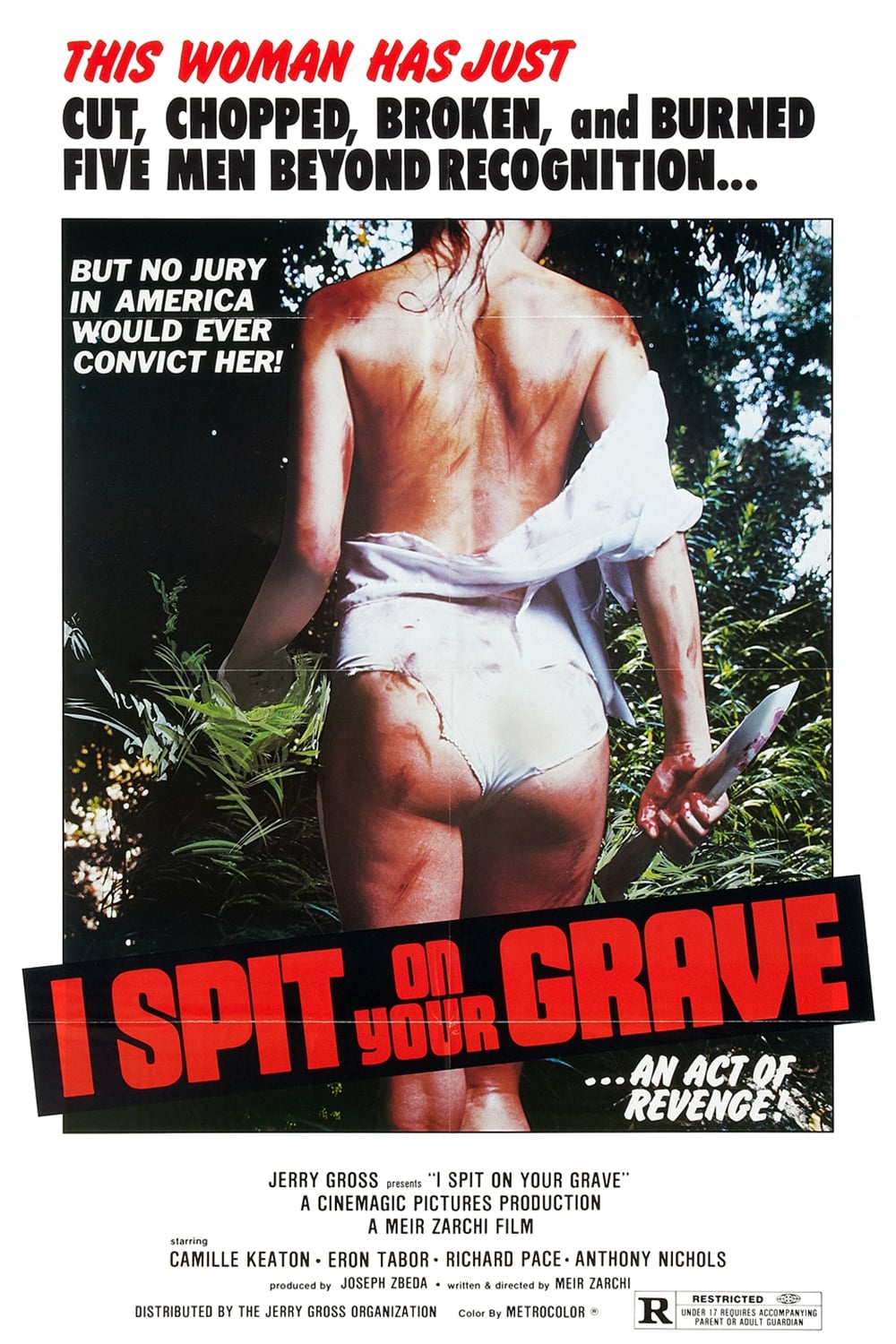

I attended a couple of those bills as a teenager travelling in from the Essex suburbs, and the “nasty” aura was stripped away on full contact with the real thing. Abel Ferrara’s The Driller Killer (1979) was revealed as a grungy portrait of a downtown Manhattan painter (played by the director) driven by city psychosis to fatally wield a power tool, a mix of proto-Jarmusch, Jackson Pollock and Jeffrey Dahmer, giving fair warning of later Ferrara classics such as Bad Lieutenant (1992). Future Spider-Man director Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1981) was grisly, gory slapstick, while I Spit on Your Grave (1978), was built around a still-divisive rape-revenge template. (It was, in fact, recently rebooted as a relatively respectable feminist franchise.)

That was educational. But what was more memorable was the dreamy drift as The Exorcist flickered through my consciousness in the small hours, making more sense than it ever has since, before I arrived back home in Sunday morning sunlight. One of the Video Recording Act’s least intended consequences was to create something very like a horror rave.

“If you weren’t on speed to keep you awake,” Giles agrees, “you would get this very strange experience of your dreams mingling with what you saw, or what you thought you saw. Also the Scala was an exceptionally atmospheric cinema. There was a real sense of occasion and anticipation, making the all-nighter a physically, emotionally and psychologically challenging rite of passage. And because it was pre-internet, you weren’t so prepared for what you were going to see. Then I’d wake up and go into King’s Cross first thing in the morning like a zombie. It was a great experience.”

If any film captures that time’s fever, it’s David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), in which a feral, wired James Woods receives a seemingly sadomasochistic snuff video that seems just right for his cable TV channel – until, that is, the TV screen bulges, and a vaginal slit in his stomach viscerally replicates the video player’s portal, as video and real life merge in queasy hallucination. Cronenberg began, he told Cinefantastique, with “the idea of people locking themselves in a room and turning a key on a television set so that they can watch something extremely dark, and … allow themselves to explore their fascinations”.

Much like Cronenberg, Censor, though shot on film, explores video as a medium. The owner of the shop Enid visits warns her that “they’ve taped over the ending with another film”, and “the good bits have gone a bit fuzzy”, suggesting video’s novel sense of agency. Once you brought a tape home, you could do what you wanted.

“When you talk to censors of the period,” Bailey-Bond notes, “people were afraid of this idea that people could take control of their own viewing, and rewind and study things. Then you talk to horror fans, and they’d rewatch the gory bits, and found those moments got snowy, as that bit of tape was scratched and worn down, and that in turn signified a scary bit coming up. Everything’s so clean now, but I like things to look and feel grubby sometimes! VHS suited the video nasties, because they were grubby, a lot of them.”

“There was a fuss at the time about ‘innocent children’ accidentally seeing this material,” Giles adds, referring to a perceived peril that formed a central tenet of the Video Recording Act. “Home was supposedly this sacred environment that this vile material should not be allowed to contaminate, a conservative ideal personified by Mary Whitehouse. Actually, home has always been a place that was full of risk for children, women, and vulnerable adults.”

Interviewing female BBFC censors who’d worked through this period, Bailey-Bond heard diverse views of the job that makes Enid unravel. “I spoke to one who wasn’t a big fan of horror,” she says, “and [who] found working in the offices very oppressive. She said she’d be in a dark, windowless room all day, uncomfortably watching what sometimes felt like soft porn. And then she’d leave work and it’d be night-time, so she felt she was existing in darkness. She said it made her feel vulnerable, during this period. Whereas I spoke to another female censor who said she was a big fan of horror. She was also a psychotherapist, and felt that horror was very important. She was very focused on violence towards women in these films. But she never felt vulnerable or afraid watching them.”

“I saw Censor last week,” Giles says. “It wasn’t quite the 1980s that I remembered. And the story Prano has created, of a censor and what she’s censoring from herself, is completely different to my story from that time, which is of the 19-year-old JoAnne Sellar, campaigning.” Then again, she adds, “what’s different from back in the Eighties is now we have women making horror films. So good for Prano.”

‘Censor’ is in cinemas now. Jane Giles’s book ‘Scala Cinema 1978-1993’ is published by FAB Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks