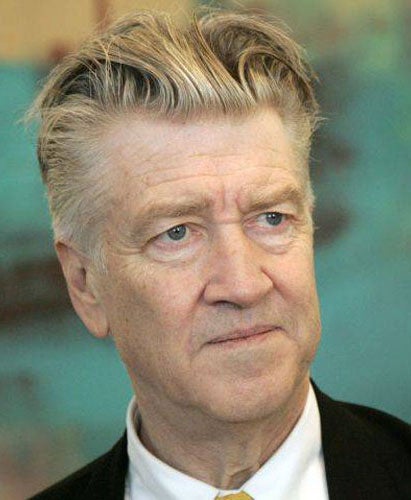

David Lynch: 'They murdered my first movie'

Today, his films are considered cinematic masterworks – yet David Lynch is still smarting from criticism of his debut, Eraserhead. On the eve of its re-release, the director talks to Sophie Morris

No one in Hollywood is shy of self-promotion. David Lynch, though – despite being the man who led a cow through town to advertise his last film – is the person one would least expect to put his name and face to a range of merchandise. Yet, at mid-morning in his Los Angeles office, he is supping his own-brand organic espresso, the David Lynch Signature Cup, which you can buy from his website.

It took Lynch around 18 months to find a blend of coffee he was happy to put his name to, quite a conservative commitment given the many years spent patiently chiselling away at some of his films. The coffee is, he says, "exceptionally good". If he reached the ideal blend via the same methodical, perfectionist workmanship with which he executes his films, it no doubt is.

Lynch's movies are, notoriously, as oblique as they are opaque, but it is possible to trace a style of sorts through his oeuvre. He searches out the details most overlook in America's metropolises and in its misleadingly quiet small towns, and abandons the rigours of linear narrative and traditional characterisation in favour of a sheaf of repetitive themes and ticks, and a reflexive strumming on the limitless realm of the subconscious. Acting, Hollywood and film-making also feature frequently. Rather than write around a story, Lynch seems to collect a huge number of complex images, magpie-like, which he then pieces together into a film. He began as a painter and switched to film when he saw a garden he had painted moving on its canvas, and has since introduced generations of film-goers to an experience where image takes precedence over narrative, and identity is fluid.

Even within Lynchian convention he is wont to surprise. Take just the last decade of the 30 years since his feature debut, Eraserhead. In 1997 came Lost Highway, a confusing noir and pure Lynch, which probably won him as many new admirers as Eraserhead and Blue Velvet had in the 1970s and 80s. To follow this with the endearing simplicity of the Disney-financed The Straight Story (1999) was a masterstroke, generating as much buzz for its apparently guileless storytelling as any of his more disturbing offerings. It is a sympathetically observed road movie, which gave the impression Lynch was going rather soft in his late middle age. In fact he only came on board to direct after the script had been written, by his then partner.

Then came Mulholland Drive (2001), the dreamy blockbuster set on the periphery of Hollywood, amid the seedier of the film world's sub-industries. Dazzling, mysterious and dark in equal parts, it won Lynch a best-director award at Cannes and an Oscar nomination.

Critics were still battling to tether Mulholland Drive to some meaning when he stunned them five years later with Inland Empire, starring Laura Dern, one of his favourite leading ladies. Its plot is so unintelligible that it is quite a struggle to watch. You get the feeling that Lynch skipped school the day the teacher explained why all stories should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but cinema would be a much drier place had he attended that class. "Everything has a structure," he protests. "Sometimes they are more straight-ahead than others. I understand Inland Empire is maybe more abstract than the rest."

He is reluctant to talk about his private life or his films, which suggests interviewing him would be a frustrating process. But again he subverts expectation and is so charming, attentive, and avuncular that it is easy to forget this is the man who created such cinematic monsters as Mystery Man in Inland Empire or Twin Peaks'sBob.

It is not that he won't talk about his films – in fact he has documented much of his filmic practice in two books, Lynch on Lynch and Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. He held forth on the latter during his tour of the UK and Ireland, with the musician Donovan, last autumn. (It was to raise money for the David Lynch Foundation, which funds transcendental meditation as an educational tool.) It is specifics he refuses to be drawn on. Does he make films for a particular audience? "No". Who are his favourite characters out of the many he has written? "I love all the characters. I just love 'em." Where did you get the ideas for Mulholland Drive? "I knew it was about a girl who wanted to be an actress coming to Los Angeles and I knew the title."

Lynch's inspirations include Fellini, Kubrick, Hitchcock, Bergman and Tati, but his ideas, he always says, just come to him – when he's meditating, in dreams, maybe over breakfast. This is because the real Lynch slips between his own conscious and subconscious as readily as his films do, during his rigorous twice-daily practice of transcendental meditation. He hasn't missed a day in 35 years. The ideas plucked from his subconscious are then worked at until rendered exactly as he saw them. They must be just so. All this sounds painstakingly arduous, but Lynch does not suffer for his art; he revels in it.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

"I love to translate ideas," he says. "If you are true to the ideas that you love and never walk away from any element until it's correct, then there's a chance others will feel it's correct and go into that world and have an experience. Hopefully a good experience."

The fact that his first feature, a film-school-funded project which took five years to complete, is being reissued 30 years after it came out proves that plenty of people consider his films a "good experience".

Eraserhead is one of those films you might think brilliant, but is far from an enjoyable watch. Lynch is very pleased with the digital remastering (it has been available in the US since 2000). "It's very clean and pure," he says. Does he wish he had done anything differently? He was delivering papers to raise the money to get it made, so he must have made certain sacrifices.

"It's next door to a perfect film," he pauses, before a low chuckle. For all the weight of his subject matter, Lynch has a wonderful sense of humour – revealed on screen in his Twin Peaks cameo as Gordon Cole, the deaf FBI agent – and spot-on comic timing. He then insists: "It really was close to exactly what I wanted to make. I loved the world of Eraserhead. I can revisit that world by watching the film now."

He recently did just that, with his 16-year-old son. The Philadelphia depicted in grimy monochrome in Eraserhead is a city full of shadows of people, most of them terrifyingly bonkers with – perhaps – the exception of the bewildered lead, Henry Spencer. Lynch will only offer one judgement of the film, describing it as "a dream of dark and troubling things", though he admits that its gothic maelstrom was inspired by his own time in Philadelphia between 1965 and 1970.

"It is known as the city of brotherly love," he explains, "and it's the furthest from a city of brotherly love. There is tremendous corruption, violence, fear, sickness in the atmosphere in Philadelphia. But it was an ideas factory for me. I loved and hated being there. I never wanted to go there, but there I was."

And it was there he created Spencer's sickening, slimy, premature baby, with a bandaged stump for a body and a putrefying head like a skinned squirrel's, perhaps the most unsettling invention in modern cinema.

The only negative comment Lynch utters throughout the entire interview is to condemn the reviewers who "murdered" Eraserhead when it first came out. "The mainstream critics just trashed it like Neanderthals," he says. He followed it up with The Elephant Man in 1980, which earned him eight Oscar nominations, and Blue Velvet (1986), a controversial but mainstream success which led to a five-year relationship with its star, Isabella Rossellini. Between them came Dune, a bungled sci-fi and the only film he regrets making.

It is transcendental meditation, not film-making, upon which Lynch is happy to evangelise, though the one stokes the other.

"Everybody has consciousness," he says, "but not everybody has the same amount. If you want to get more, you just learn the technique to dive within and experience the deepest level of life. Then you can catch ideas on a deeper level and appreciation of everything grows. It's a very beautiful process for the artist and for the human being."

His foundation funds transcendental meditation in some of the worst schools in the US, so the students and teachers can benefit from its stress-busting and creativity-enhancing properties. "It works! ," he says. "These schools are filled with bliss. Relationships improve. Grades are going up. It's a beautiful thing."

His love for meditation earns Lynch the "wacko", "weirdo" and "nutcake" tags as much as his films do, but for a man so obviously at one with the world, however troubling and bizarre that world may be, it clearly makes sense. His British followers, though, have their minds on rather more pressing, Earthly matters right now, such as when – if ever – we will get the second season of Twin Peaks on DVD.

'Eraserhead' will be re-released at selected UK cinemas tomorrow, and on DVD on 20 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks